On the Shangri-la diet forums, many dieters have reported better sleep. (”Woke up feeling like I could fight tigers. Have not felt this way since 2003. . . . I would stay on this method just for the sleep benefits,” wrote bekel.) To learn how widespread this was, I did a poll. Forty-two people answered. Two-thirds of them reported better sleep (half “much better” sleep, half “slightly better” sleep). Only one-tenth of them reported worse sleep (all “slightly worse”, none “much worse”). Almost all of them were doing SLD with oil, implying that the improvement was due to a few tablespoons of oil per day.

This was exciting. A small, almost trivial dietary change seemed to be causing a big important improvement. I had switched from sugar water to ELOO about three years ago and had not noticed any sleep improvement. Perhaps this was because the improvement is due to omega-3 fatty acids, of which ELOO has much less than other oils. And because I ate a few servings of fatty fish (such as salmon) per week, I might have been less omega-3 deficient than most. Thinking about the poll results, I remembered I had slept unusually well about a week or so earlier. At roughly the same time, for reasons I can’t remember, I had taken six or seven flax-oil capsules. This vague correlation was curious. It raised the possibility that a large dose of omega-3’s might have a noticeable effect.

To test this idea, I made two changes: (a) I started drinking 2 tablespoons/day of walnut oil. Walnut oil (12% omega-3) is a much better source than olive oil (1%) or canola oil (7%). (b) I started taking 10 flax-oil capsules/day (= 100 calories/day). Flax oil (58% omega-3) is an especially good source. (I drank Spectrum refined walnut oil, which has little flavor, and I mixed it with water to reduce its flavor. Another walnut oil I have tried, International Collection, has a strong walnut flavor.)

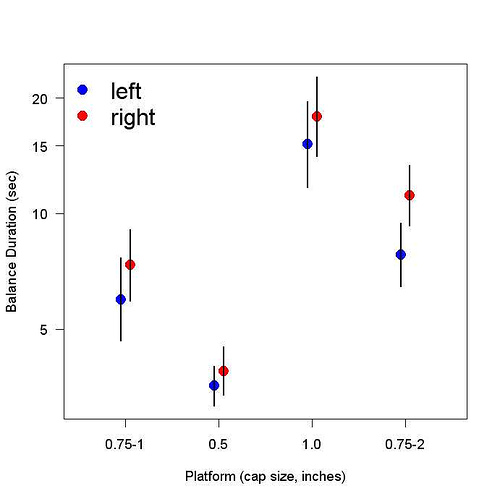

It seems to make a difference. Three differences, actually: (a) Better sleep. I wake up more clear-headed, less foggy. (b) Better mood. My overall mood is slightly better, in a hard-to-describe way. (c) Better balance. For the last two years, I have often put on and taken off my shoe-laced shoes while standing; even after two years of practice there was plenty of room for improvement. Suddenly this became much easier. All three changes began the day after the dietary change (about a week ago) and since then have not only persisted but if anything have gotten stronger.

Do these bits of data — survey and self-experimentation — mean anything? I think so. Consider other facts:

1. SLD dieters using oil report many other improvements that seem unrelated to less hunger or weight loss. Most of them fall into three groups: (a) Skin. Everyone reports softer skin. In addition, spacehoppa’s eczema and keratosis pilaris (permanent gooseflesh) got much better “It’s like I’m correcting a major nutritional deficiency,” she wrote. Shrinkingbean found her eczema improved after only 10 days. CarolS’s acne has gotten much better. (2) Mood. Easier to give up smoking and coffee. More libido. (3) Stiffness. “I have been a person who gets stiff when sitting too long, ever since I was in high school. . . . Sitting in one place for 15 minutes would cause me to stand up from the chair like a 90 year old. . . . It just dawned on me that that is no longer true!!!!” wrote Ann. Two others noticed similar effects.

2. Several studies of patients with mood disorders have found their symptoms improved when they were given fish oil (high in omega-3) compared to a placebo group. A review of these and similar studies notes that “the marine-based omega-3 fatty acids primarily consist of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and appear to be highly biologically active. In contrast, those from plants (flaxseed, walnuts, and canola oil) are usually in the form of the parent omega-3 fatty acid, alpha-linolenic acid. Although dietary alpha-linolenic acid can be endogenously converted to EPA and DHA . . . research suggests that this occurs inefficiently to only 10%-15%.”

3. Several surveys of the elderly have found an association between (a) reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease and less cognitive decline and (b) greater fish consumption. At the other end of life, omega-3 fatty acids are necessary for proper development of our brains, a point made here. The effect of an essential nutrient is likely to be clearest in those who are most vulnerable (such as babies, the elderly, and the mentally ill).

What makes the overall idea — we need more omega-3 than most of us get — even more plausible is that a pre-existing theory makes sense of these facts. That theory is the aquatic-ape hypothesis, the idea that humans became big-brained primates while living near water and eating lots of fish. In 2005, Sir David Attenborough, whose nature documentaries I love, made a fascinating radio show about this theory. The end of the show provides new supporting data that I find especially persuasive.

If our brains grew big while eating lots of fish, it makes perfect sense that they would work better when we eat lots of fish. More precisely, too little fish (or too little of fish’s crucial nutrients) should harm the portions of our body that evolved during that period (shaped to work well on a high-fish diet) much more than older portions (shaped to work well on a low-fish diet). The improvements associated with omega-3 fatty acids — reduction of cognitive decline in the elderly, mood improvements in the mentally ill — fit that prediction well. So does the conclusion of a recent meta-analysis that omega-3 does not clearly reduce heart disease or cancer.

And so do the benefits of oil (presumably from omega-3) suggested by the SLD forums and my self-experimentation. Sleep: My earlier self-experimentation suggested that sleep is influenced by morning conversations and amount of standing, implying considerable differences between our sleep and the sleep of other primates. Skin: Human skin has fat attached, like marine mammals but unlike the skin of other primates. (This fact inspired Alistar Hardy to think of the aquatic ape hypothesis.) In addition, we have much less hair than other primates. Stiffness when standing up and balance on one foot: Unlike other primates, we are bipedal.

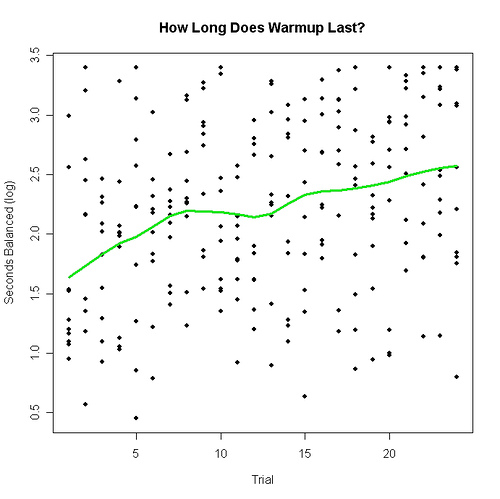

How to measure my sense of balance? . . .