In the Freakonomics blog, Ian Ayres, a Yale law professor, described a Law Revue skit at his school:

A group of students [were] sitting at desks, facing the audience, listening to a professor drone on. All of the students were looking at laptops except for one, who had a deck of cards and was playing solitaire. The professor was outraged and demanded that the student explain why she was playing cards. . . . She answered, “My laptop is broken.”

Not bad. The professors in the audience were stunned.

The skit was “several years ago.” I wondered how Ayres would manage to connect revelation of a timeless truth about higher education (see For Whom Do Colleges Exist?) with something new. Here’s how:

Saul Levmore, the dean at the University of Chicago Law School, has recently announced an end to classroom surfing.

The big truth behind the little joke was . . . hard to see. Or at least hard for professors to see. The big truth is that law schools, like most institutions of higher education, are run in dozens of ways that benefit professors at the expense of students. Boring lectures are one example. In response to a small revelation of this big truth, Dean Levmore — presumably after consultation with many other law school professors — created another example of how law schools are run for professors rather than students.

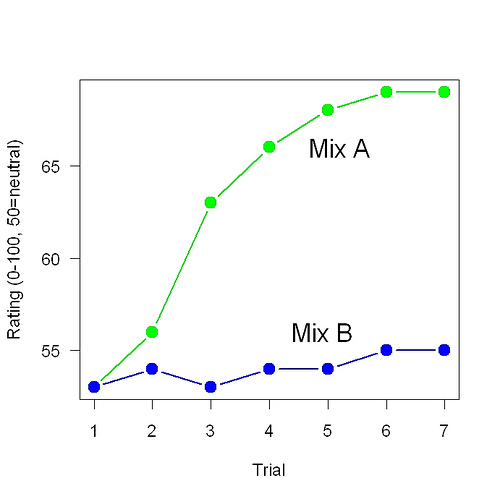

Difficulty with basic concepts at Duke and UC Berkeley.

More. I suppose solitaire is still okay at the University of Chicago since it doesn’t involve surfing.