Yesterday I went to San Francisco early in the morning. Because of my discovery about standing and sleep, I had slept very well. In Berkeley, it looked like morning: empty streets, angle of light. I felt jet-lagged: I should have been tired but I wasn’t. On BART, the same mismatch: Everyone looked tired but I was wide awake.

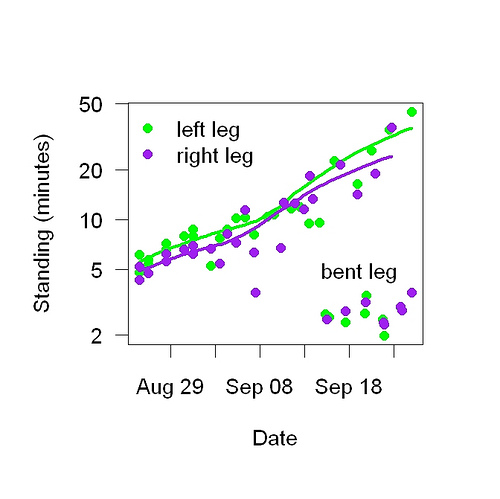

It is taking longer and longer to get enough one-legged standing to generate great sleep. Here’s a graph of how long I’ve been standing: Each point is a different bout of one-legged standing. Most of the points are from bouts where the standing leg was straight or bent (usually straight) but a few of them (“bent leg”) are from bouts where the standing leg was bent the whole time. Most days have two bouts: 1. On the left leg until I get tired. 2. On the right leg until i get tired. I’m pretty sure there’s no effect until it becomes difficult — until the muscles are so stressed that they send out a grow signal. The whole thing is pleasant because I watch TV or a movie at the same time but, as the graph shows, it has become seriously time-consuming.

Each point is a different bout of one-legged standing. Most of the points are from bouts where the standing leg was straight or bent (usually straight) but a few of them (“bent leg”) are from bouts where the standing leg was bent the whole time. Most days have two bouts: 1. On the left leg until I get tired. 2. On the right leg until i get tired. I’m pretty sure there’s no effect until it becomes difficult — until the muscles are so stressed that they send out a grow signal. The whole thing is pleasant because I watch TV or a movie at the same time but, as the graph shows, it has become seriously time-consuming.

So I have tested keeping the standing leg always bent. I get tired much sooner (2 minutes versus 20 minutes) but the effect is not quite as strong. Probably because fewer muscles are involved — you use more muscles when you stand on one leg in any possible way than if you stand on one leg in only one way.

I assume there’s a steady-state solution. The more muscle you have the more you lose each day. (Just as the theory behind the Shangri-La Diet assumes that the higher your set point, the fast it falls.) Eventually I should have enough muscle and will lose enough in one day so the exercise needed to merely replenish it will be enough to produce great sleep.

Seth – have you considered adding weight? Apologies if you have discussed this earlier in the series. Seems like a good way to keep it simple but also keep the time down. A good quality weighted vest might do the job…

You can also do one legged squats once your legs get strong enough.

A full range squat is going to work a lot of the muscles in your leg (vs. a partial).

You can start with just bodyweight squats, all the way down and up, you don’t need to use weight, but eventually switch to single leg squats when you are strong enough.

That should get the time down to a much shorter time. Even a hundred body weight squats can be done in a couple-three minutes, and that is a large number.

Methuselah & Stephen, thanks for the suggestions. Funny, I just threw away an old backpack…which I have now retrieved from the trash.

Once you’re in good enough shape, two-minute one-armed handstands ought to suffice for quite a while. When you get to the point of tongue-stands, I think you’ll need to think of something else.

Maybe adding a balance challenge to the one-bent-leg technique would make it more effective. Balance engages a whole host of additional supportive muscles, which may partially account for the original value of this technique (and why it hasn’t been reported from more common leg exercises).

So perhaps try doing the bent-leg on some kind of wobble-board, being careful to ensure you’re safe. Fitness centers sell variations of these devices, they are inexpensive, and balance is a great fitness element to work on anyway. Or a higher level challenge might be to try juggling. The cerebellum controls this type of coordination, and there is evidence of abnormalities in the cerebellum in dyslexia. Some researchers have claimed that very demanding physical challenges (hand-eye coordination at the same time as balancing, for instance) can ameliorate some symptoms of dyslexia, presumably by enhancing the function of this part of the brain.

Then add the one-armed handstand.

that’s an interesting graph you have there.