Inspired by Andrew Gelman’s posting of his discussion of a paper, here is a review I recently wrote of a omega-3 epidemiology paper. The shortcomings — or opportunities for improvement — I point out are so common that I hope this will be of interest to others besides the authors and the editor.

This is an important paper that should be published when the analysis is improved. The data set analyzed was gathered at great cost. The question of the relationship between omega-3 and *** [*** = a health measure] is very important and everyone would like to know what this data set has to say about it.

That said, the data analysis has many problems [= opportunities for improvement]. Most of them, perhaps all of them, are very common in epidemiology papers, I realize. Here are the big problems:

1. No figures. The authors should illustrate their main points with figures. They should use lowess — not straight lines — to summarize scatterplots. The relationships are unlikely to be linear.

2. Failure to transform their measures. Every one of their continuous variables should be transformed to be roughly normal or at least symmetrical before further analysis is done. It’s very likely that this will get rid of the outliers that led them to treat a continuous variable (omega-3 consumption) as a categorical one.

3. What was the distribution of *** scores? How did this distribution vary across subgroups? If the distribution isn’t normal — and it probably is far from normal — then a transformation might greatly improve the sensitivity of the analysis. Since the distribution is not shown the reader has no idea how much sensitivity was lost by failure to transform.

4. Pointless analyses. It is never explained why they separately analyse EPA and DHA; that is, no data are given to suggest that these two forms of omega-3 have different effects. Rather than analyse separately EPA and DHA they should simply analyze the sum. Nor is there any reason to think that fish consumption per se — apart from its omega-3 content — does anything. (At least I don’t know of any reason and this paper doesn’t give any reason.) Doing weak tests (fish, EPA alone, DHA alone) dilutes the power of the strongest test (EPA + DHA).

5. Failure to test the claim of interaction. I don’t mind separate analyses of large subgroups but if you say an effect is present in women but not men — which naive readers will take to mean that men and women respond differently — you should at least do an interaction test and tell readers the result. (You should also provide a graph showing the difference.) Likewise if you are going to claim Caucasians and African-Americans are different, you should do an interaction test. Perhaps the results are different for men and women because *** — and if so there may not be an interaction. Finding the relationship in women but not men has several possible explanations, only one of which is a difference in the function relating omega-3 intake to ***. For example, men might have more noise in their omega-3 measurement, or a smaller range of omega-3 intake, or a smaller range of ***, and so on. The abstract states “the associations were more pronounced in Caucasian women.” The same point: When the authors state that something is “more” than something else, they should provide statistical evidence for that — i.e., that it is reliably more.

6. It is unclear if the p values are one-tailed or two-tailed. They should be one-tailed.

7. It is unclear why the data are broken down by race. Why do the authors think that race is likely to affect the results? Nowhere is this explained. Why not stratify the results by age or education or a dozen other variables?

8. The authors have collected a rich data set — measuring many variables, not just sex and race — but they inexplicably do a very simple analysis. If I were analyzing these data I would ask 2 questions: 1. Is there a relation between EPA+DHA and ***? This is the question of most interest, of course, and should be answered in a simple way. This is a confirmatory analysis. 2. Getting some measure of that relationship, such as a slope, I would ask how that slope or whatever is affected by the many other variables they measured, such as age and so on. This is an exploratory analysis. There are no indications in this paper that the authors understand the value of exploratory analyses (which is to generate new ideas). Yet this is a good data set for such analyses. To fail to do such analyses and report the results, positive or negative, is to throw away a lot of the value in this data set.

9. The single biggest flaw (or to be more positive, opportunity for improvement) is losing most of the info in the *** measurements by dichotimizing them . . . .

It would also be nice if epidemiologists would stop including those “limitations” comments at the end of most papers. They rarely say something that isn’t obvious.

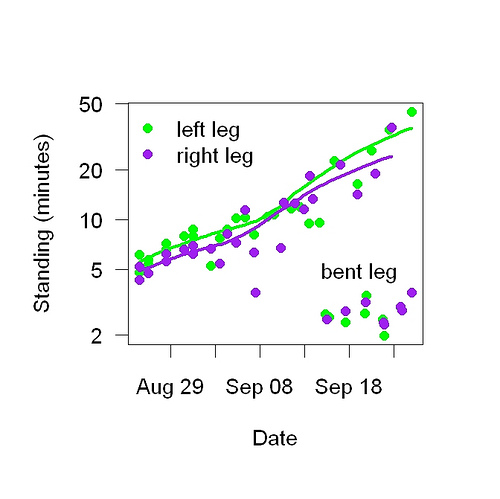

Each point is a different bout of one-legged standing. Most of the points are from bouts where the standing leg was straight or bent (usually straight) but a few of them (“bent leg”) are from bouts where the standing leg was bent the whole time. Most days have two bouts: 1. On the left leg until I get tired. 2. On the right leg until i get tired. I’m pretty sure there’s no effect until it becomes difficult — until the muscles are so stressed that they send out a grow signal. The whole thing is pleasant because I watch TV or a movie at the same time but, as the graph shows, it has become seriously time-consuming.

Each point is a different bout of one-legged standing. Most of the points are from bouts where the standing leg was straight or bent (usually straight) but a few of them (“bent leg”) are from bouts where the standing leg was bent the whole time. Most days have two bouts: 1. On the left leg until I get tired. 2. On the right leg until i get tired. I’m pretty sure there’s no effect until it becomes difficult — until the muscles are so stressed that they send out a grow signal. The whole thing is pleasant because I watch TV or a movie at the same time but, as the graph shows, it has become seriously time-consuming.