I am developing tests to measure how well my brain is working. Brief tests I can use daily. My experiences with flaxseed oil make me suspect that sometimes our brains work better and/or worse than usual for many hours or days at a time and this goes unnoticed. If these instances of better or worse function could be detected, maybe we could figure out their causes — and thereby improve how well our brains work by getting less bad stuff and more good stuff. In the case of flaxseed oil, I noticed that one morning my balance was much better than usual. I noticed this only because I was doing something unusual: putting on my shoes standing on one foot. I verified that observation with a better test of balance and later found that flaxseed oil improved my performance on several mental tests, such as speeded arithmetic.

One test I am using is a typing test: On each trial I type a random sequence of six letters four times. For example, if the sequence is “rksocn” I would type rksocnrksocnrksocnrksocn”. At the moment the measure of performance is how fast I type the 24-letter sequence. Each session consists of ten trials.

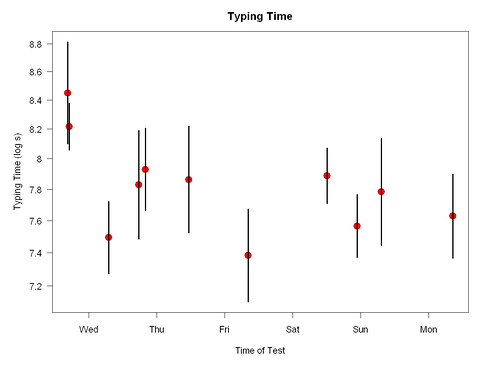

Here are the results so far:

Each point is a mean over the ten trials; the error bars show standard errors. I was glad to see there was little sign of learning after the first few sessions. Having to correct for learning would make comparison of different days more difficult.

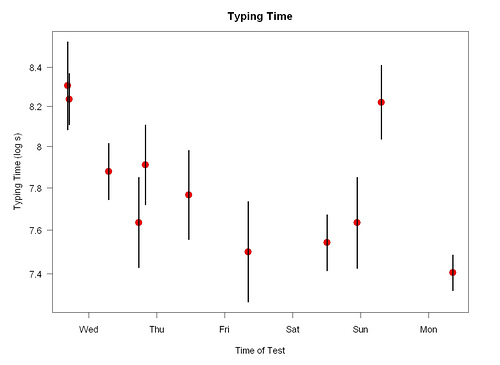

Because I am collecting a lot of data, I could look at these data more carefully. It took me a little while to do an analysis where I corrected for the difficulty of each string: Some will be easier to type than others. My first attempt at correction involved adding a factor for each letter: does the string contain an “a” (factor 1)? Does the string contain a “b” (factor 2)? And so on. This correction made a big difference: The residual mean square was almost cut in half (= sensitivity was doubled). After correcting for this, I got new estimates and standard errors for each test session:

Uh-oh! The new analysis revealed there had been something unusual about the second-to-last test session — my typing had been distinctly slower than usual. Something I ate? Unfortunately, by the time I did this analysis I could no longer remember what might have been different.

Other news on the difficulties of self experimentation: https://xkcd.com/523/

Sounds like a fairly complicated measure with the corrections involved. I have heard of a guy doing simple arithmetic selected at random to test his cognitive abilities. I just think it’s so hard to measure because (1) you will get better at anything you keep doing even if it is typing random letters, and (2) trying to make tests unique inevitably means some tests will be more difficult than others.

I don’t know of any solution to this problem; it seems that until we can all have our own personal brain imaging equipment we will simply have to accept imperfect measures.

Ben, thanks for the link. I hope to use it in my talks.

Justin, my other test is a simple arithmetic test. Corrections make a big difference there, too. As for brain imaging, you might want to see my recent post on voodoo correlations.

I do sudoku puzzles with a special rule to make them harder, and I do three in one sitting to correct for any given puzzle being too hard or easy.

(Actually, the special rule that I use is two rules: I do all the 1s first, then all the 2s, and so on. Within I number, I progress from left to right, going down the page. So first, I fill in any blank 1 in the upper-left square. Then I fill in any blank 1 in the upper-center square. Third, I fill in any blank 1 in the upper right square, and so on, until the ones are complete. The I do all the 2s. And so on.)

Using a given publisher, and staying within a given difficulty rank (I only do “hard” ones), a ‘set’ of three is a good self-test for how sharp my mind is.

I suspect that some outside experiment would verify this.

After a period of (what I will call) “burn in”, of probably the first few hundred puzzles I ever did, I have stopped learning anything. I am not improving as time goes by.

So now, on a good day, I can sit down and do three puzzles (subject to my handicapping rule, above) in 20 minutes or so. If there is something wrong with my mind (distracted, anxious, hungover, tired, etc.), I will make mistakes or take forever, or sometimes be unable to complete one.

Sometimes I’ll be stumped by a puzzle, but also know that I’m tired, or “off”–and I’ll look at the same puzzle a different day and find it easy.