Recently I listened to Robert Spector discuss his book The Mom & Pop Store: How the Unsung Heros of the American Economy are Surviving and Thriving. He had a personal connection to the subject: His father was a butcher. “As I watched him trim the meat . . . ” he said at one point. I thought: Oh-oh. To “trim” meat is to cut fat off of it.

Last spring, I bought $80 of organic grass-raised pork from a farmer near Berkeley. My order included a variety of cuts. I cooked the ones I was familiar with, leaving one I’d never seen before: pork belly. Pork belly is used to make bacon. I’ve never seen it for sale in America. Ugh, I thought. Fat. It’s 80-90% fat. I too trim the fat off meat. It sat in my freezer for a long time. Finally I decided I shouldn’t waste it. I cut it into chunks which I put in miso soup and had for lunch.

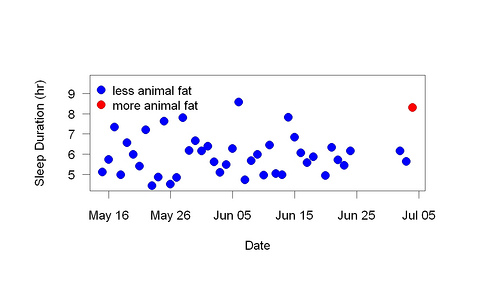

That night I slept much longer than usual (8.3 hr) and woke up feeling unusually well-rested. Here is a graph that shows my sleep duration for that night and several preceding nights:

Sleeping 8.3 hours was less common than this graph may suggest. I’d moved back to Berkeley in January and from then until the miso soup had measured how long I slept on 130 nights. I’d slept more than 8.3 hours on 2 of them (2%). Even rarer was how energetic I felt the day after the miso soup. I couldn’t quantify it, but it was very rare — once in 10 years?

Was it a coincidence — that on the very day I ate far more animal fat than usual I also slept much longer than usual and had much more energy than usual the next day? Or was it cause and effect? Here’s why the second explanation — which implies that for best health I need much more animal fat than I usually get — is plausible:

1. As Spector said, butchers cut the fat off meat. The odds that our Stone-Age ancestors, living when food was sometimes scarce, did the same thing: Zero. Perhaps our meat is unnaturally low in fat. If for a long time in our evolutionary past we ate a lot of animal fat it makes sense that our bodies would be shaped to work best with that much fat.

2. Many video games, which boys enjoy, resemble hunting. I think this reflects an evolutionary past in which men hunted. If so, for a long time humans ate meat. That they ate a lot of meat is suggested by the fact that when big game went extinct (probably due to hunting) human health got worse.

3. American culture demonizes animal fat. The conclusion that animal fat is bad rests on epidemiology. Once something becomes heavily recommended or discouraged, a big problem for epidemiologists arises: the people who follow the advice are likely to be different (e.g., more disciplined, better off) than those that don’t (the healthy-user bias). As I blogged yesterday, an example is vaccine effectiveness: Those who get vaccinated are different than those who don’t.

4. Fat tastes good. Which implies we need it. We like whipped cream, butter on toast, milk in tea, and so on. Butter vastly improves toast even with my nose clipped. Long ago, when this fat-pleasure connection evolved, dietary fat was mostly animal fat and fish oil.

All this makes it plausible that animal fat is good for us. That’s not surprising. Based on Weston Price’s observations plus these four arguments, I already believed this. Many people believe this. The interesting idea suggested by my data is the possibility of measuring its benefits quickly, by measuring brain function. My experience suggested that animal fat improves brain function quickly. Brain function is easier to measure than the functioning of other parts of the body. By measuring my sleep, my energy, or something else controlled by the brain, maybe I can figure out the optimal amount of animal fat. This is what happened with omega-3. The idea that omega-3 is good wasn’t new; the novelty was the ability to measure its benefits quickly. (At first I measured my balance, later other things controlled by the brain.) With a fast measure I could determine the optimal amount. It’s likely that what’s optimal for the brain is optimal for the rest of the body, just as all the electric appliances in your house work best with the same house current. If you figure out the best current for one appliance, you are probably simultaneously optimizing all of them.