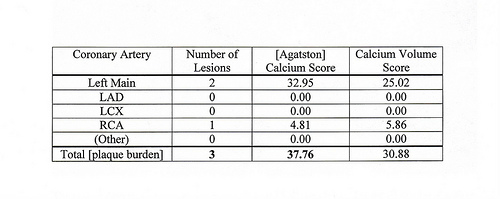

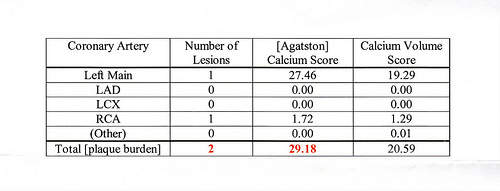

My recent heart scan results were 50% lower (= better) than predicted. Apparently I am doing something right.

You might think that my lipid values would reflect that. Not quite. They were measured twice in the last two weeks, first with a Cholestech LDX machine (instant results); second, ordinary lab tests.

Here are the scores (first test, second test). Total Cholesterol: 210, 214, which is “borderline high” (borderline bad) according to the Cholestech LDX quick reference sheet. HDL = 17, 36, which is “low” (bad). TRG = 62, 75, which is “normal”. LDL = 180, 163, which is “high” (bad).

There is no hint in these numbers that I am doing the right thing! If anything, they imply the opposite, that I’m doing the wrong thing. This supports all those people, such as Uffe Ravnskov, who say the connection between cholesterol and heart disease is badly overstated.