I wondered if Patrick Vlaskovits, who runs the question-answer site PaleoHacks, could shed some light on the recent growth of interest in a Paleo approach to health. So I asked him a few questions.

SETH What have you learned from PaleoHacks about the growth of the Paleo movement during the last year?

PATRICK Well, one thing is certain … the Paleo movement IS growing. One can look at various proxies for this — Google Trends – for example – https://www.google.com/trends?q=paleo+diet — or more frequent mentions in the mainstream media. But your question is about what I have learned from PaleoHacks.com with regard to growth. PaleoHacks.com’s traffic is definitely growing and my sense is that Paleo (by that I mean eating in an evolutionarily appropriate manner) is about to cross the chasm into the mainstream.

A few interesting measures of growth vis-a-vis PaleoHacks are:

1) The increasing frequency of meta-discussions on PaleoHacks –people who have been eating Paleo for some time are now looking to the future about what it means to be “Paleo” and how long-time Paleo eaters are changing their Paleo diets. This is, IMO, is a good thing as Keynes said: ”When the facts change, I change my mind — what do you do, sir?” We are learning more about how our health changes after some time eating Paleo – and what needs to be fine-tuned when it comes to things like bacterial/gut health (probably the most important thing to worry about) and hormonal changes relative to our environment, e.g. cortisol levels increasing due to lack of sleep which can result in unwanted/unhealthy weight gain or weight loss.

2) More people are blogging about Paleo and also more people are trying to monetize Paleo and I see them on PaleoHacks. (For the record, I have no problem with anyone trying to monetize Paleo as long as they are responsible about it as I feel that anyone monetizing Paleo should also be a good steward of Paleo.)

SETH How much has PaleoHacks traffic grown over the last year?

PATRICK Short answer: A lot. Longer answer: Depends on which metric you use — but still a lot. Ranges from 6x to 8x YOY increase in visits, uniques and page-views. Currently, PaleoHacks gets +500k page-views a month. [I double-checked my internal stats with public information on Compete.com & Quantcast – and it looks like they undercount (BTW this is a well-known and hotly debated topic).]

SETH What do you think is causing such fast growth? The broad idea is really old. Even the details are old — Weston Price wrote in the 1930s, for example. The Weston Price Foundation, which was started many years ago, is growing much more slowly.

PATRICK Cutting to the chase: no idea. Some thoughts:

Paleo’s growth appears highly correlated with CrossFit — but what has caused CrossFit’s growth? Not sure. It too has been around a while.

Social media have certainly accelerated/lubricated Paleo’s growth but I don’t if social media actually *caused* Paleo’s growth. What causes memes like Paleo to spark, and then die out or go dormant and then spark again to grow into a raging wildfire? I wish I knew.

Getting a little meta and perhaps off-topic — my assumption is that is true for most “Big Ideas”. We rarely recognize or know of their true “discovery” because for-whatever-reason the implications are not fully, if at all, appreciated at the time of discovery. For example, I believe this was the case with penicillin. A French medical student discovered it 1896, Fleming re-discovered it in 1928 and then it lay around until 1939 when Florey fully appreciated it.

I certainly didn’t put two and two together when I read Why We Get Sick back in 2000-ish. I thought it a fantastic book (and still do)– but I didn’t think of applying the evolutionary lens to diet/nutrition, even though in retrospect, it seems obvious.

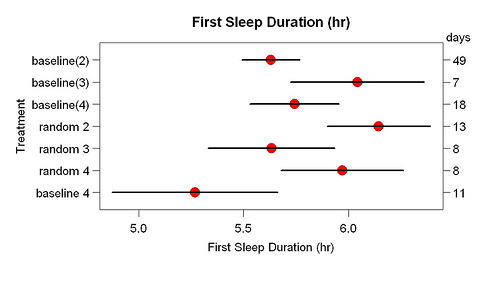

This shows means and standard errors. The number of days in each condition are on the right.

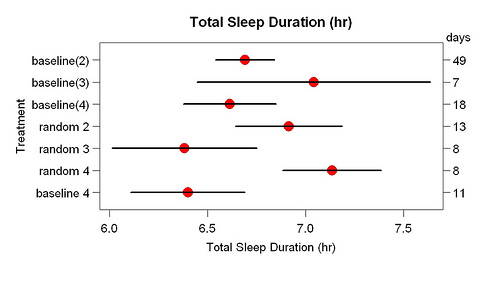

This shows means and standard errors. The number of days in each condition are on the right.