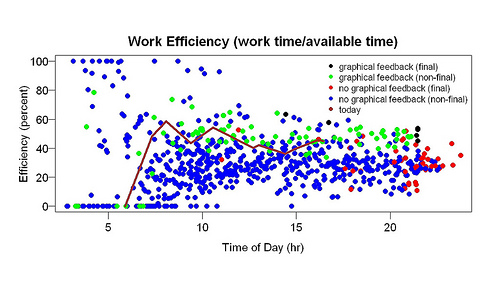

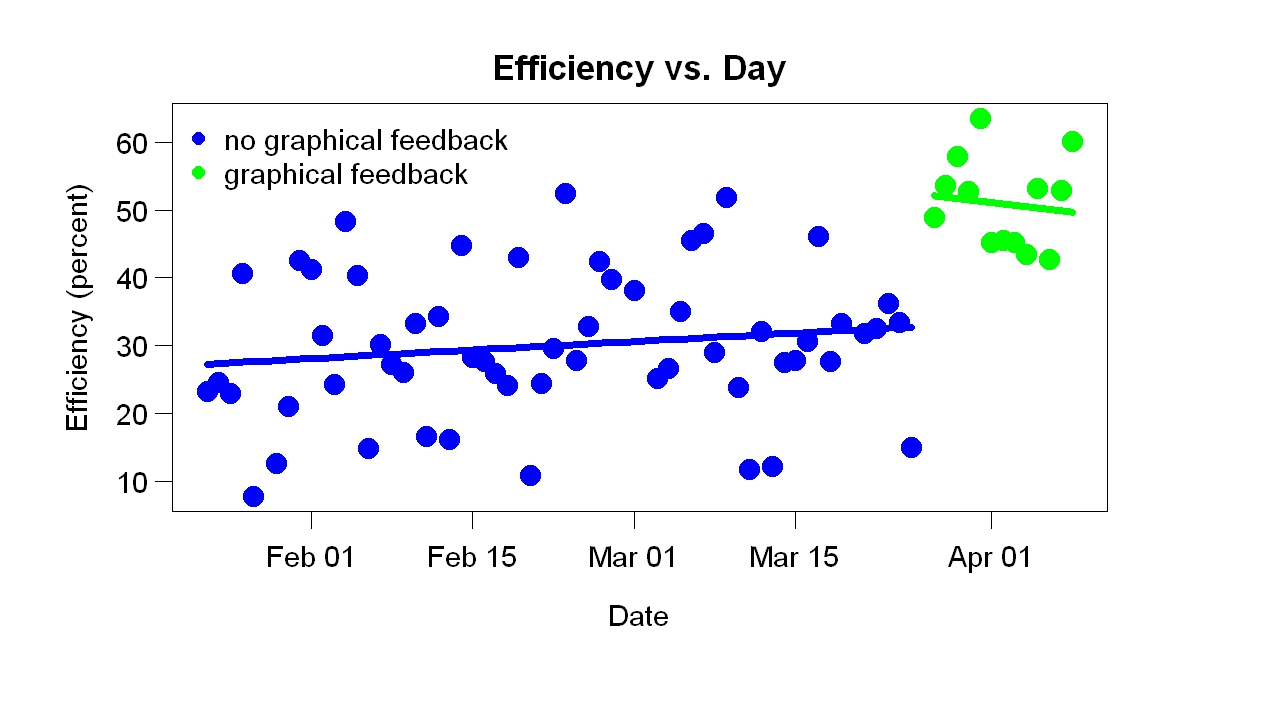

A few days ago I posted about the effect of efficiency graphs — graphs of time spent working/available time vs time of day (see below for an example). I used these graphs as feedback. They made it easy to see how my current efficiency compared to past days. As soon as I started looking at them (many times/day), my efficiency increased from about 25% to about 40%. I was surprised, you could even say shocked. Sure, I wanted to be more efficient but I had collected the data to test a quite different idea. In this post I will speculate about why the efficiency graphs helped.

Commenting on my post, a reader named Wayne suggested they helped for two reasons:

1. Motivation: You basically turned it into a contest with yourself by phrasing it as “today compared to previous days”. . .

2. Concreteness. . . . You were originally working with data in abstraction: what does “good” or “better” really mean, in realistic terms? . . . [Now] you can focus on the much more concrete: “am I doing better than in the past?”

This is a good guess. Before the graphical feedback, I had gotten plenty of non-graphical feedback: (a) how many minutes worked so far that day and (b) how many minutes during the current bout of work. Naturally I compared these numbers to previous days — certain total minutes per day and certain bout lengths were good, others were bad (e.g., working only 20 minutes before taking a break was bad, working 50 minutes before a break was good) — but I barely corrected for time of day. I vaguely knew that a certain amount by noon was good, for example. In other words, I did compare present to past, but vaguely.

Why were the efficiency graphs better than the text feedback? In addition to Wayne’s suggestions, I can think of other possible reasons:

1. Small improvements rewarded. When I was working, the line went up. Seeing this I thought good! — that is, I was rewarded. A good thing about this scheme is that it rewarded small improvements. A reward system that dispenses plenty of rewards (at the right times) will work better than a system that dispenses few of them.

2. Realistic goals. The goal — doing better than in the past — wasn’t hard to reach because the feedback was based on the whole previous distribution. I felt good if I was doing better than the median and even better the further from the median I was. This is more realistic than, say, dispensing reward only if I do better than ever before.

3. Pretty. The graphs are more attractive than a line of print (“40 minutes worked so far, 120 minutes so far today”) so I looked at them more often. Any feedback mechanism will work better if you pay more attention to it.

4. Loss aversion. Looking at the graphs caused a low-level pressure to work when I wasn’t working because I imagined the line going down. With previous feedback, loss was less obvious. With the previous feedback, if I didn’t work, minutes worked just didn’t increase; it did not go down.

5. Gentle pressure. When I didn’t work, my efficiency score went down slowly because it was based on the whole previous day, not just the last 10 minutes. This made the whole thing more sustainable.

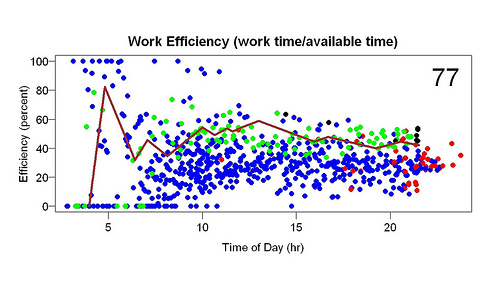

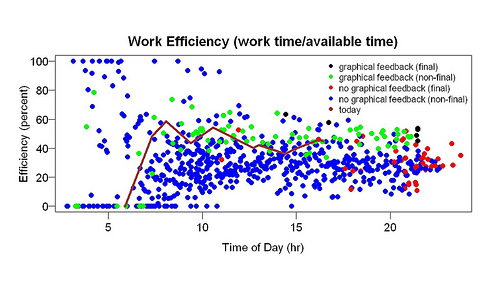

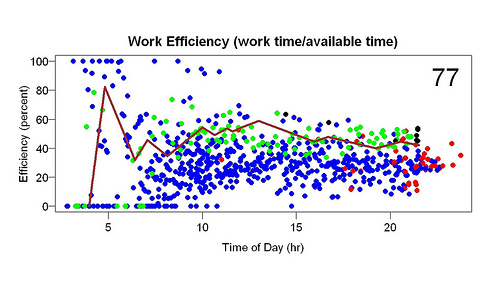

In hope of rewarding even smaller improvements, I added a number to the graph: the percentile of the current efficiency score to efficiency scores near the same time of day. Here is an example.

Each point is the start or end of a bout of work. Blue points = before graphical feedback, green points afterwards. The red and black points are the final points of the days. The brown line is the current day.

The large 77 in the upper right corner means 77th percentile, which means that the current efficiency score (shown by the end of the brown line) is in the 77th percentile compared to efficiencies measured within an hour of the same time of day. Let’s say the time was 9 pm. Then this percentile was computed using all scores (all the dots) between 8 and 10 pm. 77th percentile means that about 23% of the surrounding scores were higher, 77% lower.

The reason for this change is to make the feedback even more graded and realistic — even more sensitive to small improvements that are possible to make. My theory of human evolution says that art and decoration evolved because tools did a poor job of rewarding improvement. Until you could make the most primitive example of a tool, there was no reward for increased knowledge. The reward-vs.-knowledge function was close to a step function. Desire for art and decoration provided a more gradual reward-vs.-knowledge function. (I just finished a new write-up of that theory, which I will post soon.) . That’s what I am trying to do here.