My explanation of the Ten Commandments is that someone at the top (Moses) was trying to convince people at the bottom to join him. People at the bottom were being preyed upon. “Thou shalt not steal” meant, to Moses’s audience, “no one will steal from you — or at least we, your leaders, will discourage it.” At the very beginning of the Code of Hammarabi, another ancient set of rules, it says one purpose of the rules is “so that the strong will not harm the weak”.

I keep seeing this pattern — people at or near the top of the hierarchy making common cause with people on the bottom against people in the middle. I was reminded of it by this story:

One anecdote described a Hu Yaobang [top Chinese leader] visit that Mr. Wen arranged with Guizhou Province villagers — secretly, he wrote, because Hu Yaobang did not trust local leaders to let them speak freely.

In the 1960s, the U.S. civil rights movement gained considerable force and accomplishment when the very top of the government (first, President Kennedy and Attorney General Robert Kennedy, later President Johnson) weighed in on the side of the protesters (bottom) against the various state governments (middle).

The practical value of this alignment of forces is illustrated by How to Walk to School, a book about school reform (which I reviewed here). Two mothers of young children, Jacqueline Edelberg and another woman, wanted to improve their neighborhood schools before it was too late for their own children to benefit. On the face of it, this was impossible. But they found common cause with the principal of a local school (Susan Kurland). It goes unmentioned in the book but my impression, reading between the lines, is that the main thing that happened is that the worst teachers were shamed into leaving, above all by parents sitting in their classrooms. The principal alone could do nothing about terrible teachers; the parents alone could do nothing; together they did a lot. I spoke to Edelberg about this and she agreed with me.

I point out this pattern because it works. Judaism (Moses) still exists; people still read the Old Testament. Even more powerfully, all governments have lists of laws (Hammurabi). Jacqueline Edelberg’s neighborhood school is much better. The next big revolution in human affairs, I believe, will be health care. The current system, in which people pay vast amounts for drugs that barely work, have awful side effects, and leave intact the root cause (e.g., too little dietary omega-3), will be replaced by a much better system. The much better system will be some version of paleo. As Woody Allen predicted, people will come to believe that butter is health food.

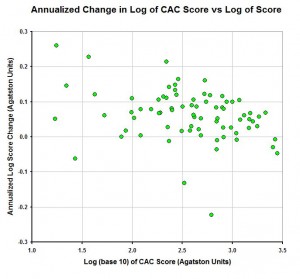

How will it happen? I suspect this pattern will be the driving force. People at the top and people at the bottom will put pressure on people in the middle. Self-experimentation, self-quantification, and personal science (which overlap greatly) are tools of people at the bottom. They cost nothing, they are available to all. When you track (quantify and record) your health problem, and show your doctor, via numbers and graphs, that the drug he prescribed didn’t work, that puts pressure on him. When you bring your doctor numbers and graphs that show a paleo solution did work, that puts even more pressure on him. The point, if it isn’t obvious, is that numbers and graphs, based on carefully collected day-after-day data, amplify what one person can do. Not just what they can learn, not just how healthy they can be, but how much they can influence others. And this amplification of influence, which I never discuss, may ultimately be the most important.