In nature animals must choose a healthy diet based on what tastes good. This doesn’t work for modern humans — lots of people eat poor diets — but why it fails is a mystery. There are many possible reasons. Are the wrong (“unnatural”) foods available (e.g., too much sugar, too little omega-3, not enough fermented food)? Is something besides food causing trouble (e.g., too little exercise, too little attention to food)? Are bad cultural beliefs too powerful (e.g., “low-fat”, desire for thinness)? Is advertising too powerful? Is convenience too powerful? Lab animals are intermediate between animals in nature and modern humans. They are not affected by cultural beliefs, advertising, and convenience (the foods they are offered are equally convenient). Their choice of food may be better than ours.

In nature animals must choose a healthy diet based on what tastes good. This doesn’t work for modern humans — lots of people eat poor diets — but why it fails is a mystery. There are many possible reasons. Are the wrong (“unnatural”) foods available (e.g., too much sugar, too little omega-3, not enough fermented food)? Is something besides food causing trouble (e.g., too little exercise, too little attention to food)? Are bad cultural beliefs too powerful (e.g., “low-fat”, desire for thinness)? Is advertising too powerful? Is convenience too powerful? Lab animals are intermediate between animals in nature and modern humans. They are not affected by cultural beliefs, advertising, and convenience (the foods they are offered are equally convenient). Their choice of food may be better than ours.

Nutrition researchers understand the value of studying what lab animals choose to eat. In 1915, the first research paper about “dietary self-selection” was published, followed by hundreds more. The general finding is that in laboratory or research settings, animals choose a relatively healthy diet. There are two variations:

[1.] Cafeteria experiments with chemically defined [= synthesized] diets showed that some of these animals, when offered the separate, purified nutrient components of their usual diet, eat the nutrients in a balance that more or less resynthesizes the original diet and that is often superior to it. [2.] Other animals eat two or more natural foods in proportions that yield a more favorable balance of nutrients than will any one of these foods alone.

Both findings imply that housing an animal in a lab does not destroy the mechanism that tells it what to eat.

Which is why I was fascinated to recently learn what Mr. T (pictured above), the pet rat of Alexandra Harney, the author of The China Price, and her husband, liked to eat. It wasn’t obvious. “We tried so many foods with him and always thought it made a powerful statement that even a wild rat turned his nose up at potato chips,” says Alexandra. “He hated most processed food. He also hated carrots, though.” Here are his top three foods:

- pate

- salmon sashimi

- scrambled eggs

Pate = protein, animal fat, complex flavors (which in nature would have been supplied by microbe-rich, i.e., fermented, food). Salmon sashimi = protein, omega=3. Scrambled eggs = ??

He liked beer in moderation, but not yogurt. “Owners of domestic rats say they love yogurt,” says Alexandra, “but Mr T only liked it briefly and then hated it, even lunging to bite a friend who brought him some. [Curious.] He loved cheese, stored bread for future consumption (but almost never ate it). Loved pesto sauce and coconut.” Note the absence of fruits and vegetables. Alexandra and her husband have no nutritional theories that I am aware of. They did not shape this list to make some point.

For me the message is: Why scrambled eggs? I too like eggs and eat them regularly and cannot explain why.

More Alex Tabarrok’s Thanksgiving post shows the connection between libertarian ideas (economies work better when more choice is allowed) and dietary self-selection.

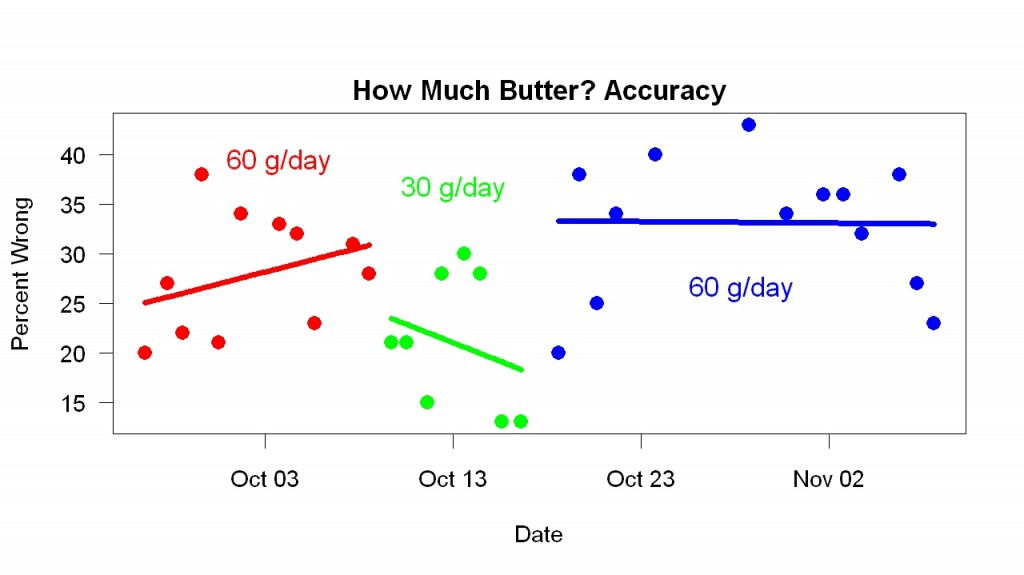

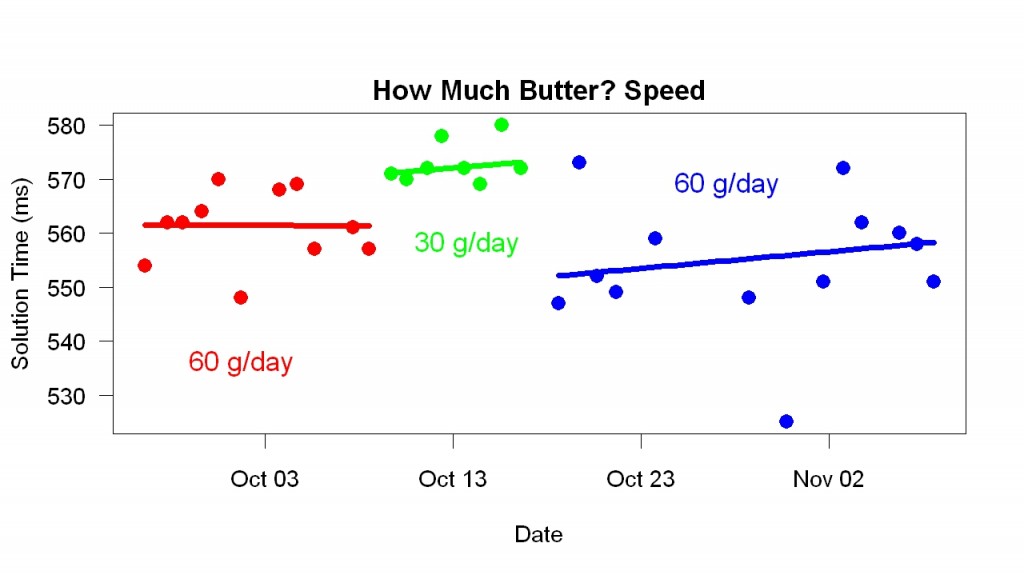

The graph shows that when I switched to 30 g/day, I became slower. When I resumed 60 g/day, I became faster. Comparing the 30 g/day results with the combination of earlier and later 60 g/day results, t = 6, p = 0.000001.

The graph shows that when I switched to 30 g/day, I became slower. When I resumed 60 g/day, I became faster. Comparing the 30 g/day results with the combination of earlier and later 60 g/day results, t = 6, p = 0.000001.