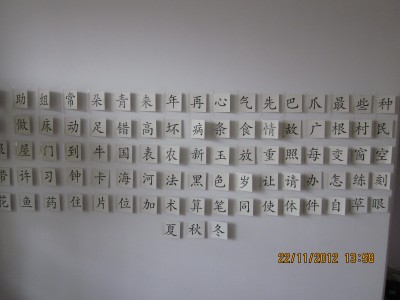

Two years ago I taped a bunch of Chinese flash cards (Chinese character on one side, English meaning on the other) to my living room wall (shown above). I’ll study them in off moments, I thought. I didn’t. It was embarrassing when guests pointed to a card and said, “What’s that?” But not embarrassing enough.

A few weeks ago, I can’t remember why, I decided to test myself: how many do I know? About 20%. I’ll try to learn more, I thought. I was astonished how fast I learned the rest. It took little time and almost no effort. I didn’t need “study sessions”. I glanced at the array now and then, looked for cards I didn’t know yet, and flipped them to find out the answer. After a few days I knew all of them.

I had been using conventional methods (flash cards studied in ordinary ways, Anki, Skritter) and an unconventional method (treadmill study) to learn this material for years. In spite of spending more than a hundred hours on each method, I had never gotten very far. I might get to 500 characters and backslide due to lack of study. Treadmill walking while studying made studying much more pleasant, but I found I would still prefer to watch TV rather than study Chinese. Maybe part of the problem was too many days skipped. After you skip four days, for example, you have a discouragingly large number of cards to review. Plainly these methods work for others. They didn’t work for me.

After my success with the two-year-old cards, I put up another array (8 x 13). I already knew about 40% of them. I learned the rest in a day or so. Then I put up a 10 x 12 array. I tested myself on them one morning. I knew 30 of them. I studied them during the day for maybe 30 minutes in little pieces throughout the day. The next morning I tested myself again (about 12 hours from the last time I had studied them). Now I knew 105 — I had learned 75 in one day, almost effortlessly. That day I studied for a few minutes. The next morning I tested myself again. Now I knew all but one of them.

I did not notice any facilitation of learning when I studied flash cards while walking around. In that case, unlike this one, (a) they were in roughly the same position relative to my body and (b) had no consistent physical location. I noticed the same facilitation of learning during a Chinese lesson in a cafe. I was having trouble remembering three Chinese words (e.g., the Chinese word that means graduate). I wrote each of them on a piece of paper with the English on one side and the Chinese on the other. I put the three pieces of paper at widely-separated places on the table. I studied them briefly, a few seconds each. That was enough. Five days later I still remember them (having used them a few times since then). This happened in a place (a cafe) with which I wasn’t familiar, unlike my living room. Maybe the general principle will be it is much easier to learn an association if it is in a new place.

It’s very early in my use of this method, but I doubt it’s a fluke. It connects with several things we (= psychology professors) already know. 1. The mnemonic device called the method of loci. You put things you want to learn in different places in a well-remembered landscape (e.g. different places in a building you know well). Usually the method is used to learn lists, such as the digits of pi or the order of cards in a deck. You place different items in the list in different places in the imagined place. Then you “walk” (in your imagination) through the imagined place. The method dates back to ancient Rome. 2. The power of interference. Thousands of experiments have shown that learning X makes it harder to learn similar Y. X and Y might be two lists, for example. The greater the similarity, the bigger the effect. What you learn on Monday makes it harder to learn stuff on Tuesday (proactive interference); what you learn on Tuesday makes it harder to remember what you learned on Monday (retroactive interference). To anyone familiar with these experiments, my discovery has a simple “explanation”: spatial interference. 3. Evolutionary plausibility. The study of printed materials (e.g., books) is so recent it is hard to imagine our brain has evolved to make it easy. In contrast, thousands and millions of years ago we had to learn about things in different places. Learning about food and danger in different places was especially important. When language arrived, the necessary learning (at first, attaching names to objects) is quite similar to my learning because the named objects were in different places. The study of vitamins and to some extent my work (especially the power of morning faces) show how hard it can be to figure out what we need for our brains and bodies to work well. How non-intuitive the answers may be.

These results suggest a new mnemonic device: Stand in front of an empty wall and imagine on the wall the associations you want to learn, each association in a different place like flashcards. This is a fast way of putting each association in a different place.

Interesting!

I know what you mean about falling behind on Anki reviews. I have over 1500 cards due right now in my Intermediate Mandarin deck.

It may even be possible to use locations in a similar way within a program like Anki. I was trying to remember that the Tuberoinfundibular pathway is in the Arcuate nucleus & that the Arcuate nucleus is in the Hypothalamus. I had a couple of cards to memorize these & just kept failing over and over again. At last, I figured it out:

Step 1. Chunk Hypothalamus, Arcuate nucleus, & Tuberinfundibular pathway together into one piece: HAT. (1st letter of each name)

Step 2. Create a spatial schematic. Mine is:

Hypothalamus

Arcuate nucleus

Tuberoinfundibular pathway

(Hopefully my spaces are not parsed out! Should be on the 2nd line & on the 3rd)

For whatever reason, this makes it incredibly easy for me to remember the components & their relation to one another. I can see it in my head, whereas before I was just *describing* it in my head.

Ha… parsed out my spaces AND my description of my spaces.

It should be like this:

Hypothalamus

__Arcuate nucleus

____Tuberoinfundibular pathway

Learning kanji is tough as fluent speakers (native and otherwise) will tell you. Anyway, the problem with these approaches is a lack of context. Take the plunge and read. A lot.

Seth: One reason I am surprised how well this works is the lack of context. Thanks for the advice.

I used Anki to review Chinese characters for Japanese (about 2100 everyday-use ones), but it would’ve been much harder without using Heisig’s mnemonic system to initially “learn” them. It’s all a waste of time if you don’t actually get any practice though. Reading isn’t such a big deal, but writing requires quite a bit of effort for me. I’ve been trying to learn shorthand, which is a whole other beast, since writing them out in full looks ridiculously unnatural. Luckily, people generally type nowadays instead.

hmmmm, outside my office is a wall-sized whiteboard, as in the entire wall is a whiteboard. i wonder if it would be helpful to write on that wall but spaced far apart as a way of studying? i can put it up, then glance at it as i walk by.

Fascinating, and it makes sense.

I seem to be a bit slow today, but could you spell out exactly what the technique is? You seem to be testing yourself with flashcards, then hanging the ones you don’t know on the wall to look at occasionally. Is that right/100% of it?

Seth: That’s close. Yes, it is very simple. I just hung a deck of flashcards on the wall. I knew some of them sort of. The technique: Put the flashcards you want to learn on the wall (as in the picture). Study them. That’s all. Result: I learned them much much faster and with much less effort than I did with other ways of studying flashcards.

This effect of ‘memory loci’ really is a strong one, and ignoring it is one major flaw of book e-readers. There is a tactile and spatial component to navigating and remembering the contents of a physical book that is almost completely missing in ebook readers.

Unfortunately, the current thinking seems to be that the indicator of current position in a book is a distraction, and the trend is to hide it most of the time. I think it actually needs to be made more prominent and ever-present

Seth: Yes, that’s a good point.

So I guess where I’m confused is how this differs from what you were doing in the first paragraph. Is it that now you actually study them, whereas before they just hung there and you mostly ignored them?

Seth: That’s right. What’s new is that I put a little bit of effort into learning them.

I’ve also been studying Chinese, with varying degrees of motivation, over the past couple years. It is a constant process of relearning things I have forgotten. But after a break, I find that I usually come back strong, relearning what I had forgotten and picking new things faster than in the past. I have noticed that it gets easier and easier to learn new characters – I assumed that it was because I have become more familiar with the radicals, tones, sounds and connections between the characters. So while there may be something to the physical spacing, don’t discount the previous hundreds of hours you’ve spent “preparing” your mind to learn.

Seth: You make good points. The sudden jump in learning speed — I never came anywhere close to learning 75 characters in a day — is what impresses me.

One other thing you might try with those flash cards on your wall, which I’ve found generally helpful, is to print the characters in colors according to tone (e.g. all first tone characters are blue, etc). Seems to make remembering the tones much easier, at least for me, when I see the character in my mind I see it in color and subsconsciously that seems to make me associate it with the tone.

Anki has a Mandarin plug-in that automatically converts pinyin into color-coded text.

Sometimes the tones it selected were wrong though & I didn’t find it that helpful, but maybe I didn’t give it enough time.

One thing I used temporarily when I was struggling with tones was to visualize the characters in a location associated with the tone. The rising tone characters were in the attic, the declining tone characters in the basement, the 3rd tone characters on a teeter-totter, & the flat tone characters were images in the flat glass table in my dining room.

If I see the character for rabbit, I know it is rabbit. I might not remember what tone it is though. Then I remember, the rabbits are all running wild in the basement & I know that rabbit must be 4th tone.

This is great.

I think this is relevant to graphical user interfaces (GUI’s) in software and web design. As you experiment with different matrix sizes and so forth, you may want to have a look at Fitt’s Law, for example, and think about the matrix density as something to play with.

The classic PC/Mac desktop is basically a detailed grid of things that one might think would be hard to remember the location of. But people perform well at this, many people even prefer messy desktops since they have little trouble remembering where things are. I once had a coworker who would occasionally just cut and paste most of the shortcuts on his Desktop (including the *old* “Old Desktop” folder) into a folder called “Old Desktop”, which was then placed in a corner of the new (mostly blank) desktop. This created a series of fossilized “layers” of desktops. He was quite fast at finding even old, obscure things with this. The Windows Phone and new Microsoft Windows 8 user interface (formerly called Metro) conventions seem to rely on this sort of capability, and take it to the next level.

Similarly, if you think about the detailed sequence of relatively precise locations many people learn with muscle memory in order to quickly navigate hierarchical menus, it’s the same — people are good at mapping positioning to recall of lots of items.

What I wonder is have you tested in a way that neutralizes the positioning during recall. In other words, is your learning still great when you can’t look at the matrix during recall?

Seth: I have done a test where the recall test for two types of study — conventional, with everything in one place, and new, with different things to be learned in different places — and found a huge advantage for the new way. However, it was just one test. I will do more tests where the testing method is the same for the two types of learning.

A wonder if this relates to Night Sky constellations with their different positions and shapes – not that far removed from the Chinese characters you’re studying. Maybe this is how we evolved to read in the first place, by pointing to different constellation and naming them.

This makes perfect sense. Look up “memory cathedral” – it’s a memory technique used for centuries, where you imagine things you need to remember being in a giant building.

I listen to a lot of podcasts on my iPhone while I’m walking around, and I try to always vary my route. I find that if I ever relisten to those podcasts, I am immediately transported back to where ever I was when I first heard it.

I’ve failed to keep up my Anki studying as well. It seems to me it ought to be part of the browser and keep track of everything- emails, feeds, flashcards, etc…

As a separate program it ends up being something I remember I am supposed to be doing whenever I am doing something else; if it were integrated almost everything (including TV) could be in it. This would be especially useful for those of us trying to limit light exposure at night- maximize our use of daylight computer hours.

Seth: cool idea.

I’m having a hard time wrapping my head around this. It’s so simple, and un-intuitive. Placing knowledge and sticking it on a place.

So now we have a mandarin wall, a programming wall (with different colors), and maybe a to do list on a fridge. Maybe that’s why people put it on the fridge. It’s accessible and people frequently goes to the fridge. Now we just need more walls. LOL