- Shio koji, a fermented food I haven’t paid enough attention to

- My experience of vegetarianism by Chris Masterjohn. “[After] a couple of weeks of eating red meat, my panic attacks completely stopped.” I suspect eating butter would have had the same effect — that the problem was lack of certain fats. A 2012 study found an association between vegetarianism and anxiety disorders (such as panic attacks).

- Higher latitudes, more multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis increases by a factor of 40 from low to high latitudes.

- Richard Nikoley’s six years of self-experimentation summed up

- Dangers of statins

- new major in Fermentation Science and Technology at Colorado State University. Smart!

Month: June 2013

Sunlight and Heart Disease

Vitamin D and Cholesterol: The Importance of the Sun (2009) by David Grimes, a British doctor, contains more than a hundred graphs and tables. Most of the book is about heart disease. Grimes argues that a great deal of heart disease is due to too little Vitamin D, usually due to too little sunlight. I recently blogged about other work by Dr. Grimes — about the rise and fall of heart disease.

Part of the book is about problems with the cholesterol hypothesis (high cholesterol causes heart disease). One study found that in men aged 56-65, there was no relationship between death rate and cholesterol level over the next thirty years, during which almost all of them died (Figure 29.2). There is a positive correlation between death rate and cholesterol level for younger men (aged 31-39). The same pattern is seen with women, except that women 60 years or older show the “wrong” correlation: women in the lowest quartile of cholesterol level have by far the highest death rate (Figure 29.5). A female friend of mine in England, who is almost 60, was recently told by her doctor that her cholesterol is dangerously high.

The book was inspired by Grimes’ discovery of a correlation between latitude and heart disease: People who lived further north had more heart disease. This association is clear in the UK, for example (Figure 32.4). Controlling for latitude, he found a correlation between hours of sunshine and heart disease rate (Table 32.3): Towns with more sunshine had less heart disease. No doubt you’ve heard that dietary fat causes heart disease. In the famous Seven Countries study, there was indeed a strong correlation between percent calories from fat and heart disease death rate (Figure 30.2). You haven’t heard that in the same study there was a strong correlation between latitude and dietary fat intake (Figure 30.8): People in the north ate more fat than people in the south. The fat-heart disease correlation in that study could easily be due to a connection between latitude and heart disease. The correlation between latitude and heart disease, on the other hand, persists when diet is controlled for.

Grimes convinced me that the latitude/sunshine correlation with heart disease reflects something important. It is large, appears in many different contexts, and has resisted explanation via confounds. Maybe sunshine reduces heart disease by increasing Vitamin D, as Grimes argues, or maybe by improving sleep — the more sunshine you get, the deeper (= better) your sleep. Sleep is enormously important in fighting off infection, and a variety of data suggest that heart disease has a microbial aspect. As long-time readers of this blog know, I take Vitamin D3 at a fixed time (8 am) every morning, thereby improving my Vitamin D status and improving my sleep.

Grimes and his book illustrate my insider/outsider rule: To make progress, you need to be close enough to the subject (enough of an insider) to have a good understanding but far enough away (enough of an outsider) to be able to speak the truth. As a doctor, Grimes is close to the study of disease etiology. However, he’s a gastroenterologist, not a cardiologist or epidemiologist. This allows him to say whatever he wants about the cause of heart disease. He won’t be punished for heretical ideas.

Myopia Increases Innovation

Big public works projects inevitably cost far more than the original budget. I heard a talk about this a few years ago. The speaker gave many examples, including Boston’s Big Dig. His explanation was that these projects would not be approved if voters were told the truth. The German newspaper magazine Der Spiegel has just published an interview with several architects responsible for recent German projects with especially large discrepancies between what people were told at the beginning and the unfolding reality — Berlin’s new airport, for example. The article’s headline calls them “debacles”. One architect gives the same explanation as the speaker I heard: “The pure truth doesn’t get you far in this business. The opera house in Sydney would never have been approved if they had known how much it would cost from the start.”

I disagree. I see the same massive underestimation of time and effort in projects that I do and that my colleagues and friends do, projects we do for ourselves that require no one’s approval. I think something will take an hour. It takes five hours. Plainly the world is more complicated than our mental model of it, sure, but there is more to it than that. Someone did a survey of people in Maryland who had been in a car accident so bad they had had to go to the hospital. Within only a year, a large fraction of them (half?) had forgotten about it. When asked if within the last year they had had an accident so bad they were hospitalized, they said no. Apparently we forget difficulties, even extreme ones, really fast. If you forget difficulties, you will underestimate them.

If I had realized how difficult everything would be, I couldn’t have done any of it is one explanation, which I’ve heard attributed to Gregory Bateson. From Malcolm Gladwell’s excellent review in this week’s New Yorker of a biography of Albert Hirschman, the economist, I learned that Hirschman — had he realized that this was human nature — would have had a different evolutionary explanation: We underestimate difficulties because this way of thinking increases innovation. Debacle . . . or opportunity? Difficulty is the mother of invention.

Occupational Specialization as Far Back as the Bronze Age

Linear B is an ancient form of Greek, used around 1500 BC (the Bronze Age) in Mycenean Greece. Stuff written in Linear B gives us one of our oldest views of human life and can reveal things that other ways of looking at the past (e.g., bones, genes, tools, pottery) cannot. At the end of The Riddle of the Labyrinth (2013) by Margalit Fox, a book about how Linear B was deciphered, is a section about what the deciphered tablets turned out to say.

One thing they revealed is considerable occupational specialization. According to Fox (pp. 273-5),

Mycenaeans plied a range of trades. Many tablets reveal the names of occupations . . . metalsmiths . . . textile work . . . tanners . . . leatherworkers . . . priests and priestesses . . . soldiers, rowers, and archers . . . swordmakers and bowmakers, chariot makers and chariot-wheel repairmen . . . goldsmiths and perfumers . . . woodcutters, carpenters, shipbuilders and net makers; fire kindlers and bath attendants; heralds, hunters, herdsmen, and beekeepers. . . . bronzesmiths.

Occupational specialization is at the center of my theory of human evolution. The decipherment of Linear B showed that it has existed as far back as we can see. Today there is an enormous amount of occupational specialization, but it also flourished when accumulated knowledge was much less.

The more you see the centrality of occupational specialization to human nature, the more you will see how modern schooling malnourishes almost everyone who undergoes it — which is almost everyone. Human nature takes people at one place and time — such as Mycenaean Greece — and pushes them to become adults who do all sorts of different things (woodcutter, herald, beekeeper . . . ). It takes people who start off the same or almost the same — same place, same food, same weather, similar genes — and creates diversity among them. Modern education tries to do the opposite: Take a diverse set of students and make them the same. One example is No Child Left Behind. Another is that in almost every college class, all students are given the same material, the same assignments, and graded on the same one-dimensional scale. We don’t need everyone to be the same; in fact, we need exactly the opposite. The more diverse we are, the sooner we will find solutions to pressing problems, because they will be attacked in many different ways.

Magic Dots User Experience (Person 1)

One of my recent posts about anti-procrastination software led a reader named Joan to an earlier post about magic dots, which is a low-tech way of getting work done. Every six minutes of work, you make a dot or line in a certain pattern on a piece of paper. I got the idea from the quasi-reinforcement effect of Neuringer and Chung. Studying pigeons, they found that markers of progress act like rewards. What was amazing was that they got pigeons to work twice as hard (= peck twice as fast) without increasing their salary (= food reward). The dots mark progress.

In her comment, Joan said

This post led me to find the post about the magic dots, which for me [have been] magic. I have a fairly boring job and lots of annoying things I have to take care of for my family, so it’s hard to get going most days. Today I got going right away and stayed on task. I didn’t use a stop-watch, just wrote down the time I started, and created the boxes. I started this yesterday afternoon, so this is one and a half days.

I asked her for details. She replied:

I have an IT job where I am pretty much self-directed, but one week out of four have to be on-call for production support, which takes up most of the time that week, and I also have to assist the on-call person the other 3 weeks when it’s an application I own. Since I spend the on-call week pretty much just monitoring 3 mailboxes, it’s very hard to focus on the off weeks, and I find myself reading blogs way too much of the time. Also, some of the production support work is interesting -figuring out what happened and how to fix it, but a lot of it is routine and annoying, like some external server was down, so we have to rerun a job.

I have tried various tools to block the most addictive sites, but am not really supposed to install stuff on my work computer. The percentage thing looked interesting, but it looked like it would be minor project to implement. Then I saw the post about magic dots. I’m a “tactile” learner, which means I like to write stuff on paper, so I thought this would be easy to try and started right away. I was already trying to keep a list and give myself checkmark rewards, without much success.

So far this week has been great — I follow this very loosely. I make a list of activities to accomplish between production support calls, including stretching, etc. and anything that is not something to be done immediately. So things that might not be “work”, but that I have to get done that day during the day are on the list, and I fill in between support work with this stuff. I count time spent chatting with co-workers, calls to my mother, calls to the bank, even this email.

The first 2 days were pretty hard. I found myself scanning the list for the least annoying or tiresome tasks, but toward the end of the day I was actually pushing myself to stay and finish a couple of issues that would fit in my time remaining, and empty those in-boxes.

I’m not that focused on filling in the dots [= completing a set of 10] as the day goes on, but after every break I start a new one, and note the time I started.

I have no idea why this works, when nothing else seems to have helped.

I asked what else she had tried. She replied:

I had some success with LeechBlock, but had to remove unauthorized apps [LeechBlock is a Firefox addon] from my desktop and [had to stop] using it to stay off the really addictive sites such as ancestry.com. Work already blocks most social media sites. I tried using the IE site blocking, but having to enter a password didn’t seem to deter me.

To try to get motivated and get more done I have:

- Affirmations and resolutions. Fail.

- Tried using a “7 habits” style to do list. Fail.

- Putting little mirrors on my desk. No help.

- Improve another habit and hope for carryover. I tried food monitoring, and spent too much time researching diets. I am keeping up with exercise goals though.

- Looked for support or monitoring sites. Did not find one that seemed like a good fit. Internet addiction forums are mostly about porn or gaming addictions, not ancestry.com or paleo diet blogs.

- I followed a popular “personal productivity” blog for a while, but in the end spent too much time reading the forums. Seems like most of these gurus have always been over-achievers.

Based on statistics I have heard, I’m only a little above average in internet use at work, but some days I’m way over.

Benefits of Brown Noise

Govind M., the Stanford student who wrote me about walking while studying, has written again to say that brown noise (deeper than white noise) makes him “calm and focused”. He discovered this while trying to find something to listen to while doing schoolwork:

I tried listening to rain, and that was ok. I know some people try to find places that are really, really quiet and then work there. But that’s pretty hard to do. Plus, it seems that the more silent the place, the more distracting individual noises potentially are. So one day I tried brown noise, because it was on the same site as the rain, and I was a fan immediately. I tried white and pink but I found them less calming and a bit too static-y. I use brown noise when I really need to focus. So any “serious” reading, writing, coding, studying, etc. I don’t know if there are contexts in which brown noise doesn’t help, but it does seem a bit much for responding to emails. . . . [It] makes the outside world melt away.

It also helps him fall asleep. He uses headphones to listen to it. Unfortunately, he said, “everyone that I have told about this thinks I am crazy.”

I tried it and quickly became a fan. Brown noise is much more pleasant than white noise. I especially like the Getting Wet preset on this page, which is close to brown noise. It does help me focus. Putting on my noise-cancelling headphones and listening to this is like being instantly transported to a faraway peaceful place. A cabin in the woods. I use it when I am doing something that takes full attention. Unlike podcasts or books, it doesn’t interfere with writing. Unlike music, it never becomes boring. (The same piece of music over and over gets boring.) Why isn’t something like brown noise piped into waiting rooms, waiting areas, and elevators?

Assorted Links

- Nassim Taleb makes a good point. There is a huge difference between using what you already know (or think you know), which is engineering, and finding out more, which is science. People who know little about science confuse science and engineering, but they do blend into each other, in the sense that science is using what you already know to learn more and engineering is full of uncertainties.

- Association of vegetarian diet and death rate (new study). The vegetarian/non-vegetarian comparison interests me less than the vegetarian/pesco-vegetarian (I call them aquaratarians) comparison, which is less confounded. The pesco-vegetarians lived substantially longer than the vegetarians.

- Levitating Beijingers. What Beijing really looks like.

The Fate of the Tiananmen Students and the Story of Edward Snowden

This post by Ron Unz made me wonder: What really happened when student protesters were removed from Tiananmen Square 25 years ago? Unz pointed to a strange website with undated blog posts (mentioned earlier), which claimed that the students were not harmed, in contrast to the usual Western view that many were harmed, even killed. I didn’t take the website seriously but I had to admit my ignorance.

I asked several Chinese friends about it. One dared reply. She wrote:

My mom once told me that she was near Beijing when the event happened. She said everything is a mess, no one can go into or out from Beijing. The army is everywhere and people are all in an angry mood, no matter the a-rmy (try to pass the possible check so use -) or the citizens. She said the students are innocent, they didn’t start the whole thing. And indeed the army was hurt first. But students are young and easy to be incited. Once the army began to take serious method, they didn’t care whether you are a student or a mob or a citizen, some innocent students hurt in the turmoil and other students try to gather together to fight back. Then everything began to lose control. After this event, all the students who participate in the sit-in were sent to poor countryside far away and never get a chance to get back to big cities in their whole life. (At that time, all the students are getting job position directly from the govern-ment, they don’t have options to choose.) My mom told me some female students were sent to countryside and raped by the local people, or have to marry to the local farmers even they have high education.

All the student protesters, according to my friend’s mother, “were sent to poor countryside” for the rest of their lives. I hadn’t read this anywhere, including Wikipedia. The fate of the protesters was far worse than I had been told by Western media.

My friend’s mother could be wrong. Even eyewitnesses can be wrong. But what people actually say, the story they tell, matters infinitely more than the truth.

I am optimistic that the story of Edward Snowden will begin to change how we talk about whistleblowing. Recent stories are not encouraging. Mark Whitacre (Archer Daniels Midland) spent 8 years in prison. That he suffered from bipolar disorder might be taken to mean that only crazy people whistleblow. Jeffrey Wigand (tobacco) was played in a movie by Russell Crowe but went from a $300,000+/year job to a $30,000/year job. Bradley Manning faces a very long prison sentence. Julian Assange has been living in the Ecuadorian embassy in London for a year, afraid to leave.

Whereas Edward Snowden, whose leaked information is at least as important, has not yet suffered terrible or even humiliating consequences. Maybe he will live the rest of his life in Iceland — as a hero. He won’t just have released enormously useful information, he will have set an encouraging example. That might be his biggest effect on the world.

Assorted Links

- A curiously short article about “why fermented foods are all the rage”

- Parents help child with disabling rare disease via complete genome sequencing

- Use of vinegar to screen for cervical cancer works as well as more expensive tests

- Charlotte’s Webcam and other children’s books for the Age of NSA

- From Vanity Fair caption writer to educational reformer. “One of the few useful skills I learned as a journalist,” he says, “is not to be intimidated.”

Thanks to Navanit Arakeri and Patrick Vlaskovits.

Nick Winter and Percentile Feedback

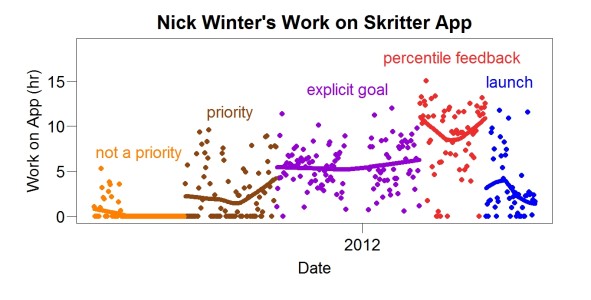

How much did percentile feedback help Nick Winter? In 2011, he wanted to finish coding a mobile app for Skritter. This graph shows his daily work on that app. Each point is a different day. The lines are loess fits.

At first, he tried to work on the app but did not make it a priority. Then he made it a priority compared to other things he did. Then he set an explicit goal (a certain number of hours of work each day) and used Beeminder to help reach that goal.

Finally he tried percentile feedback. It helped a lot. His work per day increased about 60% (to 8.6 hours/day) compared to the previous phase (5.5 hours/day). Using percentile feedback, he finished the app. During the launch, he worked on the app much less.

The data has several interesting features. One is the sudden improvement when percentile feedback started. The same thing happened to me. Another is that it helped him even though he was already making steady progress. A third is that the sudden improvement happened after he had been working on the task a long time (more than six months). Things become easier to do the more we do them but surely this change was complete by the time he started percentile feedback. Apparently it engaged a different source of motivation. Finally, he tried several things before he tried percentile feedback, implying that its value wasn’t obvious. It wasn’t obvious to me, either. I originally tried it to see what would happen. I didn’t have a strong belief it would work.

Above all, this graph shows it’s possible to learn from long-term self-measurement and what you learn may not be obvious. People who know little about research sometimes say that randomized double-blind trials are the only convincing way to learn something.