by Peter Lewis

Background

I’ve been practicing meditation on and off for years. It doesn’t interest me in a spiritual sense; I do it because I think it improves my mental function. However, what I’ve read suggests there isn’t a lot of evidence to support that. For example, John Horgan in Scientific American:

Meditation reportedly reduces stress, anxiety and depression, but it has been linked to increased negative emotions, too. Some studies indicate that meditation makes you hyper-sensitive to external stimuli; others reveal the opposite effect. Brain scans do not yield consistent results, either. For every report of heightened neural activity in the frontal cortex and decreased activity in the left parietal lobe, there exists a contrary result.

From a 2007 meta-analysis of 800+ studies:

Most clinical trials on meditation practices are generally characterized by poor methodological quality with significant threats to validity in every major quality domain assessed.

Most of this research asked questions different than mine. The studies used physical measures like blood pressure, studied complex states like depression and stress, or isolated, low-level “executive functions” like working memory. My question was simpler: Is mediation making me smarter? “Smarter” is a pretty complex thing, so I wanted to start with a broad, intuitive measure. There’s a free app called Math Workout (Android, iPhone) that I’ve been using for years. It has a feature called World Challenge that’s similar to what Seth developed to test his own brain function: it gives you fifty arithmetic problems and measures how fast you solve them. Your time is compared to all other users in the world that day. This competitive element has kept me using it regularly, even though I had no need for better math skills.

Study Design

I only had about a month, so I decided on a 24-day experiment.

Measurement. Every day for the whole experiment, I completed at least four trials with Math Workout: three successive ones in the morning, within an hour of waking up, and at least one later in the day. For each trial, I recorded my time, number of errors and the time of day. Math Workout problems range from 2+2 to squares and roots. The first ten or so are always quite easy and they get more difficult after that, but this seems to be a fixed progression, unrelated to your performance. Examples of difficult problems are 3.7 + 7.3, 93 + 18, 14 * 7, and 12² + √9. If you make a mistake, the screen flashes and you have to try again on the same problem until you get it right. As soon as you answer a problem correctly, the next one appears.

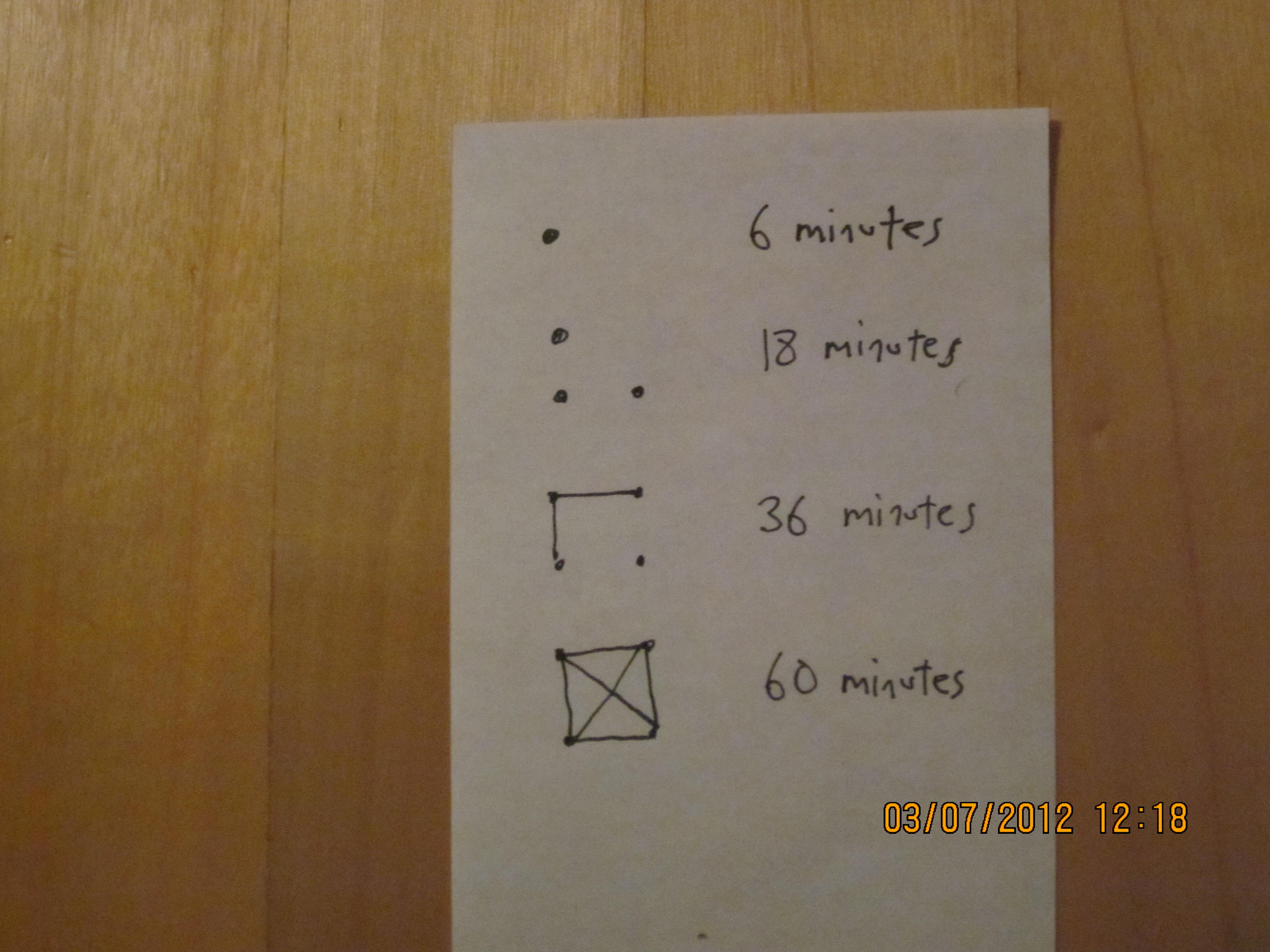

Treatment. I used an ABA design. For the first seven days, I just did the math, with no meditation. (I hadn’t been meditating at all during the 3-4 weeks before the start of the experiment.) For the next ten days, I meditated for at least ten minutes every morning within an hour of waking, and did the three successive math trials immediately afterward. I did a simple breath-counting meditation, similar to what’s described here. The recorded meditations that I gave the other participants were based on Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction program and also focused on awareness of breathing, though without the counting element. The final seven days were a second baseline period, with no meditation.

Before beginning, I posted about this experiment on Facebook, and I was pleasantly surprised to get eleven other volunteers who were willing to follow the same protocol and share their data with me. I set up online spreadsheets for each participant where they could enter their results. I also emailed them a guided ten-minute meditation in mp3 format. It was a fairly simple breathing meditation, secular and non-denominational.

Results

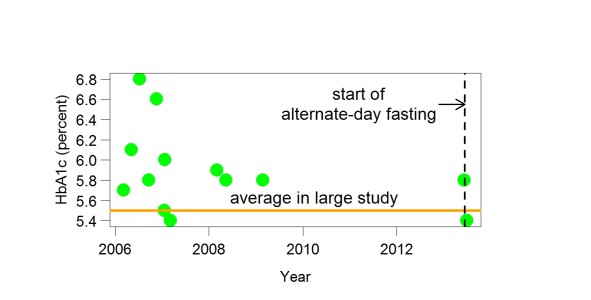

Meditation had a small positive effect. During the meditation period, my average time to correctly answer 50 problems was 75 seconds, compared to 81 during the first baseline — a drop of 7% — and the times also dropped slightly over the ten days (slope of trendline: -0.6 seconds/day). When I stopped meditating, my times trended sharply back up (slope: 1.0 seconds/day) to an average of 78 seconds during the second baseline period. These trends suggest that the effect of meditation increased with time, which is in line with what most meditaters would tell you: the longer you do it consistently, the better it works. My error rates were more flat — from 2.1 errors per 50 correct answers in the first baseline period, to 2.2 during the meditation period and 2.5 during the second baseline — and did not display the same internal trends.

(click on the graph for a larger version)

Of the other eleven subjects, six of them stuck with the experiment till the end. Their data was messier, because they were new to the app and there’s a big practice effect. Because of this, I was less focused on finding a drop from the first control period to the meditation (which you’d expect anyway from practice) and looking more for an increase in times in the second control period (which you wouldn’t expect to see unless the meditation had been helping).

Taking that into account, three of the six subjects seemed to me to display a similar positive effect to mine. Two I’d call inconclusive, and one showed a clear negative effect. (Here is the data for these other subjects.)

What I Learned

I found these results encouraging. Like Seth, I take this kind of basic math exercise to be a good proxy for general brain function. Anything that makes me better at it is likely to also improve my performance on other mental tasks. As I mentioned above, I’ve been using this particular app for years, and my times plateaued long ago, so finding a new factor that produces a noticeable difference is impressive. An obvious concern is that I was trying harder on the days that I meditated. Since it’s impossible to “blind” subjects as to whether they’ve meditated or not, I can’t think of a perfect way to correct for this. If meditation does make me faster at math, what are the mechanisms? For example, does it improve my speed at processing arithmetic problems, or my speed of recall at the ones that I knew from memory (e.g. times tables), or my decisiveness once I think I have an answer? It felt like the biggest factor was better focus. I wasn’t solving the problems faster so much as cutting down on the fractional seconds of distraction between them.

Improvements

It would have helped to have a longer first control period, as Seth and others advised me before I began. I was scheduled to present my results at this conference and at the time it was only a month away, so I decided to make the best of the time I had. Next time I’ll have a three- or four-week baseline period, especially if I’m including subjects who haven’t meditated before. The single biggest improvement would be to recruit non-meditators to follow the same protocol. Most of the other volunteers, like me, were interested because they were already positively disposed towards meditation as a daily habit. I don’t think they liked the idea of baseline periods when they couldn’t meditate, and this probably contributed to the dropout rate. (If I’d tried to put any of them in a baseline group that never meditated at all and just did math, I doubt any of that group would have finished.) It might be easier to recruit people who already use this app (or other math games) and get them to meditate than vice versa. That would also reduce the practice effect problem, and the effects of meditation might be stronger in people who are doing it for the first time. More difficult math problems might be a more sensitive measure, since I wouldn’t be answering them from memory. Nothing super-complex, just two- or three-digit numbers (253 + 178).

I’m planning to repeat this experiment myself at some point, and I’m also interested in aggregating data from others who do something similar, either in sync with me as above, or on your own timeline and protocol. I’d also appreciate suggestions for how to improve the experimental design.

Comment by Seth

The easiest way to improve this experiment would be to have longer phases. Usually you should run a phase until your measure stops changing and you have collected plenty of data during a steady state. (What “plenty of data” is depends on the strength of the treatment you are studying. Plenty of data might be 5 points or 20 points.) If it isn’t clear how long it will take to reach steady state, deciding in advance the length of a phase is not a good idea.

Another way to improve this experiment would be to do statistical tests that generate p values; this would give a better indication of the strength of the evidence. Because this experiment didn’t reach steady states, the best tests are complicated (e.g., comparison of slopes of fitted lines). With steady-state data, these tests are simple (e.g., comparison of means).

If you are sophisticated at statistics, you could look for a time-of-day effect (are tests later in the day faster?), a day-of-week effect, and so on. If these effects exist, their removal would make the experiment more sensitive. In my brain-function experiments, I use a small number of problems so that I can adjust for problem difficulty. That isn’t possible here.

These comments should not get in the way of noticing that the experiment answered the question Peter wanted to answer. I would follow up these results by studying similar treatments: listening to music for 10 minutes, sitting quietly for 10 minutes, and so on. To learn more about why meditation has an effect. The better you understand that, the better you can use it (make the effect larger, more convenient, and so on).