I haven’t seen This is Spinal Tap but I am a big fan of Harry Shearer’s Le Show, a weekly podcast. For the last few months, one segment has been about the misuse of so: People use it to start sentences that aren’t about consequences (“So we were standing there minding our own business. . . .”). I wrote Shearer to say he should change the name from Le Show to Le So. Not long after that, he ended the so segment with “here on Le So“.

Month: October 2013

Assorted Links

- Probiotics reduce frequency of colds, Cochrane review finds

- A dentist says prophylactic removal of wisdom teeth is a bad idea. “Ten million third molars (wisdom teeth) are extracted from approximately 5 million people in the United States each year at an annual cost of over $3 billion. . . . More than 11000 people suffer permanent paresthesia—numbness of the lip, tongue, and cheek—as a consequence of nerve injury during the surgery. At least two thirds of these extractions, associated costs, and injuries are unnecessary, constituting a silent epidemic of iatrogenic injury.”

- Duke University trustees defend endowment secrecy in funny ways. “David Rubenstein ’70, the Trustee chair, [says] Duke can keep a student’s grades secret — available only to a few administrators — and the principle is the same with Duke’s money.”

- Self-assembling robots

Thanks to Allan Jackson and Bob Levinson.

Omega-3 and Omega-6 in Common Foods and My Consumption

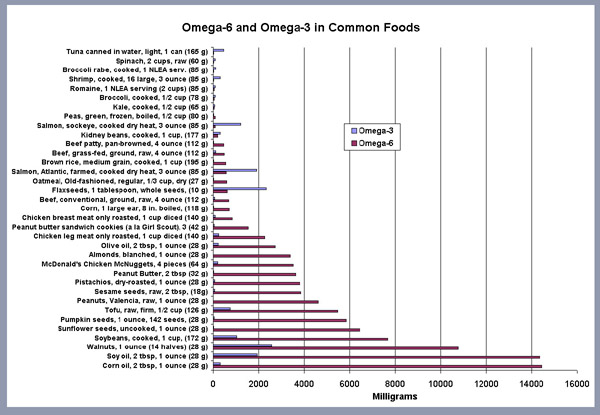

Here is a graph (source) of the omega-3 and omega-6 content of common foods. Although walnuts are relatively high in omega-3, they are much higher in omega-6. This may be why eating them reduced the performance of my lab assistants on a brain test.

When I’m in China, I eat 60 g/day of ground flaxseed. According to this graph, this provides 1.2 g/day omega-3, far more than I would get from any ordinary diet. For example, eating lots of fish would provide much less. I chose this amount based on balance and brain speed results. Flaxseed is hard to get in Beijing. Surely I am the biggest consumer in the China. I am pretty sure I am the only person ever to have optimized my intake. The best amount turned out to be surprisingly high. ”We recommend one to two tablespoons [per day],” says a website that sells flaxseed. High consumption of omega-3 should protect me against bad effects of omega-6. For example, when I eat peanuts (high in omega-6), my brain test scores don’t change.

Experts say flaxseed is a poor source of omega-3 because it provides short-chain omega-3 whereas the brain needs long-chain omega-3. My results — plenty of brain benefit from flaxseed — suggest this is wrong. The experiments that measured short-chain-to-long-chain conversion did not take account of the effect of experience on enzyme production. If you eat more of a certain food, your body will produce more of the enzymes that digest it. The subjects in the conversion experiments may have had little experience. If your long-chain omega-3 supply is limited by what enzymes can produce, you will get a steadier supply of long-chain omega-3 from enzymatic production than you will from eating the same amount all at once. For this reason dietary short-chain omega-3 could easily be a better source of long-chain omega-3 than dietary long-chain omega-3 itself.

My Theory of Human Evolution: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

From Entertainment Weekly:

EW: Are you religious?

Jodie Foster: No. I’m an atheist. But I absolutely love religions and the rituals.

Perhaps everyone enjoys rituals. (Even scientists.) It’s a curious enjoyment because rituals are arbitrary and without useful result. No other species has rituals. One sign of the pleasure we derive from rituals is obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). OCD takes many forms; one is excessive dependence on rituals, such as a need to do certain things, such as counting, tapping, or aligning, so often that it seriously interferes with being productive. The BBC program Am I Normal? did an excellent episode on OCD (no longer available). If you think of OCD (some forms) as addiction to rituals, the capacity of rituals to provide pleasure — or at least reduce anxiety — is clear.

Why do we enjoy rituals? I’ve already written about Christmas. Rituals and ceremonies, like Christmas and other gift-giving holidays, are a growth medium for fine craftsmanship. They encourage desire for fancy things – Christmas cards, special food, music, art, the special tools used in Japanese tea ceremonies. (Maybe the word fancy was invented to describe just these things, it fits so well.) They help support the highly-skilled artists and artisans who are advancing the state of their art. You can read my whole theory of human evolution here.

Assorted Links

- The science of fermented sausage and cheese

- Fermented food in Australia. “There’s a yeasty funkiness to fermented foods that I find really interesting,”

- Bad medical journalism pushes down good medical journalism. Decline of TheHeart.org. In contrast, I don’t think The New Yorker got worse after it was bought by Conde Nast.

- Whole body vibration. Clearly helps some people in chronic pain (the pain goes away). In other cases, the benefit is less clear.

Coffee Experiments: Suggestions for Improvement

Seth Brown, a “data scientist” with a Ph.D. in computational genomics, has done several experiments about the best way to make coffee. In one, he compared other people’s burr grinders to his blade grinder. There was no clear difference in taste. In another, an Aeropress apparently produced better-tasting coffee than drip extraction. He hasn’t found other factors that matter. If I drank coffee, I’d be happy to know these things.

If I were teaching how to do experiments, his work would be a good case study. I’d have my students read it and suggest improvements. The contrast between his data analysis (sophisticated) and experimental design (unsophisticated) is striking, maybe because he has no background in experimentation.

Here’s what I would have done differently:

1. Study my reactions, not the reactions of guests. He had house guests rate the coffee he made. Yet he brews coffee for himself much more often than for others — at least, he gives that impression. Since his main customer is himself, it wasn’t clear why other people’s opinions are more important than his opinion. Maybe he read somewhere that blinding is good and thought it would be easier to achieve if other people did the ratings. He could have rated coffee he made himself blinded. Put stickers on the bottom of identical cups, shuffle the cups. However, since he will usually make coffee unblinded (he will know how he made it), it isn’t clear that blinding is good.

2. No “control” experiments. In a “control” experiment, he asked guests which of two identically-made cups of coffee was better. He doesn’t say what he learned from this — apparently nothing.

3. Simultaneous presentation. He gave guests two cups of coffee made differently and asked which they preferred. Apparently he gave them one cup at a time. Simultaneous presentation, allowing them to go back and forth, would have allowed much better discrimination. Maybe the two types of grinder differed but his experiment was too noisy to detect this.

In a footnote he wrote:

Ideally, I would have liked to use better control conditions [he appears to realize that there was something wrong with his control experiment — SR], larger sample sizes, more thorough subject randomization [I have no idea what this means; his designs are within-subject. In within-subject experiments, subjects are not randomized — SR], and a more consistent testing environment.

All of these changes would have made his experiments more difficult. Maybe he has internalized the rule harder is better.

The beginning of wisdom about science is roughly the opposite: do the simplest easiest thing that will tell you something. We always know less than we think, so make as few assumptions and as little investment as possible. The easier your experiment, the less you will lose if you make a wrong assumption. The smaller your sample size, the more resources (time, money, subjects, energy) you will have left over for other experiments. Bunsen’s experiments would have been easier if he had studied himself. By studying others, he made an untested assumption that they resembled him.

I’ve done dozens of tea experiments in which I compared tea brewed two different ways. The main things I’ve learned, besides best brew times and best amounts of tea to use, are: 1. Rinse tea before brewing. It eliminates a kind of dirty taste. 2. Combine chocolate tea and black tea. The combination is better than either alone. 3. A little bit of salt helps.

Assorted Links

- blood levels of omega-3 correlated with children’s behavior. “Many, if not most UK children, probably aren’t getting enough of the long-chain Omega-3 we all need for a healthy brain, heart and immune system.”

- “Chemical brain drain”. See the comment about Dursban.

- The back pain of a friend of mine, which had lasted 20 years and was getting worse, went away when he followed this doctor‘s advice.

- Appreciation of Jane Jacobs

Thanks to Alex Chernavsky and Dave Lull.

Omega-3: More Evidence of Brain Benefit

In a study to be released Tuesday, participants with low levels of omega-3 fatty acids in their blood had slightly smaller brains and scored lower on memory and cognitive tests than people with higher blood levels of omega-3s. The changes [that is, the differences] in the brain were equivalent to about two years of normal brain aging, says the study’s lead author.

As this article recommends, I used to eat plenty of fish. But I still noticed a dramatic improvement in my balance and cognitive abilities when I started taking flaxseed oil. The best amount seemed to be 2-3 tablespoons/day. Fish wasn’t supplying close to the optimum amount of omega-3. One comment on the article was

The only proper response to this article should be, “Duh.”

I disagree. A better response is to ask How much room for improvement is there?

Why We Need Diverse Fermented Foods

I found this comment from Art Ayers deep in a discussion on his excellent blog Cooling Inflammation:

Probiotic fermenting bacteria only work in the upper part of the gut, not in the colon. The anaerobic bacteria that work in the colon must be slowly acquired by persistent eating of diverse veggies to provide diverse polysaccharides and uncooked veggies to provide the bacteria.

I agree and disagree. It’s an excellent point that the bacteria near the stomach are quite different from the bacteria deep in the colon. So you need different sources of each. I don’t know what “probiotic fermenting bacteria” are (I was under the impression that all bacteria “ferment”), but, yeah, bacteria that live on lactose (e.g., in yogurt) are going to be quite different than bacteria that live on more complex sugars that are digested more slowly than lactose and thus pass further into the intestine.

To me, this explains why I like vegetables. I have no trouble avoiding fruit, bread, rice, pasta, and so on, but I hate meals without vegetables. Why? This line of thought suggests it is because they supply complex polysaccharides needed for deep-colon health. As Ayers implies, you wouldn’t need a lot. This line of thought suggests how you or nutrition scientists can decide what fermented foods to eat (some for each part of the digestive system).

I disagree about raw vegetables. Like most people, I don’t like raw vegetables. I like the crunchiness but the taste is too weak. That most people are like me is suggested by the fact that raw vegetables are almost never eaten without dip or dressing (which add fat and flavor) or something done to make them more palatable (e.g., sugar and liquid from tomatoes). If raw vegetables were important, even necessary, for health, the fact that they are hard to eat would make no evolutionary sense.

I do like pickled/fermented vegetables of all sorts, such as kimchi and sauerkraut. I believe they are a far better source of the bacteria you need than raw vegetables (they have far more of the bacteria that grow on raw vegetables than ordinary raw vegetables).

A High School Teacher Learns About Teaching

While reading a blog post about teaching high school math, this caught my attention:

I tend to stay pretty focused on teaching; rarely do I give A Talk. Today . . . I made an exception.

[teacher] “What is it you think I want?” [student] “You want me to shut up.” . . . [teacher] “Why?” [student] “Because it’s your job!” [teacher] “Because I want everyone to pass this class.”The class’s sudden silence [made me realize] that my remark had [had] an impact. . . .

I adopt my students’ values and goals, rather than insist they adopt mine. [emphasis added. To be sure, this is an overstatement — the truth is teacher/student compromise — but you get the point.] The kids were shocked into silence [because] they realized that my most heartfelt goal was to pass everyone in the class. I learned a key lesson I still use every time I meet a new class [–] make it clear I want to help them achieve their goals, which usually involve surviving the class.

I was unclear what the “key lesson” was so — I have edited the quote to make it clearer — so I asked the teacher blogger, who replied

The key lesson is explicitly state that I adopt my students’ values and goals, rather than insist they adopt mine. My students’s awareness that I want to give them value as they define it is essential to creating the classroom environment I want.

When I began working full time as a public school teacher [after years doing test prep], I had much tougher kids [than in test prep], and my classes were not as comfortable as I was used to. It was the emptiness or worse, hostility, I got from enough of the students that bothered me. I enjoyed teaching. But I felt something missing around the edges that I’d always felt–expected–from my classrooms, and I couldn’t even really spell out what was lacking—not gone, just not universal. I didn’t know why.

So in that moment [when I told my students that my goal was to help them reach their goals] I realized that one of my greatest teaching strengths was completely under the radar [= not noticed] not only to the toughest of my public school students, but to *me*. Many of my toughest public school students, the ones that had tracking bracelets or a long history of suspensions or just three years of repeated failures—hell, not only didn’t they realize that I wanted them to achieve their academic goals, they didn’t realize they HAD academic goals, since no one had ever told them that just “passing the class” was an allowable goal. I’d never realized how essential that understanding was to the rapport and engagement I had with kids until I experienced teaching without it.

I’ve only rarely experienced that alienation or hostility since [I learned to be explicit about my priorities]. I still have to be tough and snarl and yell. But now my public school classes give me the same sense of affinity, of understanding, that my test-prep classes did.

All or almost all teachers want their kids to do well. But teachers usually define “doing well” by their own ruler, and set their goals higher than is realistic–and so are often disappointed. I think most people [including high school teachers] don’t understand the degree to which high school students feel their choices in school are completely out of their control. They can’t choose most classes, they are “helped” by giving them more of the classes they hate (double math periods for strugglers).

This supports my view that teaching is much easier when you try to help students reach their goals than when you try to get them to reach your goals. Few teachers I know have figured this out — at best, they get to different students learn differently and stop. I think it’s the beginning of wisdom about teaching. I eventually found, after years of experimentation, that (a) my students’s goals overlapped mine well enough to be acceptable to onlookers and (b) their innate desire to reach those goals was strong enough that there was no need to grade them.