Mike McInnes is a retired Scottish pharmacist and the author of The Honey Diet, published today. This book interests me because it advocates eating honey at bedtime.

Could you summarize the book?

It’s based on two ideas — that modern obesity is driven by two main factors. First, overconsumption of carbohydrates and sugars. Second, poor quality sleep. The medical profession has been saying that the cause of obesity is fat. We’ve known since the 19th century that it is carbohydrates, not fat. Poor quality sleep drives up stress hormones and appetite hormones.

In the West we have an early evening meal. We go to bed with a depleted liver. There is not enough fuel in the liver to supply the brain overnight. The way to resolve that is to forward-provision the brain, via the liver. The best food for that is honey. Honey is liver-specific. It is metabolized differently from other sugars. Honey restocks the liver prior to sleep. No other food can do this in the same way that honey can do this. Fruits are unlike honey because honey contains an army of nutrients, bioflavonoids, organic acids and others that ensure honey is not metabolized in the same way as refined sugars, which have none of these nutrients. Indeed it is fair to describe honey as the most potent anti-diabetic food known to man.

What’s the background, the history, of these ideas?

I’m a pharmacist. Sold my pharmacy. Went into sport nutrition in the late 1990s. I rapidly discovered that athletes have no concept of brain metabolism or liver store during exercise and recovery. The most critical organ of sport is the liver. I looked for a food that would provide sufficient liver supply during exercise and during recovery. When an athlete collapses, it’s not enough fuel left in the liver. Same at night, you go to sleep without sufficient fuel in the liver, after an early evening meal – and then you cannot recover physiologically – the brain is forced to activate stress and this in turn upgrades the orexigenic (appetite) hormones.

I knew from my physiological background that fructose was a key sugar to replenish the liver, fructose is liver specific – it only goes to the liver, where it is converted to glucose and stored as liver glycogen. It also brings glucose into the liver – it liberates the glucose enzyme – glucokinase and optimizes the liver (cerebral) energy reserve. Fructose is critical to replenishing the liver. At the time the usual line was the fructose goes only to muscle, and therefore had no role to play is exercise and fueling in sport.

Birmingham University did studies on fructose with success. Now every sports drink in the world contains fructose. They missed the nocturnal physiology. You have to replenish your liver before sleep. If you have a six or seven o’clock meal, you don’t have enough in the liver to see the brain through the nocturnal fast. Having discovered that honey was the key fuel to refuel the liver before sleep, I then developed the theory of replenishing the liver before sleep. Honey is the gold standard food for doing that – no other food that I know of can do this as can honey, and without digestive burden.

Have you tested other foods?

You will find thousands of studies on the Mediterranean Diet. I only know of one scientist who has written about the key question of timing. With this diet you have healthy meal that contains fruits and vegetables at 11 pm. The key principle is the timing. That would allow significant liver replenishment of the liver via the fruits and vegetables. That meant the brain had a good liver supply for sleep. The brain could activate the recovery system via the pituitary gland. That meant you were reducing the risk of all the degenerative diseases – diabetes, dementia, obesity and heart disease.

They’ve now stopped that. They now do as we do in Europe and America, they have an early evening meal. The fastest growing rate of these diseases is in the southern Mediterranean.

I just looked at the nutrient content of other foods.

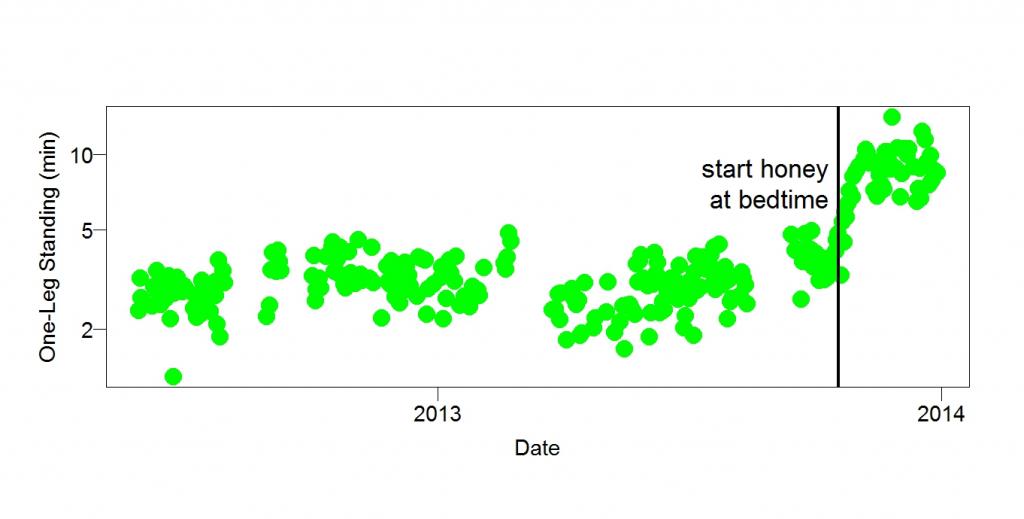

I wrote a book in 1995 based on utilizing honey at night. We got feedback from all around the world. What the effect of the honey was on nocturnal physiology. It’s not difficult to work out what’s going on, it’s quite simple. The response from readers was that honey at bedtime, in addition to better sleep, produced changes like “fitter/stronger/healthier/improved mental acuity/less nausea and morning sickness” — all of which can be attributed to reduced adrenaline/cortisol and glucagon, to nocturnal energy homeostasis, and improved anabolic profile.

For decades, people have said sleep is a low energy system. That’s wrong. Sleep is a high-energy system. Is the brain optimally fueled from the liver in advance of sleep? That’s the critical question. The brain has about 30 seconds worth of glucose. About 5 grams in the blood. The blood glucose would last 5 minutes. The only store that matters to the brain is how much reserve fuel is in the liver. Your liver has about 65-75 g of glucose in capacity. It releases 10 g every hour into the circulation – around 6-6 and a half grams to the brain. Do the math, you see the brain is in trouble at any tome is the 24 hour cycle if the liver reserve is low – especially in advance of the night fast. The brain cannot use fats for that purpose. The body cannot convert fat to glucose. Never. What it can do is during starvation it can convert fat to ketones and use the ketones for energy. But you have to be starving for that to happen. The brain must be fully provisioned prior to sleep. The gold standard food for that is honey.

What about eating a banana or apple in place of honey?

A tablespoon of honey is equivalent to a small or medium apple. However the apple doesn’t have the huge number of nutrients that affect honey’s ability to metabolize optimally in the liver and to stabilize blood glucose concentration. Honey has 200 non-nutrients that make a difference. If you took fruit at night, you would get significant liver replenishment but not as much as honey.

Of course a perfectly good case may be made for fruits and indeed vegetables before sleep since they both have an appr. 1:1 ratio of fructose to glucose, as does honey. However there are many additional nutrients in honey that improve insulin signalling, and partition and disposal of the sugars that are not in these foods – hence honey is a potent anti-diabetic food – it improves the action of two of our most widely used anti-diabetic medications – metformin and glibenclamide – I am not aware of any other sugar or sugar containing food that can do that. In the fullness of time we may find other foods/fuels that are as good as, or better than, honey, but the present knowledge is that honey is the Gold Standard. Nothing wrong with some added fiber – but not required at night, and adds digestive burden.

When is the best time to take the honey?

The honey should be taken as close to bedtime as possible.

Why that timing?

You have to do the mathematics of liver capacity and liver release. We’ve done several local studies on it. One German scientist is interested in this – Christian Benedict at Lubeck University. I wrote an earlier book on this subject that got a huge amount of responses from around the world. People saying how it transformed their sleep patterns. We found there was a significant improvement. It’s not a complicated issue.

Why call it a diet?

The only time you burn body fat exclusively is when you are sleeping. During exercise you burn both glucose and fat. You also burn muscle fat. Let’s take a 90-minute moderate intensity work out. A BBC study was done. The subject burned 19 g of fat. Overnight when the physiologist measured it he had burned 49 g of fat. What he did not understand during the exercise that although the total fat was 19 g, half of that was body fat, half was muscle fat. His attempt to explain why he burned more fat overnight was nonsense. The reason is very simple. Recovery physiology is highly expensive and exclusively ues body fat as the fuel from the circulation. If you burn 19 g during the workout then the half which is the body fat portion is 9.5 g. Now you can understand the relationship between exercise physiology and nocturnal physiology with respect to body fat used – it was 5 times as much during the night as during the workout. The key to recovery physiology is how much fuel is in liver. The study that reached that conclusion was done in 1950 and was and is ignored by the scientific establishment. It was a study on mitosis in mice. It traced the mitosis (cell division), an index to recovery. The main point was the recovery depends on the level of glycogen in the liver. This study also noted that recovery utilizes fat – again missed by the scientific establishment to this day.

Most of the stuff that I do is already there in the literature, you just need to know where to look. There’s only one scientist that I know of who has developed the same idea about sleep. Christian Benedict at Lubeck in northern Germany. The brain’s stress system is activated during the night because of the brain’s requirement for fuel. He looked at nocturnal physiology. He looked at the stress system overnight. He didn’t measure the effect of honey. It’s likely that once the book is published, there’s an important group at Lubeck called the Selfish Brain Group who are interested in the relation between cerebral energy deprivation and obesity. They are focusing on the concept that obesity is driven by chronic cerebral glucose deprivation. Basically the same as my theory. Some differences.

The foods we eat overload the circulation with energy. It means that if the glucose in that system went into the brain the brain would fry to death. The cerebral glucose pump, which is called the iPump, is suppressed. This is my theory. Consequently the glucose that you are consuming when you eat a high carb meal does not transfer into the brain. That means the brain is now deprived of energy so you are forced to go back and eat more and you repeat the cycle.

The time we burn body fat is when we are sleeping. For that to happen you have to activate the recovery system. For that to happen the brain has to have reserve fuel in the liver. If the brain does not have enough fuel in the liver it cannot activate recovery, it has to activate stress. The highest consumption of energy during the night is REM sleep and that’s when you learn. There’s another fundamental question that we need to address. The scientific and health professions will tell you if you are diabetic, you increase your risk of dementia dramatically. They’ve got that completely the wrong way around because suppressing the cerebral glucose pump is incipient dementia. It means that your brain is already deprived of energy – it’s already starving. The first thing that happens is we overload the systemic system with glucose. The second is that we overproduce insulin. Both hyperglycemia and hyperinsulin suppress the cerebellar glucose pump (iPump). That is incipient dementia. Then the excess glucose in the circulation is converted to fat via insulin. Now you’re becoming obese. Eventually your ability to keep your glucose stable by storing it as fat breaks down – you become insulin resistant – and then you become diabetic. The first system of energy impairment is in the brain. Then in the body – the sequence is first incipient dementia and chronic cerebral glucose deprivation (hunger) – then the excess circulating energy is converted to fat – then this protective mechanism breaks down – you become insulin resistant – that is diabetic.

I’m a retired pharmacist. I don’t have access to university science and study facilities. I just use the existing literature – however this is changing and a number of academics are now interested. There’s nothing that I’ve said that is not based on the literature.

If people take honey at bedtime they will lose weight?

This has been confirmed over and over again. Anecdotally, of course. Talking to athletes. Hundreds of people. After the first book, we got feedback from all around the world. Small to massive weight loss. Many people lost several stone. The new book has more science and is based on new science as well that is emerging almost daily. They’re realizing that Alzheimer’s and diabetes are basically the same disease. They still think that diabetes causes Alzheimer’s, whereas it’s the other way around. Chronic cerebellar glucose deprivation – that is incipient dementia causes obesity and diabetes. Any high energy system which is overloaded will short circuit. That’s what sugars are doing to the brain. The mechanism is very simple, sugars and insulin short-circuit the brain by suppressing the cerebral glucose pump – the iPump. If your blood sugar is too high it reduces the blood sugar/energy in the brain. That means if you have a high carb meal, less glucose enters the brain. Within 15 minutes, you’re hungry again. This is why carbohydrates make you hungry sooner. The explanation is stunningly simple.

You see people on TV who are gigantic. That’s the reason. These people are suffering from chronic cerebral hunger. The more they eat, the worse it gets.

I lost weight when I drank sugar water. Can you explain that?

I saw that. The fructose would replenish the liver. If the liver is replenished, the brain thinks that’s fine. There’s research by a guy named Maricio Russeck in Mexico. He discovered glucose receptors in the liver. He advocated the notion, which was correct, that the liver is critical in appetite control. That’s now being confirmed by recent science.

How is The Honey Diet different from the earlier book?

That book was based on restocking the liver before sleep. There’s much more science in this book. The scientific world has moved on in two ways. It’s now looking at honey in a serious way. Also, the question of low carbohydrate versus low fat diets is now becoming a major issue.

How would you sum this up?

The critical measure for the brain in all feeding and appetite regulation is based not on what’s in the blood but what’s in the liver. Russeck was spot on, 5 decades ahead of his time. These are absolutely critical questions. Let’s focus on dementia. There’s 35 million demented people in the world. That doubles every 20 years. One hundred years from now, one billion people are demented. The human brain is now shrinking, it’s not growing. That’s because one percent of those demented people is genetically driven. What is causing the other 99% of dementia, which has happened in the last 40-50 years? The answer is sugar. Refined carbohydrates. Processed foods. Honey is metabolized differently than refined sugars.

If I drink fructose and glucose in water at bedtime, it would have a different effect?

Yes, because they don’t contain the nutrients that are in honey that enable it to be metabolized differently. In America, high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) drives obesity. It overloads the liver with fructose and it’s then converted to fat.

HFCS at bedtime would have quite a different effect than honey?

Yes, for sure.