I interviewed Ms. Nussbaum, an editor at New York, about the origins of New York magazine’s Approval Matrix.

Author: Seth Roberts

Blogging: Megaphone and Microscope

If I had said to someone twenty years ago, “In twenty years there will be a way for you to say what you really think about everything related to your job, with a big audience” they would have looked at me as if I were crazy. Now, as Tyler Cowen pointed out, that’s actually the case, thanks to blogs. It’s a kind of psychological miracle. It’s due to technology, sure, but the achievement is essentially psychological.

It’s not the only psychological miracle that blogging provides. Consider this account of being in a mental hospital:

K, so since the night I got there, I would get a whiff of this nasty smell. It ‘s hard to describe, it was just nasty and I couldn’t figure out where it was coming from.

One day, I’m in my room with two roommates and I smell it.

“There it is again!” I yelled.

“It always smells like this.” The older lady said.

“OmG, you’ve been here so long, you’re used to it,” I said, repulsed. However, I still couldn’t figure out where it came from. Some times I would smell it, then go back to that same place and it would be gone. It was making me (excuse the pun) feel like I was going crazy.

After using the bathroom, I went to wash my hands. Maybe it was the soap? No.

Later, I took a shower and sniffed the shampoo that came out of the pump on the wall.

It was the friggin shampoo! No wonder I got a whiff here and a whiff there. Everyone in the building (32 people) had that crap in their hair!

Vivid, easy to read, even enjoyable to read. Now you know a little — very little, but more than zero — about what it’s like to be in such a place. I read Girl, Interrupted. Lots of movies include scenes in mental hospitals — as stylized as a Dove ad. I didn’t see Titicut Follies. Maybe Sylvia Plath wrote about it, I don’t know. It’s been nearly impossible — or actually impossible — to get an accurate idea of what it’s like to be in a mental hospital without actually visiting one. But now it is.

Anchorage = State of Being Anchored

Anchorage by Michelle Shocked is one of my favorite songs. This twenty-year-old video was put on YouTube two weeks ago. It’s as fresh and alive as the deer in my backyard.

Calorie Learning: Somewhat Better Design

I’ve done several experiments where I add a bunch of randomly-chosen spices to butter, spread the butter on saltines, eat the saltines, and then follow (or not follow) them with a piece of Wonder Bread eaten with my nose clipped shut.

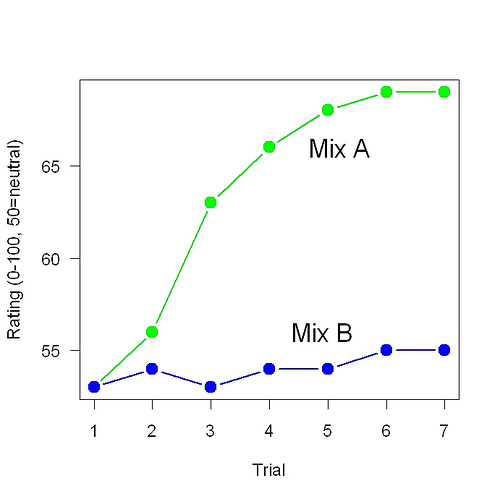

In the previous experiment in this series, I made two spice mixes, A and B. After eating saltines spread with A, I ate a piece of bread. After eating saltines spread with B, I ate nothing. I did one trial per day, going back and forth between a trial with A and a trial with B. For example, Monday (A Trial), Tuesday (B Trial), Wednesday (A Trial), etc. Here are the results:

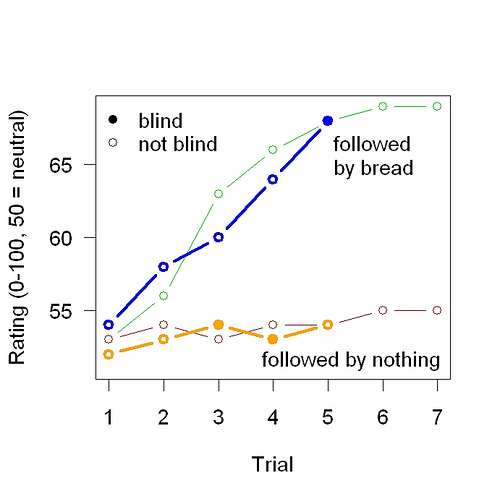

In an experiment just finished, I improved this design a bit: 1. I had trials with both A and B on the same day. (I made two new random spice mixes for this experiment.) 2. The first saltines of the day I rated “blind” — that is, without knowing what mix it was. Here are the new results superimposed on the previous results.

So far so good. The new results agree with the earlier results.

How Amazon Computes Book Ranks

Given how interested authors are in the Amazon rank of their books, it’s curious how little I can find about how those ranks are computed. Amazon won’t say. Let me try to figure it out.

Is it based on the number of copies sold in some unit of time — say, one day? Surely not. If the unit is too small, then most books will have zero copies sold. That’s too many ties. If the unit is too large — say, one week — it won’t change very quickly. That’s boring.

That leaves average time between orders — what an animal psychologist would call interorder interval (IOI). If one copy is sold at 10:00 am on Monday and the next copy is sold at 12 noon on Tuesday, the IOI is 26 hours. This is easy to track for each book and can discriminate between books that don’t sell many copies.

How many IOIs does Amazon use to compute the rank? One, five, twenty? Surely more than one. Using just one would be too noisy and would do a terrible job of discriminating best-sellers. This morning my editor asked me if Stephen Dubner’s Freakonomics blog post about SLD yesterday helped its Amazon rank. I checked: the rank was about 5600 (better than usual). This afternoon, I checked again: the rank was about 1700. I am sure there is no delayed effect of a mention on the NY Times website; Dubner’s post must have had its biggest effect on sales yesterday. So why is the rank improving today? Because Amazon uses a fixed number of IOIs (or at least a maximum number) to compute the rank and today the longer ones are still being replaced by shorter ones. In other words, the rate of sales, although lower today than yesterday, is still higher than usual.

According to this article, a book ranked about 2000 sells about 10 copies per day (on Amazon, I assume). SLD’s current rank (about 2000) reflects an average of long IOIs (before yesterday) and short ones (yesterday and today). Yesterday, therefore, it must have sold more than 10 copies — but this wasn’t enough to get rid of all the long IOIs. So the rank is based on more than 10 IOIs.

Further than that I cannot go.

Using Amazon rank to compute sales. The Bookscan/Amazon-rank correlation I show in that post indicates that a book with an Amazon rank of about 2000 sells about 40 Bookscan copies per day, which is why I assume that the 10 copies per day mentioned above refers just to Amazon sales.

The China/Tourist Interface

When I gave a draft of my Robert Gallo article to my editor at Spy, Susan Morrison, she called it “well-reported.” I hadn’t heard the term before, but I understood what it meant. (And, yes, I do remember every compliment I have ever been given.)

I thought of well-reported when I read this in The Fortune-Cookie Chronicles by Jennifer Lee:

This eighty-one-year old Chinese woman was a professional Jew.

She lives in Kaifung, China, where long ago there had been a community of Jews large enough to build a synagogue. She is one of the few Jews left; pilgrims visit her. She makes a living selling them paper cutouts that combine Jewish and Chinese themes. You could read a hundred books about China and not come across anything like this, but it reminds me of my experience. When I was in China — I taught psychology at Beijing University — some friends and I visited the Great Wall. To avoid tourists, we went to a remote and less popular section. As predicted, it was nearly deserted. But along the path to the wall, just before it got steep, sat an old man in a chair. “2 yuan” said a sign. He wanted 2 yuan (about 25 cents) to allow us to pass. We paid.

What Do Iceland and Sierra Leone Have in Common?

Something important. After reading this, my question is: What else has John Carlin written?

Self-Experimentation and the Nicotine Patch

Murray Jarvik, inventor of the nicotine patch, died recently. I learned:

When the researchers could not get approval to run experiments on any subjects, they tested their idea on themselves. “We put the tobacco on our skin and waited to see what would happen,” Jarvik recalls. “Our heart rates increased, adrenaline began pumping, all the things that happen to smokers.”

Why, I wonder, didn’t they start with self-experimentation?

Read-Off

Or should that be Write-Off? Last night I compared, as in a cook-off, the first few pages of four books I want to read. (I also want to read Cookoff by Amy Sutherland.) Here are my notes:

1. The Geography of Bliss: One Grump’s Search for the Happiest Places in the World by Eric Weiner. Slow start. Weiner goes to Rotterdam to visit happiness researcher Ruut Veerhoven. I am unamused that a Dutch waiter asks “Maybe now you would like some intercourse?”

2. Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution by Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins, L. Hunter Lovins. Disappointing, although possibly a great book. The beginning is abstract and preachy — although the central idea — we are beginning an industrial transformation that will transform our lives as much as the Industrial Revolution did — is incredibly important.

3. The Man Who Loved China: The Fantastic Story of the Eccentric Scientist who Unlocked the Mysteries of the Middle Kingdom by Simon Winchester. About Joseph Needham. Another slow start. Begins with his arrival in China. No amount of well-written detail will make someone getting off a boat or plane interesting, although I expect the rest of the book will be excellent. Here’s how the USA Today review of the book begins:

Simon Winchester’s The Man Who Loved China proves the adage that if you really want to learn a foreign language, fall in love with a native speaker.Winchester’s new non-fiction book is the tale of what happened after brilliant British scientist Joseph Needham lost his heart to Lu Gwei-djen, a 33-year-old Chinese biochemist. She had come to Cambridge University from China in 1937 to meet with Needham, 37, and his wife Dorothy, also a prominent biochemist.

Much better.

4. The Fortune Cookie Chronicles: Adventures in the World of Chinese Food by Jennifer 8. Lee. (I have no idea why Lee spells her name with a period after the 8.) This was the book I kept reading. After a poor prologue (a cluster of Powerball winners due to a fortune-cookie fortune — unsurprising), the book moves to a well-written mix of stuff I didn’t know about an interesting topic (Chinese take-out) and personal story.

Winner: The Fortune Cookie Chronicles.

Ditto Soda: Compliment or Coincidence?

Which of the following doesn’t belong?

- Fanta

- Dr. Pepper

- Coke

- Pepsi

- Skipper

- Parker

- 7Up

- Sprite

- Mountain Dew

- Mr. Pibb

- Ditto

All are names of soft drinks. Ditto is the name of a new lemon-lime drink that is the Safeway house brand. It strikes me as so different than the other names on the list that I flatter myself to think that there is some connection with my invention of the term ditto food in The Shangri-La Diet. Soft drinks are prototypical ditto foods.

A few years before Nabokov’s novel Lolita was published, a short story by Dorothy Parker titled “Lolita” appeared in The New Yorker. Nabokov had published often in The New Yorker, and he wrote an angry letter to Katherine White, the fiction editor, complaining that the manuscript of Lolita that he had shown them in confidence had somehow leaked. White wrote back that it was a coincidence.