At the upcoming QS Conference (May 28-9, San Jose), Robin Barooah and I will run a session about self-experimentation. Alexandra Carmichael asked me to write a post about how to do self-experimentation as a kind of advertisement for the session. Robin and I will be giving examples of what we have done and what we learned from them. Here’s some of what I’ve learned.

1. Easier to learn useful stuff than I expected. In contrast to the rest of life, where things turn out harder than expected, learning useful stuff by self-experimentation was always easier than I expected, in the sense that the benefit/cost ratio was unexpectedly high. I learned useful things I never expected to learn. An example is acne. When I was a grad student I had acne. My dermatologist had prescribed two drugs, tetracycline and benzoyl peroxide. I believed that the tetracycline worked and the benzoyl peroxide did not work. My results showed the opposite. It hadn’t occurred to me that I could be so wrong, nor that my dermatologist could be wrong (he believed both worked), nor that the establishment view (treat acne with tetracycline) could so easily be shown to be wrong.

2. Don’t be afraid of subjective measurements. By subjective measurements I mean non-physical measurements, such as ratings of mood or how rested I felt — what professional researchers call “self-report”. They routinely say self-report is misleading. At first, I wondered if my expectations and hopes would distort the measurements. As far as I can tell, that didn’t happen. Instead, I found such measurements helped me learn plenty of useful stuff I couldn’t have learned without it. For example, I learned how to improve my mood and how to wake up more rested.

3. Complex experimental designs were rarely worth the extra effort. Now and then I tried relatively complex experimental designs (e.g., randomization, a factorial experiment). Usually they were too hard.

4. Run conditions until you get 5-40 days of flat results (flat = what you are measuring is not going up or down). Ideal is 10-20 days. Suppose I want to compare Treatments A and B (e.g., different amounts of butter). I decide to make one measurement/day. The first step would be to do A for several days. I keep doing A until whatever I am measuring (e.g., sleep) stops steadily increasing or decreasing and then run several more days — ideally, 10-20. Then I do B for several days. I keep doing B until my measurement stops changing, then I do 10-20 more days of B. If the B measurements looked different from the A measurements, I would then return to Treatment A. It’s always a good idea to run a treatment until your central measurement stops changing, and then run it longer. How much longer? I’ve found that less than 5 days makes me nervous. Whereas running a condition for more than 40 days of flat results is a wasted opportunity to learn more by trying a different treatment.

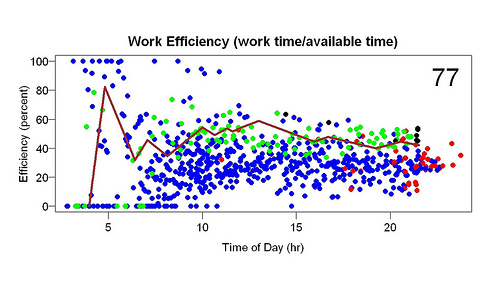

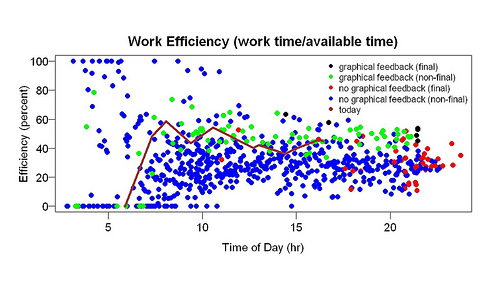

5. Data analysis is easy. The most important thing is to plot measurement versus day. It will tell you most of what you want to know. For example, most of the graphs in this paper show whatever I was measuring (sleep, weight, etc.) as a function of day.

6. When you add data, look again at all the data. Each time I collect new data, I plot all of the data, or at least a large chunk of it. This helps spot unexpected changes. For example, each time I measure my weight I look at a plot of my weight over the last year or so. Recently I found that cold showers caused me to gain weight, which I hadn’t expected. If I hadn’t looked at a year of data every time I weighed myself, it would have taken longer to notice this.

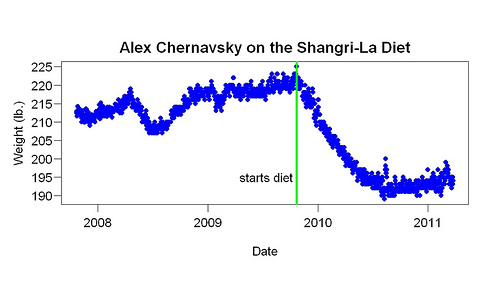

7. Don’t adjust your set. My conclusions often contradicted expert opinion. Again and again, however, other data suggested my self-experimental conclusions were correct. Acne is one example. Later research supported my conclusion that tetracycline didn’t work. Another example is breakfast. Experts say breakfast is “the most important meal of the day.” I found it caused me to wake up too early. When I stopped eating it, my sleep got better. Other data supported my conclusion. The Shangri-La Diet is a third example. According to experts, it should never work. Hundreds of stories show it works at least some of time.

The most useful lesson I learned was the most basic. You will be tempted to do something complicated. Don’t. Do the simplest easiest thing that will tell you something. The world was always more complicated than I realized. Eventually it sank in: Complicated (experiment) plus complicated (world) = confusion. Simple (experiment) plus complicated (world) = progress.