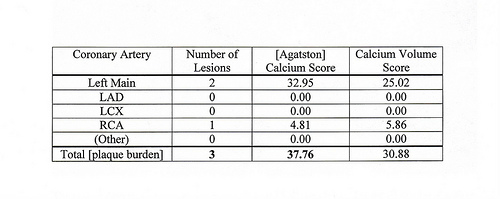

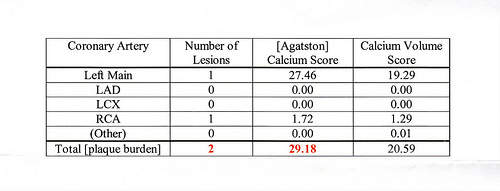

My recent heart scan score was about 50% less than you’d expect from an earlier score. Why the improvement?

During the year between the two tests, I’d made one big change: eat much more animal fat. That’s the obvious explanation. Three things support it:

1. Mozaffarian et al., as I blogged, found a similar result.

2. The animal fat (pork fat and butter) had both produced large immediate improvements when I began to eat them. The pork fat had improved my sleep; the butter, my arithmetic scores. This sort of large immediate effect we associate with the supply of a missing necessary nutrient — giving Vitamin C to someone with scurvy, for example. My brain, at least, needed much more animal fat than I’d been eating. Different parts of the body need different nutrients, sure, but they all must work well with the same set of nutrients. If Nutrient X helps one part of the body, it is more likely to help another part.

3. My initial score put me at the 50th percentile for my age. I’d had an unusual diet for a long time. I stopped eating bread, potatoes, rice, pasta, and dessert 13 years ago. I’d started consuming lots of omega-3 and fermented foods a few years earlier. It was possible that those other changes produced improvement but if so it was a strange coincidence that, as my score got better and better over the years, I happened to measure it for the first time just when it crossed the 50th percentile.

This explanation makes a prediction: If you greatly increase your animal-fat intake, your heart scan score should improve. A commenter said what he’d read on paleo-diet forums supported this prediction: “If you hang out in the paleo/low carb forums, you see this kind of thing a lot.”