From a BBC documentary called Are We Still Evolving? I learned that after the development of farming there was intense selection in Europe for “lactose tolerance” — meaning the ability to digest lactose as an adult, which requires the enzyme lactase. (The technical name is lactase persistence.) The necessary gene spread rapidly. Now most Europeans have the gene. In Ireland almost everyone has the gene. Mark Thomas, an evolutionary geneticist interviewed on the show, who does research on lactose tolerance, said this:

It’s probably the most advantageous characteristic that Europeans have evolved in the last 30,000 years.. . . The advantage that’s been measured is just incredible, absolutely incredible, how big an advantage it was for these early farmers in Europe.

“Why would drinking milk into adulthood be so strongly selected for?” asked Alice Roberts, the presenter. Thomas replied,

Milk has got lots of energy in it, it’s very nutrient dense, it’s got lots of other goodies, like various vitamins, calcium, and so on. Also, it’s a relatively clean fluid, so it’s much better than drinking stream water or river water or well water or something like that. Another advantage is if you’re growing crops you have a boom and bust in terms of the food supply.

Not a word about butterfat — “lots of energy” is true of all fats. The rapid spread, the “incredible” advantage, suggests that milk supplied something resembling a necessary nutrient. As if everyone had been suffering from scurvy and the new gene allowed them to eat citrus — something like that. Such a gene would spread rapidly.

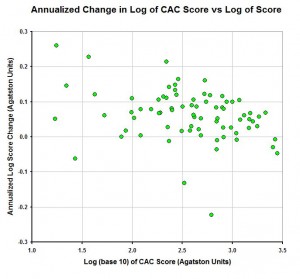

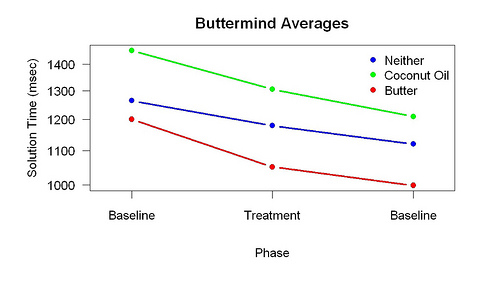

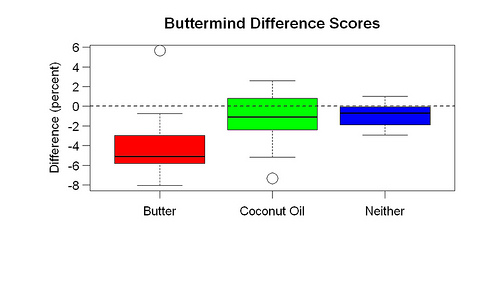

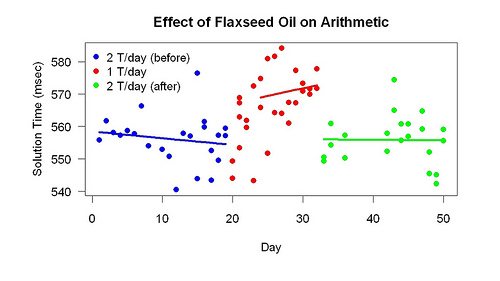

Does milk supply a necessary nutrient? My results suggest that butter — half a stick (60 g)/day — provides two clear benefits: 1. Better brain function. 2. Less risk of heart disease (probably). As far as I can tell, roughly everyone in America would get these benefits because their diets now lack enough of whatever it is. Both benefits reflect invisible problems. Like everyone else, I had no idea my brain function could be substantially improved and had no idea of my rate of progression (narrowing of arteries) toward atherosclerosis. Only because of unusual tests (the arithmetic test and a “heart scan”) did I notice sudden large improvements when I started eating lots of butter — what you’d expected from addition of a missing necessary nutrient. This explains why Thomas and almost everyone else is unaware of these benefits.

Keep in mind that before I started eating butter, I already ate a high-fat low-carbohydrate diet. Yet I wasn’t getting enough of something in butter. I already ate lots of pork fat. Perhaps the saturated fat in butter is better digested than the saturated fat in pork. Or perhaps the fat profile is better.

If lactose tolerance is so helpful, why are most Asians lactose intolerant? My work suggests two answers: 1. Yogurt. Long ago, Asians ate lots of yogurt. I know the Mongols did. There are present-day indications of this. The Chinese appreciate the value of yogurt more than Americans. Yogurt is more common in Chinese supermarkets than American ones. Yogurt makers are better and more common in China than Europe and America. Lots of Chinese make their own yogurt; as far as I can tell, home yogurt making is more popular in China than America. You can buy a cheap good yogurt maker many places in Beijing, unlike San Francisco. Yogurt provided butterfat. 2. Pork. The Chinese, of course, eat far more pork than Europeans. Unlike cows, pigs supply a cut with a large amount of fat: pork belly. I found it easy to get plenty of pork belly in China and eat it as the main course. Difficulty getting pork belly in the Bay Area is what pushed me to eat butter. This view predicts that European farmers raised more cows than pigs.

Anyway, to summarize, the great advantage conferred by lactose tolerance suggests the great value of something in milk if you eat a European-farmer-like diet. My work supports this; it suggests the crucial ingredient is butterfat. Which many Americans carefully avoid!

Note: The danger posed by the high level of AGEs (advanced glycation endproducts) in butter I don’t know about — but of course this danger has nothing to do with why lactose tolerance was so beneficial. My experience so far (the heart-scan improvement) suggests that that ordinary butter is not “artery-constricting”. Presumably AGEs are formed when milk is pasteurized so I would prefer to eat unpasteurized butter.