Yesterday I blogged about a sudden improvement in how fast I could do arithmetic. The improvement was much larger than normal variation and happened after I did four things that I rarely did. In chronological order:

1. Ate about 30 g of butter.

2. Stood on a cobblestone mat (for 5 minutes, which was all I could bear).

3. Stood during the test.

4. Walked for 10 minutes just before the test.

To find out which mattered, I did them again in the same order and at the same times of day, but with tests before and after each one. If performance suddenly improved after one of them, then I’d know.

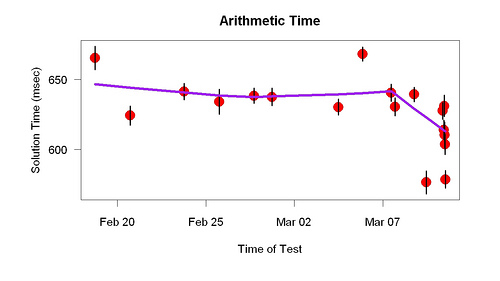

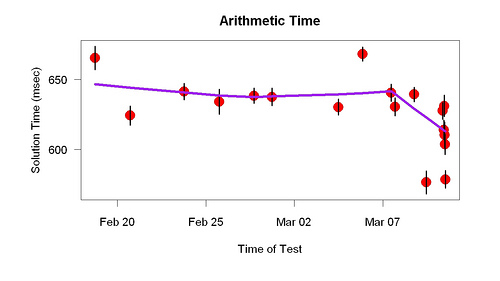

Here’s what actually happened.

The last six points are the relevant results. The first of the six points (627 msec) was before everything. The second (613 msec) was after butter but before the cobblestones. The third (630 msec) was after the cobblestones but before standing. The fourth (610 msec) and fifth (603 msec) were while standing but before walking. The final one (581 msec) was while standing after walking.

I was surprised and pleased how closely the first and last scores repeated the earlier difference. The first score was close to the previous baseline; the last score was close to the previous outlier. A big improvement seems to be under my control.

Before doing these tests, my best guess about what caused the improvement was the walking. But the scores were improving before the walking so that’s unlikely. Perhaps the walking was one of several factors that helped. The data suggest, if anything, a shocking conclusion: butter made my brain work better. An alternative, less consistent with Occam’s razor, is that butter, standing, and walking all produced smaller improvements, which together added up to the big improvement. The cobblestones produced a short-lived decrement.

That pork fat improved my sleep obviously supports the butter interpretation. I should be less surprised than anyone else, but still . . . Last week I noticed something else that supports the butter explanation. At a restaurant with a friend, the waiter brought bread and olive oil. I asked for butter. I spread all of it on a piece of bread, then asked for more butter, and spread all of that on another piece of bread. (About 30 g butter total.) It was the first time I’d eaten a large amount of butter at a meal. An hour or so later, I felt unusually good, some combination of calm and warmth. I never noticed this after eating pork fat, but butter may be to pork fat as hamburger is to steak: Easier to digest. The pork fat is within cell walls; the butter fat isn’t.