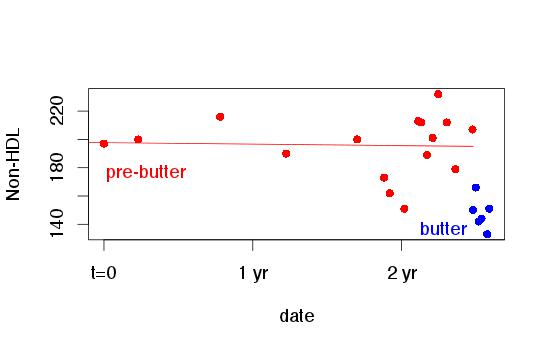

I measure my arithmetic speed (how fast I do simple arithmetic problems, such as 3+ 4) daily. I assume it reflects overall brain function. I assume something that improves brain function will make me faster at arithmetic.

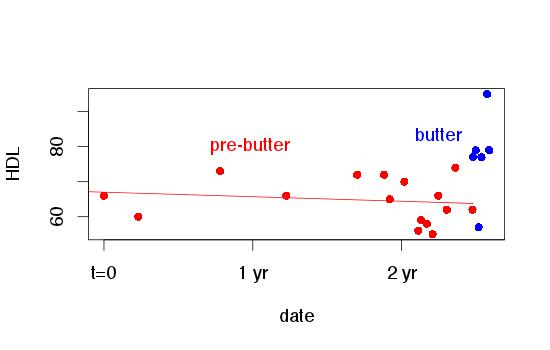

Two years ago I discovered that butter — more precisely, substitution of butter for pork fat — made me faster. This raised the question: how much is best? For a long time I ate 60 g of butter (= 4 tablespoons = half a stick) per day. Was that optimal? I couldn’t easily eat more but I could easily eat less.

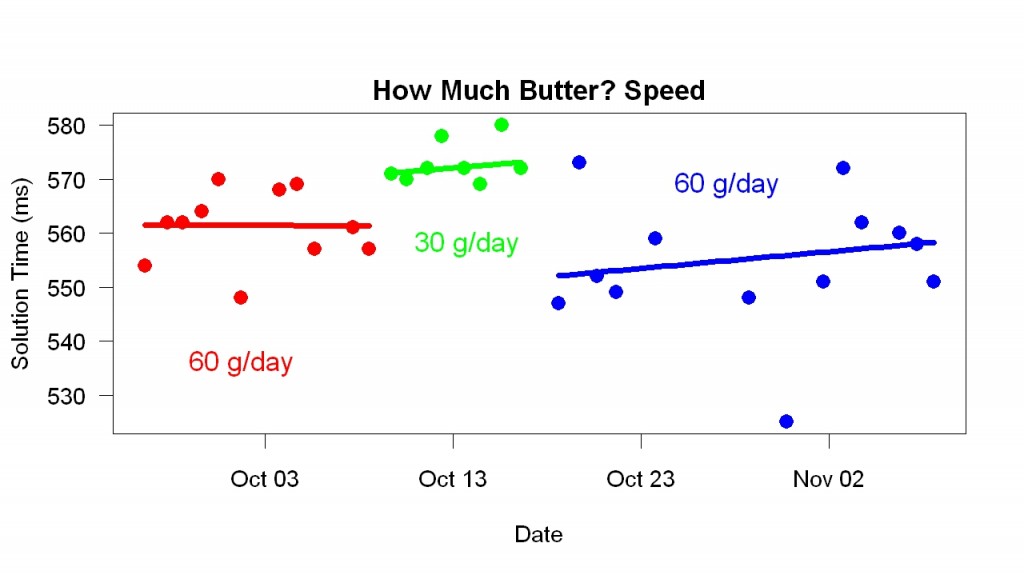

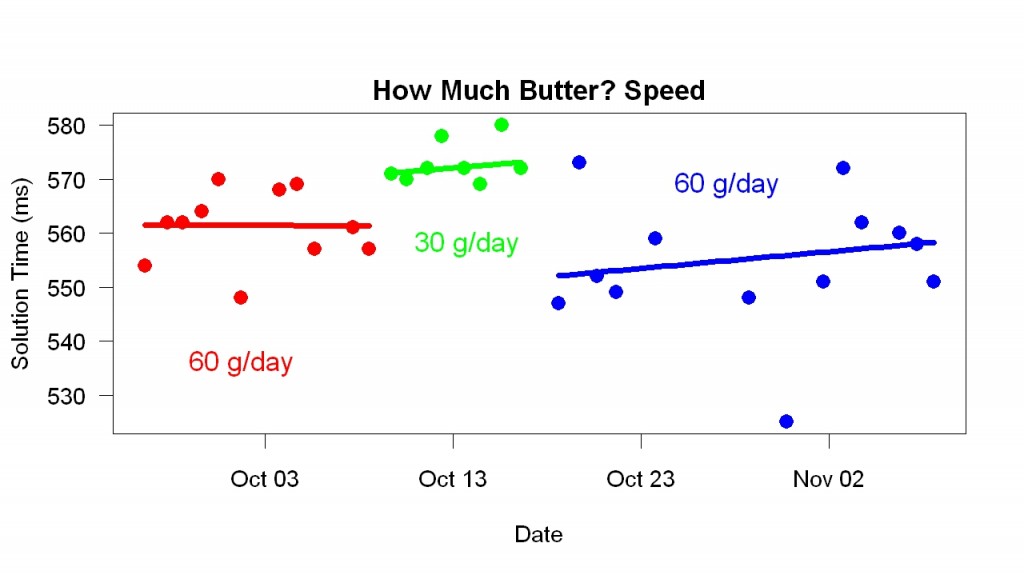

To find out, I did an experiment. At first I continued my usual intake (60 g /day). Then I ate 30 g/day for several days. Finally I returned to 60 g/day. Here are the main results:

The graph shows that when I switched to 30 g/day, I became slower. When I resumed 60 g/day, I became faster. Comparing the 30 g/day results with the combination of earlier and later 60 g/day results, t = 6, p = 0.000001.

The graph shows that when I switched to 30 g/day, I became slower. When I resumed 60 g/day, I became faster. Comparing the 30 g/day results with the combination of earlier and later 60 g/day results, t = 6, p = 0.000001.

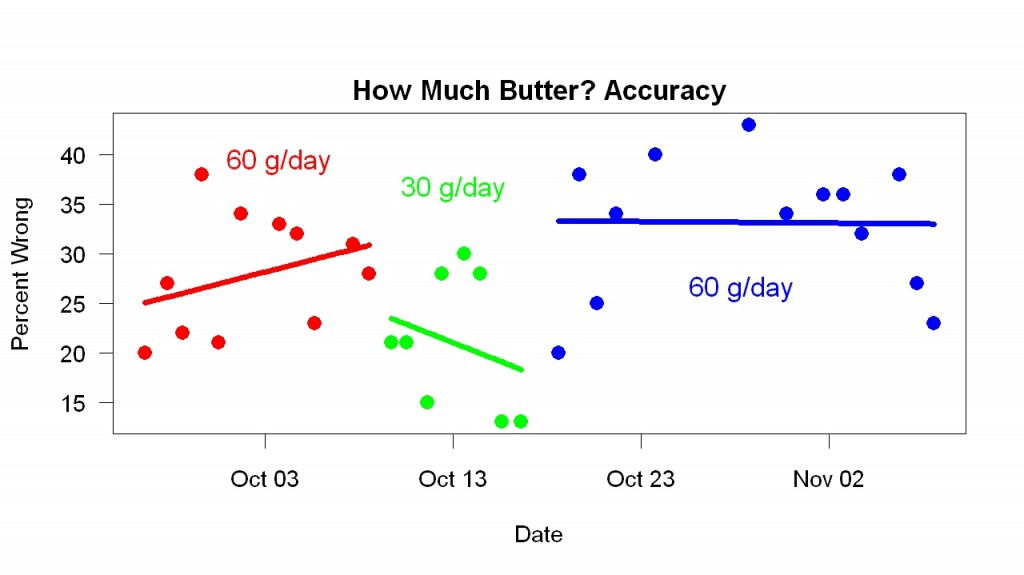

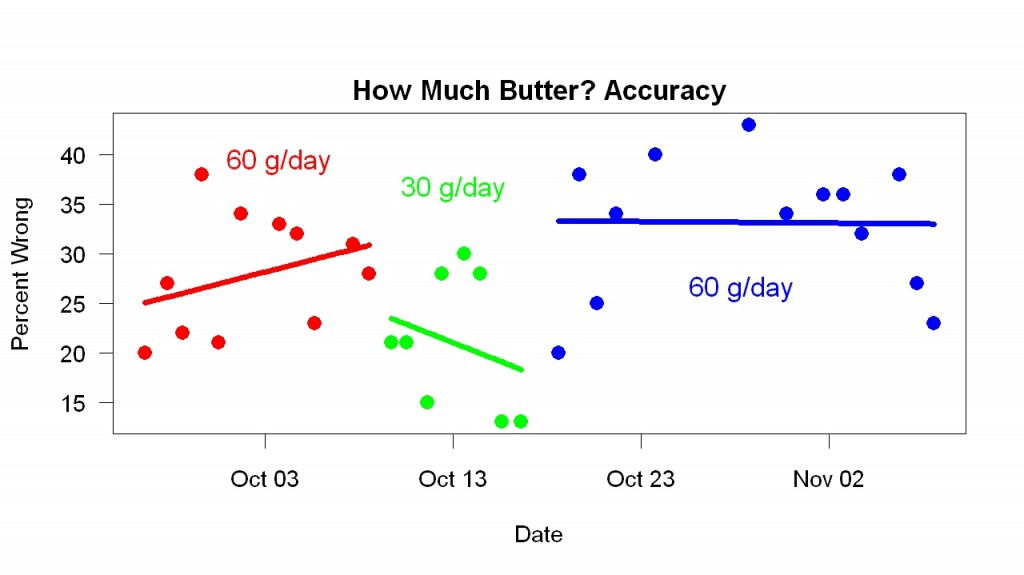

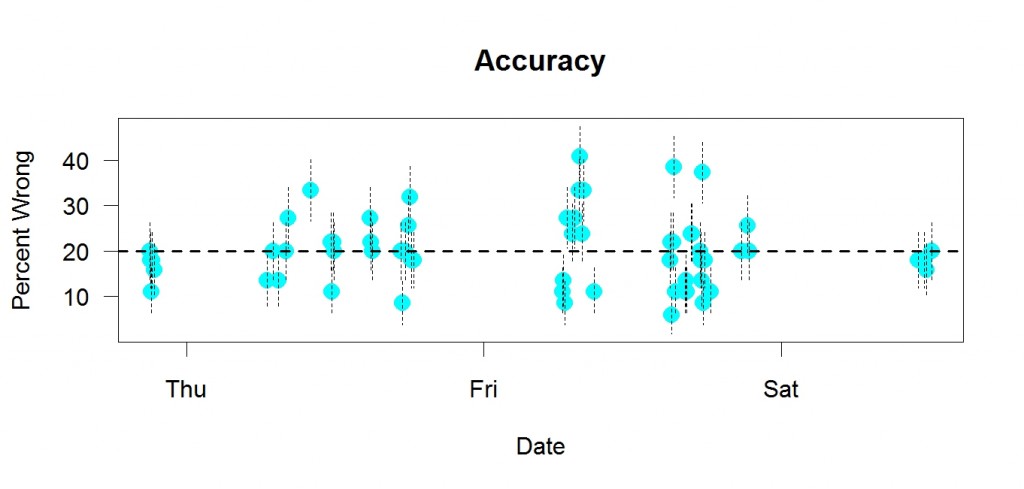

The amount of butter also affected my error rate. Less butter, less errors:

Comparing the 30 g/day results with the combination of earlier and later 60 g/day results, t = 3, p = 0.006.

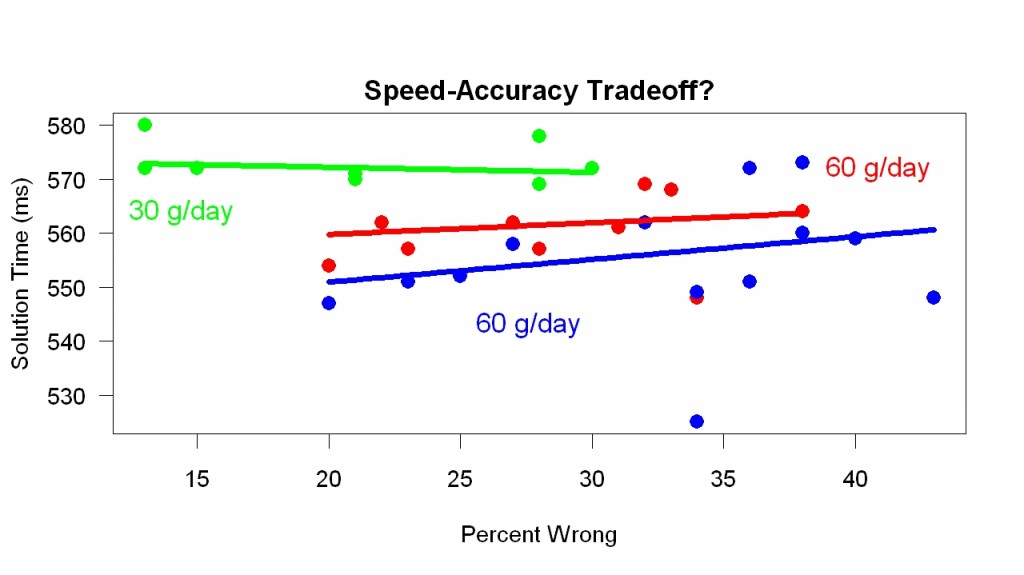

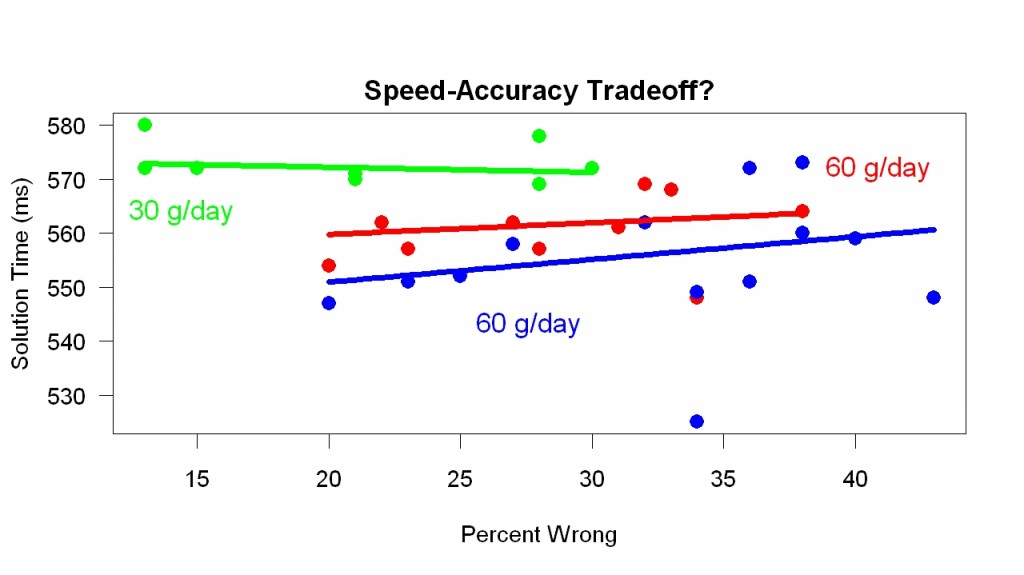

The change in error rates raised the possibility that the speed changes were due to movement along a speed-accuracy tradeoff function (rather than to genuine improvement, which would correspond to a shift in the function). To assess this idea, I plotted speed versus accuracy (each point a different day).

If differences between conditions were due to differences in speed-accuracy tradeoff, then the points for different days should lie along a single downward-sloping line. They don’t. They don’t lie along a single line. Within conditions, there was no sign of a speed-accuracy tradeoff (the fitted lines do not slope downward). If this is confusing, look at the points with accuracy values in the middle. Even when equated for accuracy, there are differences between the 30 g/day phase and the 60 g/day phases.

What did I learn?

1. How much butter is best. Before these results, I had no reason to think 60 g/day was better than 30 g/day. Now I do.

2. Speed of change. Environmental changes may take months or years to have their full effect. Something that makes your bones stronger may take months or years to be fully effective. Here, however, changes in butter intake seemed to have their full effect within a day. I noticed the same speed of change with pork fat and sleep: How much pork fat I ate during a single day affected my sleep that night (and only that night). With omega-3, the changes were somewhat slower. A day without it made little difference. You can go weeks without Vitamin C before you get scurvy. Because of the speed of the butter change, in the future I can do better balanced experiments that change conditions more often.

3. Better experimental design. An experiment that compares 60 g/day and 0 g/day probably varies many things besides butter consumption (e.g., preparing the butter to eat it). An experiment that compares 60 g/day and 30 g/day is less confounded. When I ate less butter, I ate more of other food. Compared to a 60 g/0 g experiment, this experiment (60 g/30 g) has less variation in other food. Another sort of experiment, neither better nor worse, would vary type of fat rather than amount. For example, replace 30 g of butter with 30 g of olive oil. Because the effect of eliminating 30 g/day of butter was clear, replacement experiments become more interesting — 30 g/day olive oil is more plausible as a sustainable and healthy amount than 60 g/day.

4. Generality. This experiment used cheaper butter and took place in a different context than the original discovery. I discovered the effect of butter using Straus Family Creamery butter. “One of the top premium butters in America, ” says its website, quoting Food & Wine magazine This experiment used a cheaper less-lauded butter (Land O’Lakes). Likewise, I discovered the effect in Berkeley. I did this experiment in Beijing. My Beijing life differs in a thousand ways from my Berkeley life.

The results suggest the value of self-experimentation, of course. Self-experimentation made this study much easier. But other things also mattered.

First, reaction-time methodology. In the 1960s my friend and co-author Saul Sternberg, a professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, introduced better-designed reaction-time experiments to study cognition. They turned out to be far more sensitive than the usual methods, which involved measuring percent correct. (Saul’s methodological advice about these experiments.)

Second, personal science (science done to help yourself). I benefited from the results. Normal science is part of a job. The self-experimentation described in books was mostly (or entirely) done as part of a job. Before I collected this data, I put considerable work into these measurements. I discovered the effect of butter in an unusual way (measuring myself day after day), I tried a variety of tasks (I started by measuring balance), I refined the data analysis, and so on. Because I benefited personally, this was easy.

Third, technological advances. Twenty years ago this experiment would have been more difficult. I collected this data outside of a lab using cheap equipment (a Thinkpad laptop running Windows XP). I collected and analyzed the data with R (free). A smart high school student could do what I did.

There is more to learn. The outlier in the speed data (one day was unusually fast) means there can be considerable improvement for a reason I don’t understand.

The Genomera Buttermind Experiment.

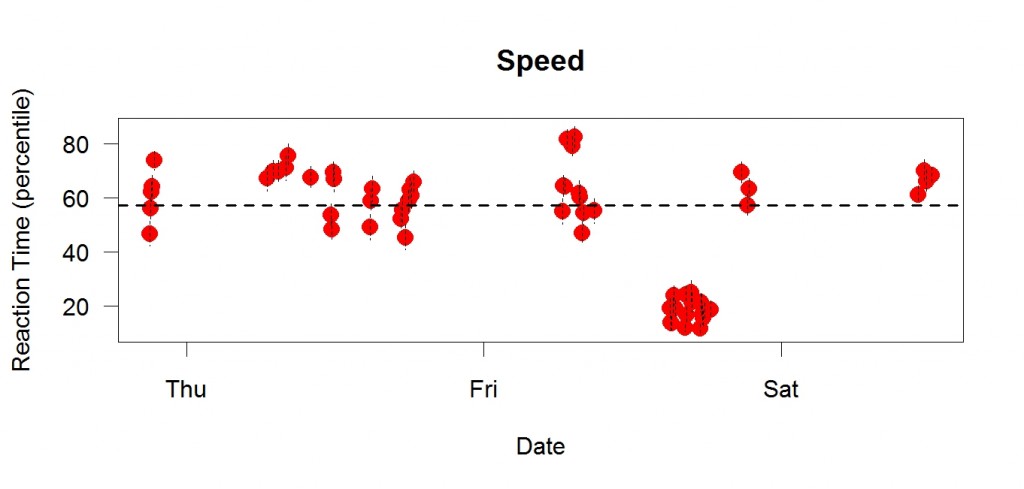

This is me a few days ago. I did a choice reaction time task many times. Each dot is a session with enough trials to supply 32 correct answers.The y axis is in “percentile” units, meaning speed relative to recent performance. If my speed was at the average of recent performance, the percentile would be 50, for example. Higher percentiles = better performance = faster (shorter reaction time). Each point is a mean; the vertical bars are standard errors. The dotted line is the median of the means.

This is me a few days ago. I did a choice reaction time task many times. Each dot is a session with enough trials to supply 32 correct answers.The y axis is in “percentile” units, meaning speed relative to recent performance. If my speed was at the average of recent performance, the percentile would be 50, for example. Higher percentiles = better performance = faster (shorter reaction time). Each point is a mean; the vertical bars are standard errors. The dotted line is the median of the means.

The graph shows that when I switched to 30 g/day, I became slower. When I resumed 60 g/day, I became faster. Comparing the 30 g/day results with the combination of earlier and later 60 g/day results, t = 6, p = 0.000001.

The graph shows that when I switched to 30 g/day, I became slower. When I resumed 60 g/day, I became faster. Comparing the 30 g/day results with the combination of earlier and later 60 g/day results, t = 6, p = 0.000001.