This sidebar appeared in an article about self-tracking (only for subscribers) by James Kennedy, who works at The Future Laboratory in London. The top photo is at a market near my apartment. Below that are photos of my sleep records, my morning-faces setup, my butter, and my kombucha brewing jars. Back then I was comparing three amounts of sugar (each jar a different amount). Now I’m comparing green tea/black tea ratios.

This sidebar appeared in an article about self-tracking (only for subscribers) by James Kennedy, who works at The Future Laboratory in London. The top photo is at a market near my apartment. Below that are photos of my sleep records, my morning-faces setup, my butter, and my kombucha brewing jars. Back then I was comparing three amounts of sugar (each jar a different amount). Now I’m comparing green tea/black tea ratios.

Category: butter

Assorted Links

- Benefits of fermented wheat germ extract

- Why Anthropogenic Global Warming (AGW) is unlikely. A list of AGW-associated “miracles”. Some of my favorites: “Unique among all sciences, climatology develops yet finds no surprises whatsoever, apart from when it’s worse than we thought” and “AGW is a grave threat to humanity, yet it can take the backseat when AGWers have to score their petty points (such as not sharing their data with the “wrong” people)” and “Having won an Oscar, a Nobel Prize and innumerable awards, having occupied more or less every audio or video broadcast for years, having had the run of more or less every newspaper for the same length of time, suddenly AGW leaders declare they’re not “great communicators” and blame this for the generally high levels of skepticism.”

- Denmark has started to tax butter. “To discourage poor eating habits and raise revenue.”

- Life-saving personal science: Mom figures out cause of daughter’s problems. “One spring night in 2002, she stumbled upon an old photocopy of a 1991 Los Angeles Times article that described a young girl whose condition had uncanny parallels with [her daughter’s].”

Thanks to David Cramer.

A Happy Reader Writes: Yogurt, Butter, Flaxseed Oil

A reader of this blog started taking flaxseed oil, half a stick of butter daily, and yogurt. “This works wonders,” he wrote me. “It feels like lubricant to the mind.”

The Evolution of Lactose Tolerance and My Butter Discoveries

From a BBC documentary called Are We Still Evolving? I learned that after the development of farming there was intense selection in Europe for “lactose tolerance” — meaning the ability to digest lactose as an adult, which requires the enzyme lactase. (The technical name is lactase persistence.) The necessary gene spread rapidly. Now most Europeans have the gene. In Ireland almost everyone has the gene. Mark Thomas, an evolutionary geneticist interviewed on the show, who does research on lactose tolerance, said this:

It’s probably the most advantageous characteristic that Europeans have evolved in the last 30,000 years.. . . The advantage that’s been measured is just incredible, absolutely incredible, how big an advantage it was for these early farmers in Europe.

“Why would drinking milk into adulthood be so strongly selected for?” asked Alice Roberts, the presenter. Thomas replied,

Milk has got lots of energy in it, it’s very nutrient dense, it’s got lots of other goodies, like various vitamins, calcium, and so on. Also, it’s a relatively clean fluid, so it’s much better than drinking stream water or river water or well water or something like that. Another advantage is if you’re growing crops you have a boom and bust in terms of the food supply.

Not a word about butterfat — “lots of energy” is true of all fats. The rapid spread, the “incredible” advantage, suggests that milk supplied something resembling a necessary nutrient. As if everyone had been suffering from scurvy and the new gene allowed them to eat citrus — something like that. Such a gene would spread rapidly.

Does milk supply a necessary nutrient? My results suggest that butter — half a stick (60 g)/day — provides two clear benefits: 1. Better brain function. 2. Less risk of heart disease (probably). As far as I can tell, roughly everyone in America would get these benefits because their diets now lack enough of whatever it is. Both benefits reflect invisible problems. Like everyone else, I had no idea my brain function could be substantially improved and had no idea of my rate of progression (narrowing of arteries) toward atherosclerosis. Only because of unusual tests (the arithmetic test and a “heart scan”) did I notice sudden large improvements when I started eating lots of butter — what you’d expected from addition of a missing necessary nutrient. This explains why Thomas and almost everyone else is unaware of these benefits.

Keep in mind that before I started eating butter, I already ate a high-fat low-carbohydrate diet. Yet I wasn’t getting enough of something in butter. I already ate lots of pork fat. Perhaps the saturated fat in butter is better digested than the saturated fat in pork. Or perhaps the fat profile is better.

If lactose tolerance is so helpful, why are most Asians lactose intolerant? My work suggests two answers: 1. Yogurt. Long ago, Asians ate lots of yogurt. I know the Mongols did. There are present-day indications of this. The Chinese appreciate the value of yogurt more than Americans. Yogurt is more common in Chinese supermarkets than American ones. Yogurt makers are better and more common in China than Europe and America. Lots of Chinese make their own yogurt; as far as I can tell, home yogurt making is more popular in China than America. You can buy a cheap good yogurt maker many places in Beijing, unlike San Francisco. Yogurt provided butterfat. 2. Pork. The Chinese, of course, eat far more pork than Europeans. Unlike cows, pigs supply a cut with a large amount of fat: pork belly. I found it easy to get plenty of pork belly in China and eat it as the main course. Difficulty getting pork belly in the Bay Area is what pushed me to eat butter. This view predicts that European farmers raised more cows than pigs.

Anyway, to summarize, the great advantage conferred by lactose tolerance suggests the great value of something in milk if you eat a European-farmer-like diet. My work supports this; it suggests the crucial ingredient is butterfat. Which many Americans carefully avoid!

Note: The danger posed by the high level of AGEs (advanced glycation endproducts) in butter I don’t know about — but of course this danger has nothing to do with why lactose tolerance was so beneficial. My experience so far (the heart-scan improvement) suggests that that ordinary butter is not “artery-constricting”. Presumably AGEs are formed when milk is pasteurized so I would prefer to eat unpasteurized butter.

Science in Action: Why Energetic?

Last night I slept unusually well, waking up more rested and with more energy than usual. I slept longer than usual: 7.0 hours versus my usual 5.1 hours (median of the previous 20 days). My rating of how rested I felt was 99.2% (that is, 99.2% of fully rested); the median of the previous 20 days is 98.8%. Because the maximum is 100%, this is really a comparison of 0.8% (this morning) with 1.2% (previous mornings); and the comparison is not adjusted for the number of times I stood on one leg to exhaustion, which improves this rating. During the previous 20 days I often stood on one leg to exhaustion six times; yesterday I only did it four times. Above all, I felt more energy in the morning. This was obvious. I have just started to measure this. At 8 am and 9 am, I rate my energy on a 0-100 scale where 50 = neither sluggish nor energetic/energized, 60 = slightly energetic/energized, 70 = somewhat energetic/energized, and 75 = energetic/energized. My ratings this morning were 73 (8 am) and 74 (9 am). The median of my 9 previous ratings is 62. The energy improvement (73/74 vs 62) is why I am curious. I would like to feel this way every morning.

What caused it? I had not exercised the previous day. My room was no darker than usual. My flaxseed oil intake was no different than usual. I had not eaten more pork fat than usual. However, four things had been different than usual:

1. 2 tablespoons of butter at lunch. In addition to my usual 4 tablespoons per day.

2. 0.5-1 tablespoons of butter at bedtime. Again, in addition the usual 4.

3. 1 tablespoon (15 g) coconut butter at bedtime. Part of a longer study of the effect of coconut butter. Gary Taubes suggested this. I had eaten 1 T coconut butter at bedtime 13 previous days. On the first of those 13 days, I had felt a lot more energetic than usual in the morning. On the remaining days, however, the improvement was less clear. I started measuring how energetic I felt in the morning to study this further. Last night was Friday night. On the previous two nights (Wednesday and Thursday) I had not eaten the coconut butter. Maybe absence of coconut butter followed by resumption of coconut butter is the cause.

4. Fresh air and ambient noise. Following a friend’s suggestion, I opened one of my bedroom windows.

My first question is whether the improvement is repeatable. If so, I will start to vary these four factors.

Assorted Links

- Top uses of natto

- I found Three Cups of Tea (about establishing schools in Pakistan) unreadable. Whereas I want to learn more about Pratham schools.

- Stagnation in claims about climate-change skeptics (such as me)

- “A 51-year-old physician colleague who looked the picture of health—no cardiovascular risks, a marathon runner who had exercised vigorously each day for 30 years—had just flunked a calcium screening scan of his heart” (link). After I started doing the “wrong” thing (eat half a stick of butter per day) my calcium screening score substantially improved.

- more about scientific fraud at Duke University

Ancient Wisdom: Butter is Brain Food

In Ayurvedic medicine (Indian traditional medicine), ghee, a type of clarified butter, is believed to improve brain function. For example, “Vedic medicine extols the virtues of ghee and dairy for the brain.” I found that butter improved how fast I could do arithmetic.

The Buttermind Experiment

In August, at a Quantified Self meeting in San Jose, I told how butter apparently improved my brain function. When I started eating a half-stick of butter every day, I suddenly got faster at arithmetic. During the question period, Greg Biggers of genomera.com proposed a study to see if what I’d found was true for other people.

Eri Gentry, also of genomera.com, organized an experiment to measure the effect of butter and coconut oil on arithmetic speed. Forty-five people signed up. The experiment lasted three weeks (October 23-November 12). On each day of the experiment, the participants took an online arithmetic test that resembled mine.

The participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: Butter, Coconut Oil, or Neither. The three weeks were divided into three one-week phases. During Phase 1 (baseline), the participants ate normally. During Phase 2 (treatment), the Butter participants added 4 tablespoons of butter (half a stick of butter) each day to their usual diet. The Coconut-Oil participants added 4 tablespoons of coconut oil each day to their usual diet. The Neither participants continued to eat normally. During Phase 3 (baseline), all participants ate normally.

After the experiment was finished. Eri reduced the data set to participants who had done at least 10 days of testing. Then she made the data available. I wanted to compute difference scores (Phase 2 MINUS average of Phases 1 and 3) so I eliminated someone who had no Phase 3 data. I also eliminated four days where the treatment was wrong (e.g., in the sequence N N N N N B B N N B, where N = Neither and B = Butter, I eliminated the final Butter day). That left 27 participants and a total of 443 days of data.

Because the scores on individual problems were close to symmetric on a log scale, I worked with log solution times. I computed a mean for each day for each participant and then a mean for each phase for each participant.

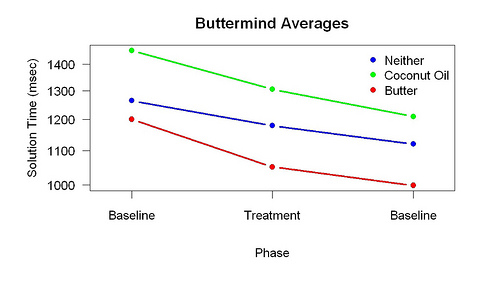

This figure shows the means for each phase and group. The downward slopes show the effect of practice. The separation between the lines shows that individual differences are large. (There was no reliable difference between the three groups during Phase 1.)

This figure shows the means for each phase and group. The downward slopes show the effect of practice. The separation between the lines shows that individual differences are large. (There was no reliable difference between the three groups during Phase 1.)

The point of the baseline/treatment/baseline design is allow for a large practice effect and large individual differences. It allows a treatment effect to be computed for each participant by computing a difference score: Phase 2 MINUS average of Phases 1 and 3. The average of Phases 1 and 3 estimates what the results would be if the treatment made no difference.

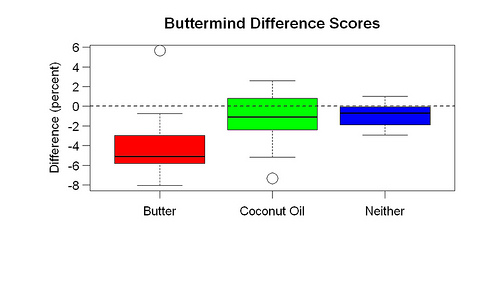

This graph shows the difference scores. There are clear differences by group. A Wilcoxon test comparing the Butter and Neither groups gives one-tailed p = 0.006.

The results support my idea that butter improves brain function. They also suggest that coconut oil does not. In the next post I’ll discuss what else I learned from this experiment.

Food For Thought

A perfectly good Economist article about food and brain function includes the following:

Many studies suggest that diets which are rich in trans- and saturated fatty acids, such as those containing a lot of deep-fried foods and butter, have bad effects on cognition. Rodents put on such diets show declines in cognitive performance within weeks.

Whereas I found butter improved my cognitive performance within a day. And pork fat improved my sleep within a day. On the other hand, I wouldn’t be surprised if foods deep-fried in plant oils, such as corn oil, are bad for the brain.

Why Small Change = Big Deal (revised)

Last week a journalist asked me why the 5% improvement in arithmetic speed produced by butter was important. In an earlier post I said I’d given a poor answer. A few days later I figured out what I should have said. The article was delayed, it turned out, so there was time to use my new strategy. I answered the question like this:

I was excited by this discovery because it was so big and unexpected. Someone once found a correlation between IQ and reaction time. The higher your IQ, the faster your reaction time. I don’t know what the exact function was but a decrease of 30 milliseconds might correspond to 10 more IQ points. I felt a little bit smarter. It was so unexpected because hardly anyone was going around saying butter is good for you — and thousands of people were saying it is bad for you. The only ones saying butter is good for you were the followers of Weston Price, and they had almost no evidence for what they were saying. Compared to their evidence, my evidence was crystal clear. Among mainstream nutritionists, butter is universally scorned. Yet my data suggested exactly the opposite — that it had a large amount of an important nutrient I wasn’t getting enough of. If mainstream nutrition advice could be so wrong, it would have big implications for what we eat. Maybe other things we are constantly told about what to eat are also wrong.

I discovered this big effect of butter by substituting butter for pork fat. So the reason butter was so helpful wasn’t anything as simple as animal fat is food for us. I ate plenty of animal fat before I started eating lots of butter. The reason was something more specific.