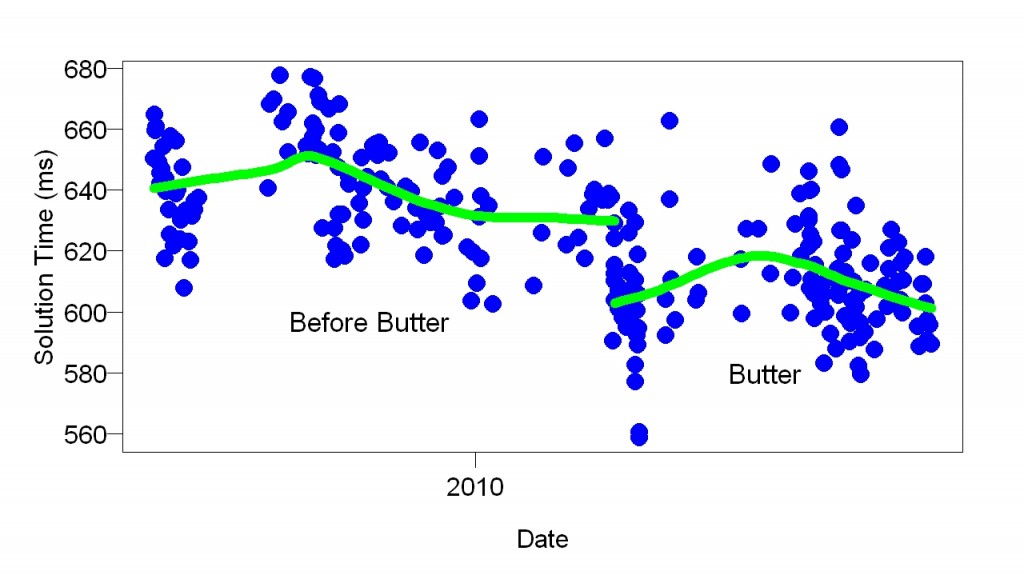

Eating a half-stick of butter (60 g) every day apparently improved how fast I can do simple arithmetic problems (e.g., 7-5, 3+1). I improved about 5% — from 630 to 600 msec per problem. My scores had been at 630 msec for months. They suddenly dropped.

A reporter said to me that a 5% improvement isn’t much. You couldn’t notice it. Why did this matter?

I did not reply “ what good is a newborn baby?” I said it mattered for three reasons:

1. You cannot easily produce such an improvement. I was already doing very well. For example, I had already lowered my scores a lot via omega-3. Imagine the world record for the 100 meter dash suddenly dropping 5% due to eating something you can find in a supermarket.

2. A 5% improvement is just the beginning. There is room for optimization — better dosage, better timing of taking the butter, and so on.

3. The brain is a mirror of the rest of the body. Learning the best diet for the brain, at least in terms of fat, will help us learn the best diet for the rest of the body, just as learning what house current is best for one electrical appliance is a guide to what other electrical appliances are designed for. They’re all designed to work with the same house current.

Alas, this is not just a poor answer, it’s what I actually said. I give myself a C+. Reason 1 is almost gibberish. Reason 2 is technocratic. A good answer is more emotional. Reason 3 is okay, if not very clear.

At Berkeley I knew a student who had transferred from a junior college. He is/was black. He had probably gotten into Berkeley because Berkeley administrators wanted to admit more black students. He complained one day that he got C’s on his essays even though “all the words were spelled correctly.” It was frustrating, he said. I am in a similar situation here. My answer is poor but I cannot easily do better.