One of my students grew up and went to high school in Nanjing, population 8 million. Her acceptance to Tsinghua was such a big deal that when her acceptance letter reached the local post office they called to tell her. The post office also alerted journalists. When the letter was delivered to her house, there were about 20 journalists on hand. One of them, from a TV station, asked her to say something to those who failed.

Category: China

The Physical Spacing Effect: New Way to Learn Chinese Works Shockingly Well

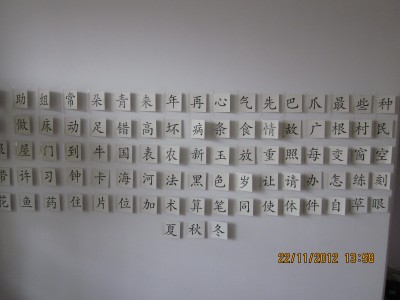

Two years ago I taped a bunch of Chinese flash cards (Chinese character on one side, English meaning on the other) to my living room wall (shown above). I’ll study them in off moments, I thought. I didn’t. It was embarrassing when guests pointed to a card and said, “What’s that?” But not embarrassing enough.

A few weeks ago, I can’t remember why, I decided to test myself: how many do I know? About 20%. I’ll try to learn more, I thought. I was astonished how fast I learned the rest. It took little time and almost no effort. I didn’t need “study sessions”. I glanced at the array now and then, looked for cards I didn’t know yet, and flipped them to find out the answer. After a few days I knew all of them.

I had been using conventional methods (flash cards studied in ordinary ways, Anki, Skritter) and an unconventional method (treadmill study) to learn this material for years. In spite of spending more than a hundred hours on each method, I had never gotten very far. I might get to 500 characters and backslide due to lack of study. Treadmill walking while studying made studying much more pleasant, but I found I would still prefer to watch TV rather than study Chinese. Maybe part of the problem was too many days skipped. After you skip four days, for example, you have a discouragingly large number of cards to review. Plainly these methods work for others. They didn’t work for me.

After my success with the two-year-old cards, I put up another array (8 x 13). I already knew about 40% of them. I learned the rest in a day or so. Then I put up a 10 x 12 array. I tested myself on them one morning. I knew 30 of them. I studied them during the day for maybe 30 minutes in little pieces throughout the day. The next morning I tested myself again (about 12 hours from the last time I had studied them). Now I knew 105 — I had learned 75 in one day, almost effortlessly. That day I studied for a few minutes. The next morning I tested myself again. Now I knew all but one of them.

I did not notice any facilitation of learning when I studied flash cards while walking around. In that case, unlike this one, (a) they were in roughly the same position relative to my body and (b) had no consistent physical location. I noticed the same facilitation of learning during a Chinese lesson in a cafe. I was having trouble remembering three Chinese words (e.g., the Chinese word that means graduate). I wrote each of them on a piece of paper with the English on one side and the Chinese on the other. I put the three pieces of paper at widely-separated places on the table. I studied them briefly, a few seconds each. That was enough. Five days later I still remember them (having used them a few times since then). This happened in a place (a cafe) with which I wasn’t familiar, unlike my living room. Maybe the general principle will be it is much easier to learn an association if it is in a new place.

It’s very early in my use of this method, but I doubt it’s a fluke. It connects with several things we (= psychology professors) already know. 1. The mnemonic device called the method of loci. You put things you want to learn in different places in a well-remembered landscape (e.g. different places in a building you know well). Usually the method is used to learn lists, such as the digits of pi or the order of cards in a deck. You place different items in the list in different places in the imagined place. Then you “walk” (in your imagination) through the imagined place. The method dates back to ancient Rome. 2. The power of interference. Thousands of experiments have shown that learning X makes it harder to learn similar Y. X and Y might be two lists, for example. The greater the similarity, the bigger the effect. What you learn on Monday makes it harder to learn stuff on Tuesday (proactive interference); what you learn on Tuesday makes it harder to remember what you learned on Monday (retroactive interference). To anyone familiar with these experiments, my discovery has a simple “explanation”: spatial interference. 3. Evolutionary plausibility. The study of printed materials (e.g., books) is so recent it is hard to imagine our brain has evolved to make it easy. In contrast, thousands and millions of years ago we had to learn about things in different places. Learning about food and danger in different places was especially important. When language arrived, the necessary learning (at first, attaching names to objects) is quite similar to my learning because the named objects were in different places. The study of vitamins and to some extent my work (especially the power of morning faces) show how hard it can be to figure out what we need for our brains and bodies to work well. How non-intuitive the answers may be.

These results suggest a new mnemonic device: Stand in front of an empty wall and imagine on the wall the associations you want to learn, each association in a different place like flashcards. This is a fast way of putting each association in a different place.

Assorted Links

- chocolate: what is the best dose?

- tasting sugar water improves self-control

- The Beijing Interceptors.

- doctor complains about over-prescription of opiates. The author, a doctor named Susana Duncan, complains about several things, including “a system where symptoms are treated but the source of pain remains”. Treatment of symptoms rather than identification of causes is overwhelmingly true of the whole health care system, not just treatment of chronic pain. One example is depression. Anti-depressants do not reduce whatever caused the depression. Another example is high blood pressure. Blood-pressure-lowering drugs do nothing to eliminate what caused the high blood pressure. Duncan was once science editor of New York magazine, which may have something to do with her ability to cogently criticize the system.

- A British surgeon performs hundreds of unnecessary operations before being caught.

Thanks to Edward Jay Epstein, Bryan Castañeda, Paul Nash, Jay Barnes and Dave Lull.

Positive Psychology Talk by Martin Seligman at Tsinghua University

Here at Tsinghua University, the Second Annual Chinese International Conference on Positive Psychology has just begun. The first speaker was Martin Seligman, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and former president of the American Psychological Association (the main professional group of American psychologists). Seligman is more responsible for the Positive Psychology movement than anyone else. Here are some things I liked and disliked about his talk.

Likes:

1. Countries, such as England, have started to measure well-being in big frequent surveys (e.g., 2000 people every month) and some politicians, such as David Cameron, have vowed to increase well-being as measured by these surveys. This is a vast improvement over trying to increase how much money people make. The more common and popular and publicized this assessment becomes — this went unsaid — the more powerful psychologists will become, at the expense of economists. Seligman showed a measure of well-being for several European countries. Denmark was highest, Portugal lowest. His next slide showed the overall result of the same survey for China: 11.83%. However, by then I had forgotten the numerical scores on the preceding graph so I couldn’t say where this score put China.

2. Work by Angela Duckworth, another Penn professor, shows that “GRIT” (which means something like perseverance) is a much better predictor of school success than IQ. This work was mentioned in only one slide so I can’t elaborate. I had already heard about this work from Paul Tough in a talk about his new book.

3. Teaching school children something about positive psychology (it was unclear what) raised their grades a bit.

Dislikes:

1. Three years ago, Seligman got $125 million from the US Army to reduce suicides, depression, etc. (At the birth of the positive psychology movement, Seligman proclaimed that psychologists spent too much time studying suicide, depression, etc.) I don’t mind the grant. What bothered me was a slide used to illustrate the results of an experiment. I couldn’t understand it. The experiment seems to have had two groups. The results from each group appeared to be on different graphs (making comparison difficult, of course).

2. Why does a measure of well-being not include health? This wasn’t explained.

3. Seligman said that a person’s level of happiness was “genetically determined” and therefore was difficult or impossible to change. (He put his own happiness in “the bottom 50%”.) Good grief. I’ve blogged several times about how the fact that something is “genetically-determined” doesn’t mean it cannot be profoundly changed by the environment. Quite a misunderstanding by an APA president and Penn professor.

4. He mentioned a few studies that showed optimism (or lack of it) was a risk factor for heart disease after you adjust for the traditional risk factors (smoking, exercise, etc.). There is a whole school of “social epidemiology” that has shown the importance of stuff like where you are in the social hierarchy for heart disease. It’s at least 30 years old. Seligman appeared unaware of this. If you’re going to talk about heart disease epidemiology and claim to find new risk factors, at least know the basics.

5. Seligman said that China had “a good safety net.” People in China save a large fraction of their income at least partly because they are afraid of catastrophic medical costs. Poor people in China, when they get seriously sick, come to Beijing or Shanghai for treatment, perhaps because they don’t trust their local doctor (or the local doctor’s treatment failed). In Beijing or Shanghai, they are forced to pay enormous sums (e.g., half their life’s savings) for treatment. That’s the opposite of a good safety net.

6. Given the attention and resources and age of the Positive Psychology movement, the talk seemed short on new ways to make people better off. There was an experiment with school children where the main point appeared to be their grades improved a bit. A measure of how they treat each other also improved a bit. (Marilyn Watson, the wife of a Berkeley psychology professor, was doing a study about getting school kids to treat each other better long before the Positive Psychology movement.) There was an experiment with the U.S. Army I couldn’t understand. That’s it, in a 90-minute talk. At the beginning of his talk Seligman said he was going to tell us things “your grandmother didn’t know.” I can’t say he did that.

A Theft in China

A friend of mine was at a KFC in Beijing. She returned from the bathroom to find her purse was gone. She called the manager. The police came in 15 minutes. At the police station, she saw security footage, which showed that her purse had been taken by an 11-year-old girl. “Heart-breaking,” said my friend.

Two Dimensions of Economic Growth: GDP and Useful Knowledge

Ecologists understand the exploit/explore distinction. When an animal looks for food, it can either exploit (use previous knowledge of where food is) or explore (try to learn more about where food is). With ants, the difference is visible. Trail of ants to a food source: exploit. Solitary wandering ant: explore. With other animals, the difference is more subtle. You might think that when a rat presses a bar for food, that is pure exploitation. However, my colleagues and I found that when expectation of food was lower, there was more variation — more exploration — in how the rat pressed the bar. In a wide range of domains (genetics, business), less expectation of reward leads to more exploration. In business, this is a common observation. For example, yesterday I read an article about the Washington Post that said its leaders failed to explore enough because they had a false sense of security provide by their Kaplan branch. “Thanks to Kaplan, the Post Company felt less pressure to make hard strategic choices—and less pressure to venture in new directions,” wrote Sarah Ellison.

Striking the right balance between exploitation and exploration is crucial. If an animal exploits too much, it will starve when its supply of food runs out. If it explores too much, it will starve right away. Every instance of collapse in Jared Diamond’s Collapse: How Socieities Choose to Fail or Succeed was plausibly due to too much exploitation, too little exploration (which Diamond, even though he is a biologist, fails to say). I’ve posted several times about my discovery that treadmill walking made studying Chinese more pleasant. I believe walking creates a thirst for dry knowledge. My evolutionary explanation is that this pushed prehistoric humans to explore more.

I have never heard an economist make this point: the need for proper balance between exploit and explore. It is relevant in a large fraction of discussions about how to spend money. For example, yesterday I listened to the latest EconTalk podcast, a debate between Bob Frank and Russ Roberts about whether it would be a good idea for the American government to spend $2 trillion on infrastructure projects (fix bridges, etc.). Frank said it would create jobs, and so on — the usual argument. Roberts said if fixing bridges was such a good idea, why hadn’t this choice already been made? Roberts could have said, but didn’t, that massive government shovel-ready expenditures, such as $2 trillion spent on infrastructure repair, inevitably push the exploit/explore balance toward exploit, which is dangerous. This is an argument against all Keynesian stimulus-type spending. I have heard countless arguments about such spending. I have never heard it made. If you want examples of how the American economy suffers from a profound lack of useful new ideas, look at health care. As far as I know, there are no recorded instances of a society dying because of too much exploration. The problem is always too much exploitation. People at the top — with a tiny number of exceptions, such as the Basques — overestimate the stability of their position. At the end of The Economy of Cities, Jane Jacobs says that if a spaceship landed on Earth, she would want to know how their civilization avoided overexploitation. When societies exploit too much and explore too little, said Jacobs, problems (in our society, problems such as obesity, autism, autoimmune disease, etc.) stack up unsolved. Today is China’s birthday. Due to overexploitation, I believe China is in even worse economic shape than America. Ron Unz, whom I respect, misses this.

My broad point is that a lot of economic thinking, especially about growth and development, is one-dimensional (measuring primarily growth of previously existing goods and services — exploitation) when it should be two-dimensional (measuring both (a) growth of existing stuff and (b) creation of new goods and services). Exploration (successful exploration) is inevitably tiny compared to exploitation, but it is crucial there be enough of it. If there is a textbook that makes this point, I haven’t seen it. An example of getting it right is Hugh Sinclair’s excellent new book Confessions of a Microfinance Heretic (copy sent me by publisher) that debunks microcredit. Leaving aside the very high interest rates, the use of microcredit loans to buy TVs, and so on, microcredit is still a bad idea because the money is, at best, used for a business that copies an existing business. (The higher the interest rate, the less risk a loan recipient dares take.) When a new business copies an already-existing business, you are taking an existing pie (e.g., demand for milk, if the loan has been used to buy a cow and sell its milk) and dividing it into one more piece. The pie does not get bigger. As Sinclair says, the notion that dividing existing pies into more pieces will “create a poverty-free world” is, uh, not worthy of a Nobel Prize.

Sure, it’s hard to measure growth of useful knowledge. (It is perfectly possible for a company to waste its entire R&D budget.) However, I am quite sure that realism does better than make-believe — and the notion that growth of GDP is a satisfactory metric of economic growth is make-believe. If you’ve ever been sick, or gone to college, and have a sense of history, you will have noticed the profound stagnation in two unavoidable sectors (health care and education) of our economy. That are growing really fast.

Assorted Links

- Yale cancels China year-abroad program. One reason is that students in Beijing (at Peking University, one of the best universities in the country) learned less Chinese than students at Yale.

- European plagiarism epidemic. “More than a third of a new book for law students on how to write papers properly was plagiarised . . . The authors vowed to find the culprits.”

- Penkowa for Dummies. Complicated scientific fraud.

- Self-tracking difficulties: a fickle and too-demanding exercise tracker. I try to walk 60 minutes/day. It’s easy to track.

Thanks to Anne Weiss.

What to Do in Beijing: My Suggestions

Because Tyler Cowen is going to Beijing, I made a list of suggestions:

1. Don’t go to the Great Wall. It’s a long drive. I preferred to see it on the Today Show. The only interesting bit was a guy who sat in a chair on the path to the wall and charged 30 cents to go further. We paid the 30 cents but in retrospect I wish we hadn’t.

2. Visit some of the many “markets” that consist of a building full of tiny booths. There are markets devoted to cameras, jewelry, clothes, electronics, furniture, etc. There can be more choice of furniture in one building (say, 100 manufacturers) than exists in the entire Bay Area. Along similar lines there is a whole neighborhood full of tea sellers — if you like tea.

3. Peking duck is a good dish but I cannot tell the difference between the better restaurants serving it. So don’t go out of your way to go to an especially good place. I usually go to Quanjude which has a branch very near my school (Tsinghua).

4. Middle 8 is a very good restaurant (in Haidian and Chao Yang).

5. Din Tai Fung is a very good dumpling restaurant. It is a big international Taiwanese chain. So it isn’t even mainland Chinese food exactly.

6. There are grilled chicken wing restaurants near the west gates of both Peking University and Tsinghua University. I don’t know their names but they are very good. Popular with students.

7. I have never found a nice place in Beijing to walk. Even in parks there is a lack of shade.

8. In my neighborhood (Wudaokou) there are excellent Korean restaurants.

Feel free to leave your suggestions in the comments.

Assorted Links

- Are the Boston Red Sox malnourished? Paul Jaminet looks at the connection between poor health of the Boston Red Sox and the dietary advice they were given.

- Cognitive benefits of chewing gum. “Chewing gum was associated with greater alertness and a more positive mood. Reaction times were quicker in the gum condition, and this effect became bigger as the task became more difficult.”

- Dave Asprey and Quantified Self. “He claims to have jacked up his IQ by 40 points.”

- “Why is this country called China in English?” I asked a Tsinghua student. “It was a source of china,” she said. She was more right than she could have known. The world’s oldest pottery has been found in China. (Via Melissa McEwen.) Given this head start, it’s no surprise that for a long time China had a monopoly on really hard pottery, called bone china or porcelain. It was the only source of this china.

How Difficult is Chinese? A Tsinghua Professor Complains

Recently there was a competition for Tsinghua civil engineering majors. Whose structure can support the most weight? And so on. At the end of the competition, a professor handed out prizes to the winners. After the awards ceremony, the professor who had handed out the awards said to a colleague, “I don’t like this job.” His colleague was surprised: What was so bad about handing out awards? The professor explained that the students’ names sometimes included characters so obscure that he didn’t know them. Which was embarrassing.