Is online teaching (e.g., MOOC) a big deal? In an essay (“Why Online Education Works”), Alex Tabarrok argues for the value of online education (meaning online lectures) compared to traditional lectures. A friend told me yesterday that MOOC was “a frontier of pedagogy”. No doubt online lectures will make lecture classes cheaper and more available. Lots of things have gone from scarce/expensive to common/cheap. With things whose effects we understand (e.g., combs), the result is straightforward: more people benefit. With things whose effects we don’t understand, the results are less predictable. Did the spread of sugar help us? Hard to say. Did the spread of antibiotics help us? Hard to say. It may have helped sustain simplistic ideas about what causes disease (e.g., “acne is caused by bacteria”, “ulcers are caused by bacteria”) reducing effective innovation. Do we have a good idea of the effects of lectures (or their lack of effect), or a good theory of college education? I don’t think so. Could their spread help sustain simplistic ideas about education? Maybe.

As books spread, the teaching of reading increased. Everyone understood that books were useless if people couldn’t read. The introduction of PCs was accompanied by user interface improvements. This helped PCs become influential– not restricted to hobbyists. Will online education be accompanied by similar make-it-more-palatable changes? I have heard nothing about this. Their advocates seem to think the current system is fine and if it could only be available to more people…

Online lectures will make much difference only if the cost and quality of lectures is the weakest link in what strikes me as a process with many links. It would be a coincidence if the link that can be most easily strengthened turned out to be the weakest link. For example, is the cost of lectures the main thing driving up the cost of college? That would be wonderful if it were true, but I haven’t seen evidence that it’s true. At Berkeley, for example, there has been enormous growth in the administrator-to-faculty ratio.

Here are two arguments used to argue that online lectures are a big step forward:

It will help people in poor countries, like Zambia. There is a long history of people in rich countries misunderstanding people in poor countries. Several years ago I was in Guatemala. I heard about a school being built by a (rich country) religious group in a poor area. After two years, the American running it wanted to leave. No member of the community took it over. It disappeared. “Maybe they didn’t want a school,” said the graduate student who told me about it. Maybe few people in Zambia want online lecture classes. (I have no idea.) If so, the benefit will be small.

It will save labor. Each lecture will be viewed many more times. Saving labor is not always good. It is plausible that the growth of online lectures will mean fewer college professors. Colleges and universities are among the few places where people do research and almost the only places where they do unrestricted research. Most of the research is useless; a tiny fraction is enormously useful. At the moment, lectures subsidize research. By giving lectures, professors are allowed to do research. Fewer professors, less unrestricted research, less innovation. “Wasteful” lecturing might be labor we shouldn’t save.

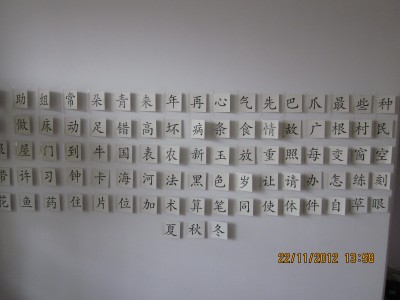

One thing I like about online classes is the possibility they will connect people who want to learn the same thing, like ordinary classes do. They can help each other, encourage each other, and so on. I have no doubts about the value of this. (I find language partners — I teach them English, they teach me Chinese — way more pleasant and helpful than tutors.)

At Berkeley, I tried to find good lecturers. With two exceptions (Tim White and Steve Glickman) I failed. Almost all lectures, even those by brilliant researchers, were dreary. (A shining exception by Robin Hanson.) They suffered from a lack of stories and a lack of emotion. (At Tsinghua, things are worse. A friend who majors in bioengineering told me that 80% of her teachers lecture by reading from the textbook.) The power of professors over students in some ways resembles the power of doctors over patients. Just as there is little pressure on doctors to understand disease (if antibiotics have bad effects, it doesn’t harm the doctor who prescribed them), there is little pressure on most professors — at least at the elite research universities that produce online lectures — to understand education. At Berkeley, many professors say they teach their undergraduate students “how to think” or “how to think critically”. In fact, they were teaching their students to imitate them. The simplest form of education. This is neither good nor bad — it depends on the student — but it is the opposite of sophisticated.

A few months ago I assigned my Tsinghua students (freshmen) to read 60 pages of The Man Who Would Be Queen by Michael Bailey, a book full of stories and emotion. Any 60 pages, their choice. No test, no written assignment, no grade. One student told me it was the first book in English she’d ever finished. It was so good she couldn’t stop reading. My assignment had changed real-life behavior: what my student read in her spare time. Maybe it changed her tolerance of homosexuality and the tolerance of those around her. My assignment (not a textbook or academic paper, not a fixed reading) and evaluation (none) differed from conventional college teaching. Experiences like this make me wonder what fraction of important learning during college happens due to lecture classes. (In my case, the fraction was zero.) If the fraction is low, it suggests that online learning won’t make much difference.