In 1995, I discovered that seeing faces in the morning raised my mood the next day. For example, seeing faces Monday morning improved my mood on Tuesday (but not Monday). Study of the effect suggested we have a face-sensitive oscillator that controls mood and sleep. The oscillator needs morning-face exposure to work properly — faces “push” the oscillator as you would push a swing. Long ago, this oscillator synchronized the mood and sleep of people who lived together. The synchronization helped them cooperate. It is much easier to work with a happy person than an unhappy person and, of course, much easier to work with someone awake than someone asleep.

My results suggested you need to see morning faces on the order of 30 minutes to get a big effect. The faces need to be similar to what you’d see in a conversation. Looking at people on the subway doesn’t count. Nowadays, as far as I can tell, hardly anyone gets the right input. In extreme cases, this causes depression, poor sleep, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorders. What else might it cause?

A friend, whom I’ll call Ben, recently told me something that sheds light on this. Three years ago he was a graduate student at Columbia. He lived in a basement apartment, with no sunlight. It was between semesters. He had no regular contact with anyone. He was depressed. Then things got worse: He became delusional. He started thinking that every conversation he heard was about him. “Everything I heard or saw was directed at me,” he said. There was a boiler in the room next to his apartment. He believed it was a nuclear reactor.

Although Ben was isolated in terms of seeing other people, he had non-visual contact with people online. He told them about his strange thoughts. Some thought he had a problem, some didn’t. Some thought he sounded mystical. He felt physical discomfort — a “pulling inside”. His heart seemed to be beating differently. He called his parents. They were so alarmed that they contacted someone they knew in New York. Eventually an ambulance arrived at Ben’s apartment and took him to a mental hospital. At the hospital, he told them he thought he was dead. After a day or so at the hospital, on a locked ward, he felt much better. However, he wasn’t allowed to leave for two weeks because the doctors didn’t know what was wrong with him.

After leaving the hospital he took a break from graduate school and went to stay with his parents. He saw a psychiatrist and was prescribed Risperdal (an antipsychotic) and Depakote (for mania).

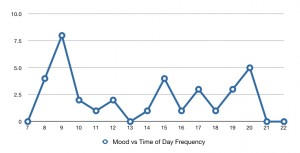

The pattern is okay during semester (when he sees others on campus), sick between semesters (when he doesn’t see others), okay in locked ward (when he sees others). Bipolar disorder sometimes includes delusions during mania, so the association of disordered internal rhythms and delusions is not new. But why should disordered internal rhythms cause delusions — in this case, paranoid ones? One possibility is that it is beneficial to be paranoid in the middle of the night. If someone wakes you up, you will wake up thinking they tried to wake you up, which will make you especially mad. The madder you are, the less likely they will do it again. I argued that the irritability associated with depression is beneficial in the middle of the night for just this reason: It protects sleep. If someone wakes you up you will get mad at them. This explanation predicts a circadian rhythm in paranoia, increasing in the evening. However, I’m not sure this explains why he thought a boiler in the next room was a nuclear reactor.