Kefir is much easier to make than yogurt because you ferment the milk at room temperature, once you have the starter culture. I’ve made it about ten times. The most recent batch was the easiest and best because I learned two things from the woman who gave me the starter:

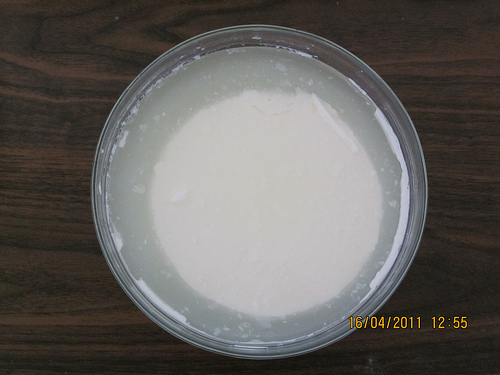

1. Ferment it until there is a line of separation. There eventually form a line of clear liquid between the curds (top) and the rest (bottom). This took about two days. In the past I didn’t know how long to wait.

2. After fermentation, separate the curds from the rest by putting it through a colander. This provides good separation. You drink the liquid, use the solids to make more kefir. In the past I tried to spoon out the kefir grains.

If I had to choose between kefir and yogurt I’d choose kefir. Not only is it easier to make but it is far more complex. Unlike yogurt, it’s a drink. I drink more often than I eat so there are more opportunities to consume it.

I suspect you can make kefir by putting store-bought kefir into ordinary milk. I haven’t tried this, however.