I recently got a flyer from my HMO. “Feel better soon . . . without antibiotics!” said the front page. “Antibiotics do not kill viruses” said the second page. Apparently the point of the flyer is to reduce antibiotic usage. I am surprised that doctors need protection from patients asking for antibiotics for viral diseases.

Antibiotic resistance is a problem, yes, but the bigger problem is how those who run our health care system ignore the immune system. Here are examples:

1. The historical solution to the problem of antibiotic resistance has been to develop new antibiotics. The problem has not stimulated research into how to strengthen the immune system. Here is a 1992 editorial in Science: “Mechanisms such as antibiotic control programs, better hygiene [= more handwashing], and synthesis of agents with improved antimicrobial activity need to be adopted in order to limit bacterial resistance.” Nothing about improving immune function. A 2012 World Health Organization report about the problem does not contain the word immune.

2. The idiocy of tonsillectomies. Forty years after researchers figured out that tonsils are part of the immune system, tonsillectomies remain common. Removing tonsils because of too many infections makes as much sense as removing part of the brain because of memory loss. I have never encountered a doctor who appears to understand this.

3. Epidemiologists have yet to systematically study what makes the immune system more or less powerful. For example, this epidemiology textbook does not contain the word immune. Nor does this review of 25 epidemiology textbooks.

4. A respected professor of pharmacology at the University College London named David Colquhoun left the following comment on this blog: “Talking of made up theories, the corniest of all has to be “stimulating the immune system”. There is [not], and never has been, any evidence that it happens — it is the eternal mantra of every quack who is trying to sell you their own brand of implausible therapy.” Here is an example of the evidence he says doesn’t exist. Professor Colquhoun is a Fellow of the Royal Society.

5. I know very little about the immune system. I barely know what a T cell is. My job (psychology professor) has nothing to do with it. Yet I have come up with three ideas related to it: 1. Tonsillectomies are idiotic. 2. We need regular intake of microbes to be healthy — in part to stimulate the immune system. 3. We need exposure in small amounts to the germs around us for our immune systems to best protect us. (So it’s not obvious that outside of hospitals more handwashing is a good thing.) Only because these ideas are obvious (#1 and #3) or semi-obvious (#2) was someone as ignorant as me able to think of them. That one ignorant outsider thought of three of these things before the hundreds of thousands of health researchers did suggests how little they think about the immune system.

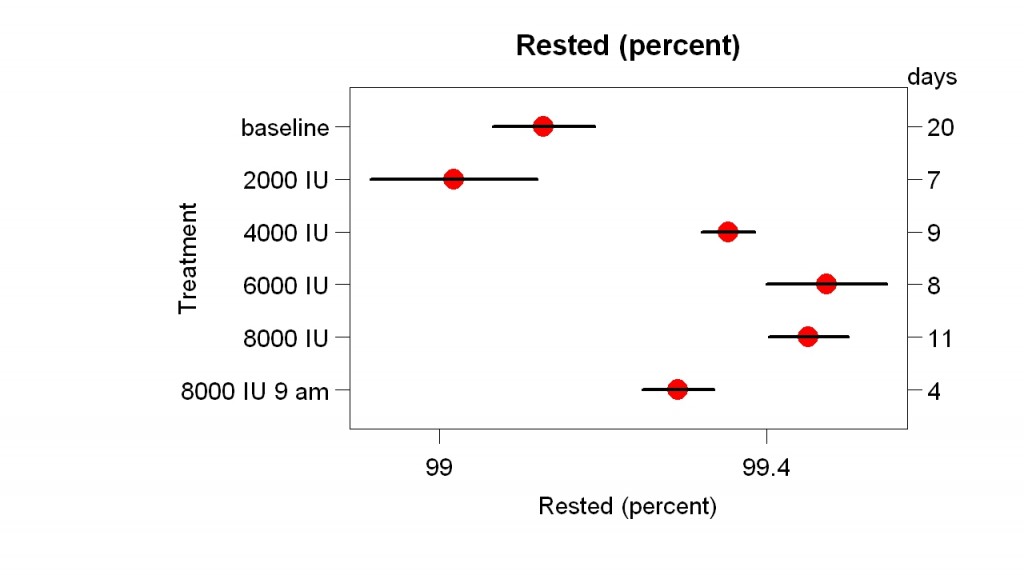

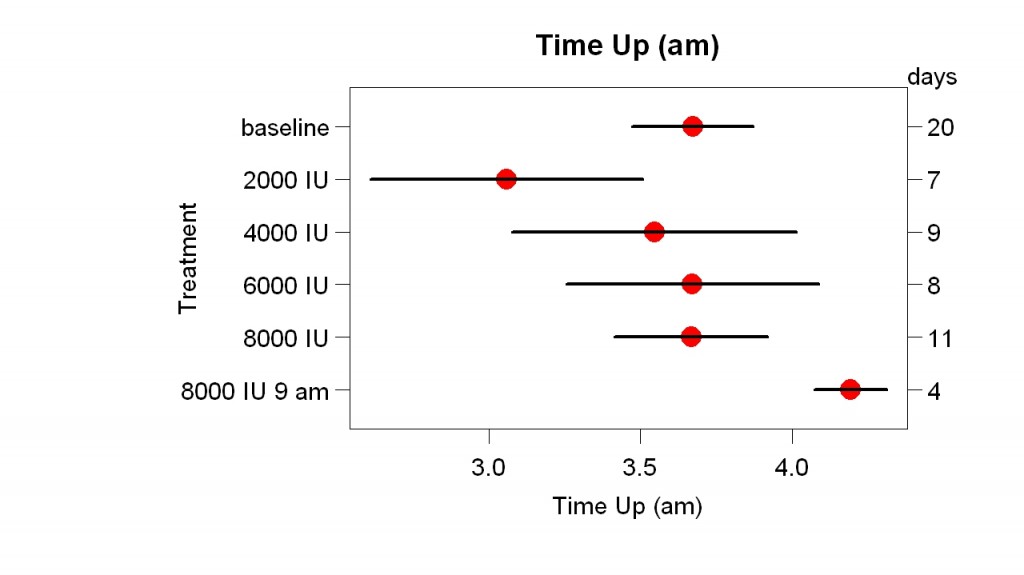

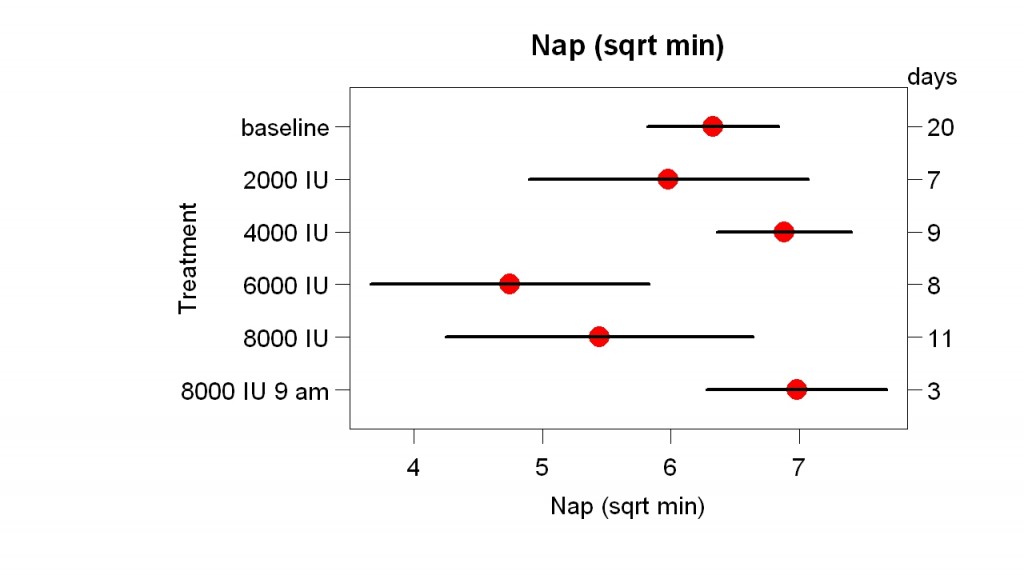

Someday the people in charge of our health care — or the rest of us, ignoring them — will figure out how to make our immune systems work much better. We will sleep much better, eat much more fermented foods, take enough Vitamin D at the right time of day, and so on. Perhaps we will wash our hands less and kiss more. Antibiotic usage will go way down, selection for resistant microbes will become much less intense, and antibiotic-resistant microbes will become much less common. The problem will disappear.