My alternative to Testing Treatments (199 pages), I said recently, is three words: Ask for evidence. Ask your doctor for evidence that their recommendation (drugs, surgery, etc.) is better than other possibilities. A few years ago, I asked Dr. Eileen Consorti, a Berkeley surgeon, for evidence that the surgery she recommended (for a hernia I couldn’t detect) was a good idea. Surgery is dangerous, I said. What about doing nothing?

To reread what I’d written about this (here and here), I googled her. I learned she has a blog. It contains only one post (June 21, 2011). That post is only seven words long. I also learned she has two very similar websites (here and here). Both use her full name and title where most people would use she. Perhaps I caused the blog and websites.

Here’s what happened:

1. In 2008, during a routine physical, my primary-care doctor finds that I have a hernia, so small I hadn’t noticed it. He says I should see Dr. Consorti. Do I need surgery for something so small? I ask. Ask her, he says.

2. Dr. Consorti examines my hernia. She recommends surgery (that she would perform). Why? I ask. It could get worse, she says.

3. Eventually I realize that’s a poor reason. Anything can get worse. Influenced by Robin Hanson, I speak to Dr. Consorti: Surgery is dangerous. What about doing nothing? Is there evidence that the surgery you recommend is beneficial? Dr. Consorti says, yes, there is evidence supporting her recommendation. She says I can find it (studies that compared surgery and no surgery) via Google.

4. I try to find the evidence. I use Google and PubMed. I can’t find it. My mom, who used to be a medical librarian at UC San Francisco, is an expert at this. She has done thousands of medical searches. She too cannot find any studies supporting Dr. Consorti’s recommendation. Moreover, she finds an in-progress study that compares surgery for my problem with doing nothing. Apparently some researchers think doing nothing may be better than surgery.

5. I tell Dr. Consorti that my mom and I couldn’t find the studies she said exist. Dr. Consorti says she will find them. She will let me know when she’s found them and make copies. I can pick them up at her office.

6. Months pass. I call her office twice. No response.

7. In August 2008, I blog about Dr. Consorti’s continuing failure to produce the studies she seemed sure existed.

8. A reader named kirk points out “ what looks like a relevant hernia study“. It concludes: “Watchful waiting is an acceptable option for men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias. Delaying surgical repair until symptoms increase is safe.” This argues against Dr. Consorti’s recommendation. No one points out studies supporting her recommendation.

9. Two weeks after my post, someone who appears to be Dr. Consorti replies. She’s busy. She has 30 new patients with cancer. She terms my question “scientific curiosity”. She says “I will call you once I clear my desk and do my own literature search.”

10. More than a year passes. In 2010, I receive a call from Dr. Consorti’s office. An assistant asks me to remove my blog post about her failure to provide the studies. Why? I ask. It makes her look bad, he says. He says nothing about inaccuracy. I say I would be happy to amend what I wrote to include whatever Dr. Consorti wants to say about it. The assistant asks if I have any “further questions” for her. No, I say. The conversation ends.

11. A little later, I realize I do have a question. In 2008, during the conversation when I asked Dr. Consorti for evidence, I had said surgery is dangerous. In response, she had said no one had died during any of her surgeries. By 2010, I realized that such an answer was seriously incomplete. Many bad things can happen during surgery. Death is only one bad outcome. How likely were other bad outcomes? Dr. Consorti hadn’t said. She knew about these other bad effects much better than I did, yet, in a discussion of the safety of surgery, she hadn’t mentioned them. By not mentioning them, she made surgery sound safer than it actually is. Why had she not mentioned them? That’s my question. I call Dr. Consorti’s office and reach the person who had called me. I ask my question. As I wrote ,

He tried to answer it. I said I wanted to know Dr. Consorti’s answer. Wait a moment, he said. He came back to the phone. He had spoken to “the doctor”, he said. She wasn’t interested in “further dialogue”. She would contact a lawyer, he told me.

I haven’t heard from her since then.

This story illustrates a big change. As recently as twenty years ago, the doctor-patient balance of power was heavily weighted toward the doctor, in the sense that the doctor exerted considerable influence on the patient (e.g., to have surgery). One reason, Robin Hanson has emphasized, is human nature: The more fearful we are, the more we trust. Patients are often fearful. Another reason for the power imbalance was information imbalance. The doctor knew a lot about the problem (had encountered many examples, had read a lot about it). The patient, on the other hand, knew almost nothing and could not easily learn more.

During the last twenty years, of course, this has changed dramatically. Patients can easily learn a great deal about any health problem. Google, PubMed, on-line forums, MedHelp, CureTogether, and so on. The story of Dr. Consorti and me illustrates what a difference the new access to information can make.

Personal science (science done to help yourself) has two sides. One is: collect data. My self-experimentation is an example. To improve my health, I gathered data about myself. It worked. My skin improved, I lost weight, slept better, improved my mood, and so on. The other side is: use data already collected. That’s what I did here. My search for data (including my mom’s search) showed that data already in existence (including the absence of evidence supporting surgery) contradicted Dr. Consorti’s recommendation. My search was not biassed against her recommendation. I didn’t care whether she was right or wrong. I just wanted what was best for me. As Feynman said, science is the opposite of trusting experts — including doctors. My first glimpse of the power of self-experimentation was when it showed me that one of the two medicines my dermatologist had prescribed didn’t work.

Overtreatment is an enormous problem in America. Overtreated by Shannon Brownlee and Overdiagnosed by H. Gilbert Welch, Lisa Schwartzl and Steve Woloshin are recent books about it. Overtreatment could easily be why Americans pay far more for health care than people in any other country yet die earlier than people in many countries. A large fraction of our health care may do more harm than good. A common view is that the incentives are wrong. As one commenter put it, pay for treatment, you get treatment. The solution, according to this view, is to change the incentives. That’s a good idea but will not happen soon. I believe overtreatment can be reduced now. You can (a) ask for evidence (as I did) and (b) search for evidence (as I did). The difference in lifespan between America and other countries suggests this might add years to your life.

I would like to find out what happens when people ask for evidence and/or search for evidence. Please send me your stories or post them in the comments.

More Two days after I posted this, Dr. Consorti replied to this post and the earlier one with essentially the same comment, which is here.

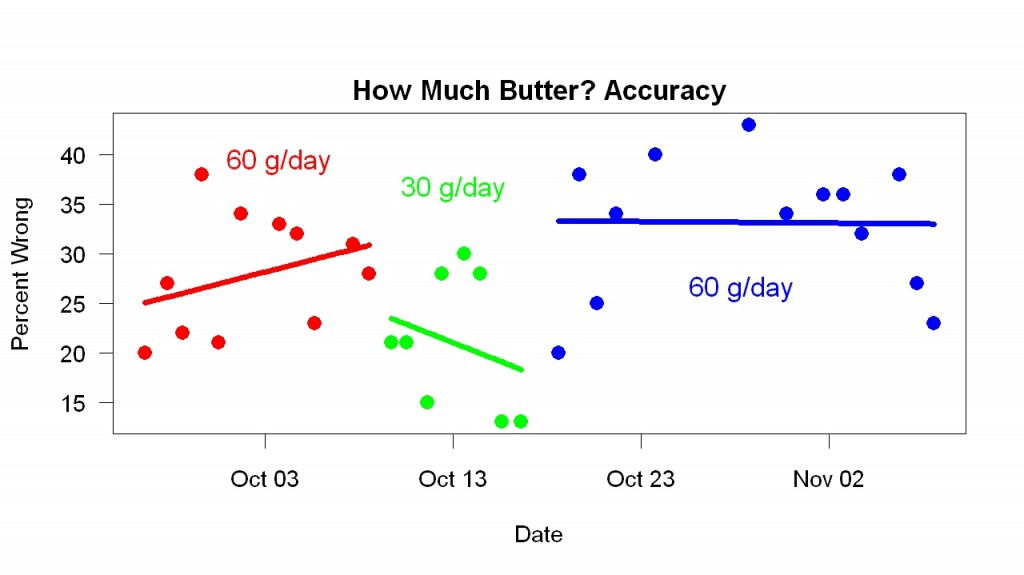

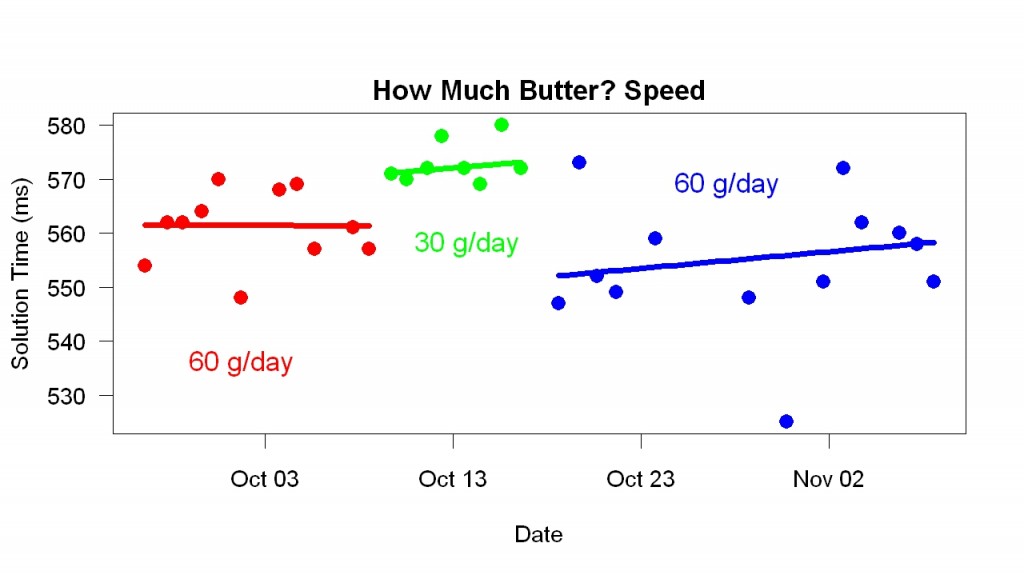

The graph shows that when I switched to 30 g/day, I became slower. When I resumed 60 g/day, I became faster. Comparing the 30 g/day results with the combination of earlier and later 60 g/day results, t = 6, p = 0.000001.

The graph shows that when I switched to 30 g/day, I became slower. When I resumed 60 g/day, I became faster. Comparing the 30 g/day results with the combination of earlier and later 60 g/day results, t = 6, p = 0.000001.