In the comments on yesterday’s post (“Can Vitamin D Replace Sunlight? A Stunning Discovery”), two commenters (John and Aaron Blaisdell) noted that Nephropal had said something similar. They’re right. Here’s what Nephropal said in 2009:

Vitamin D taken at night causes insomnia. This is a complaint of a few of my patients. Moreover, when they switch to morning dosing, the insomnia subsides. Thus, Vitamin D should be taken in the morning.

That’s a great observation, but not the same as Primal Girl’s. Here is her observation, shortened for clarity:

I usually took my supplements mid-afternoon. I vowed to take them first thing every morning. I tried it the next day and that night I slept like a rock. And the next night. And the next.

The two observations support each other. Both support the idea that the timing of Vitamin D matters. But there are also big differences. Paleo Girl had been taking her Vitamin D in mid-afternoon, not at night. She shifted to first thing in the morning, which is more specific than morning. I changed the title of yesterday’s title to make clearer what is new here: the idea that Vitamin D can substitute for sunlight.

Lots of things cause insomnia if you take them in the evening. Caffeine and other stimulants, for example. A comment on yesterday’s post said that B vitamins and calcium cause insomnia if taken in the evening. This is why Nephropal’s observation, although very important, is not a stunning surprise. You stop taking X in the evening, your sleep improves — I won’t be astonished, no matter what X is.

Vitamin D is not a stimulant or is at best a mild stimulant. Taking Vitamin D in the afternoon should not cause trouble sleeping. Yet Primal Girl had trouble sleeping. And she was getting little morning sunlight. It is a real insight that first-thing-in-the-morning Vitamin D could have the same effect as first-thing-in-the-morning sunlight — in other words, could substitute for missing sunlight. Against all odds, the results supported this idea.

One commenter on yesterday’s post said Primal Girl’s results were both unproven and obvious. Vitamin D is technically a hormone! Melatonin is a hormone, said the comment. I have not heard anyone propose taking melatonin first thing in the morning to improve sleep. It is standard to take melatonin in the evening. The accepted view among circadian rhythm researchers is that sunlight produces its effects on circadian rhythms via nerves, not blood. For example, hundreds of experiments have found that destroying the suprachiasmatic nucleus of rats destroys their circadian rhythms. The suprachiasmatic nucleus receives neural input from the eyes — that’s why these lesions were first made (by Irv Zucker, a Berkeley colleague of mine).

Lots of people think Vitamin D improves sleep. That’s not new. Here’s what one of them said, in a post promisingly titled “ When is the best time to take your Vitamin D supplement?“:

In an effort to boost absorption of vitamin D, individuals were asked to take their vitamin D supplements with the largest meal of the day. After 2-3 months, vitamin D levels were checked again.At the end of the study period, vitamin D levels had risen to an average of 47.2 ng/ml (118 nmol/l) – an average i ncrease in vitamin D levels of about 57 per cent. . . It seems sensible, I think, for individuals who are currently supplementing with vitamin D to take this with their largest evening meal.

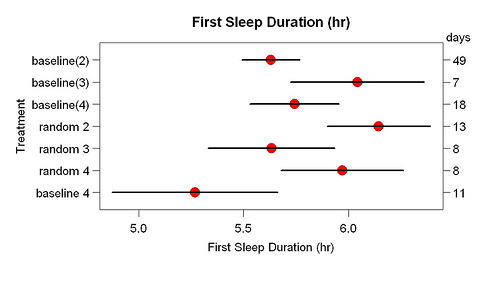

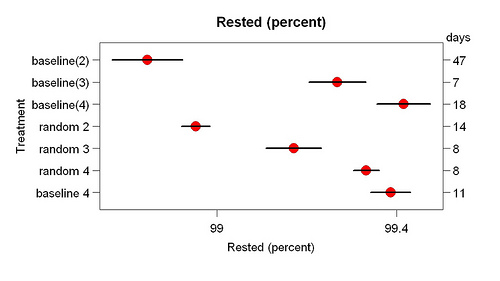

This shows means and standard errors. The number of days in each condition are on the right.

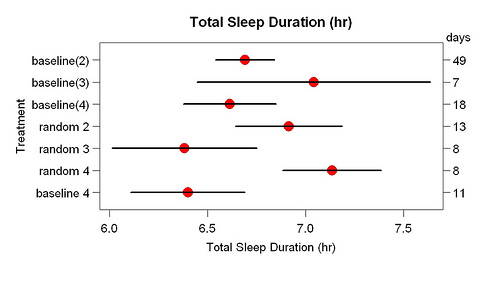

This shows means and standard errors. The number of days in each condition are on the right.