Stuart King writes:

I was very hungry today at dinner and the thought of sweet food wasn’t appealing at all, but after filling up on some rice, chicken and coconut cream curry I immediately had ice cream and chocolate slice [= what Americans call a brownie], which had had no appeal 15 minutes or so before!

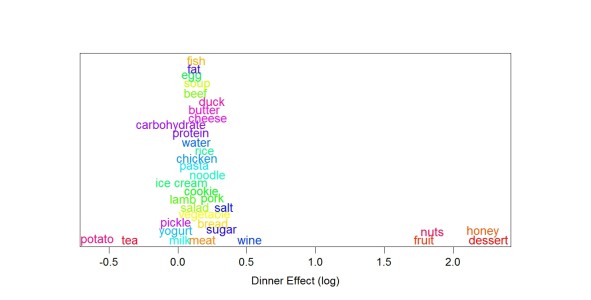

An everyday observation that anyone can make. Studies have shown what Stuart noticed: When you are hungry sweet foods are unappealing. This is why dessert is eaten after the rest of the meal.

The main way that psychologists explain an experimental effect — choose between explanations — is by finding out what makes the effect larger or smaller. For example, discovery of what makes learning more or less (what increases or decreases the effect of one learning trial) is the main way psychologists have chosen among different theories of learning. Different theories predict different interactions.

Why do we like sweet foods? The usual answers are that sweet foods are a “good source of energy” and they provide “quick energy”. But these explanations do nothing to explain what Stuart noticed. If sugar is a good (= better than average) source of energy, we should eat it before other foods (average sources of energy) when we are hungry (hunger signals lack of energy). The opposite is true. You may not want to call it a “contradiction” but there is no doubt the conventional view does not explain what Stuart noticed. Of course many nutrition experts, such as Weston Price, are/were entirely sure sugar is unhealthy.

As a tool for choosing among theories, Stuart’s observation is especially good because (a) it is very large (sweets go from unappealing to appealing) and (b) paradoxical (eating calories should make all calorie sources less appealing).

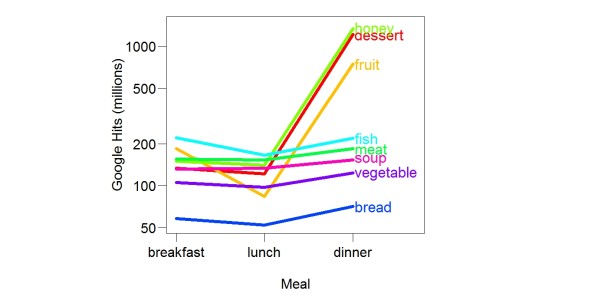

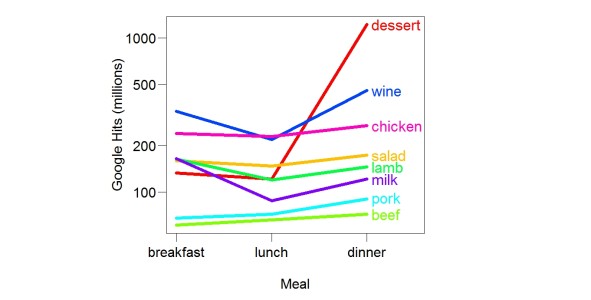

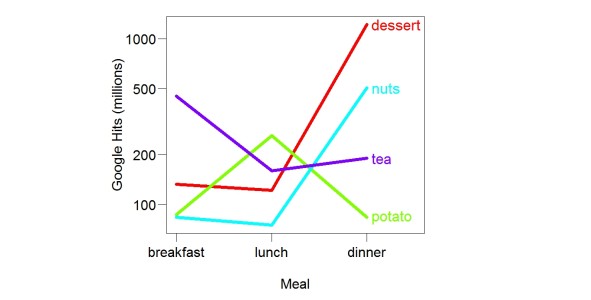

If you have been reading this blog, you know I explain Stuart’s observation by assuming that we need sugar in the evening to sleep well. Sugar (sucrose, fructose, glucose) eaten in the evening increases blood glucose, which increases glycogen. During sleep, glycogen becomes glucose, which the brain needs to work properly. Evolution shaped us to like sweet foods after a meal so that we will eat them closer to when we sleep. (The value of replenishing glycogen close to bedtime also explains why we eat sweet foods after dinner more than after breakfast or lunch.)

I can’t think of another case where what experts say is so out of line with what’s easily observed. For example, I’m sure cholesterol doesn’t cause heart disease, but there is no everyday observation that supports my belief.

I can’t think of another case where what experts say is so out of line with what’s easily observed. For example, I’m sure cholesterol doesn’t cause heart disease, but there is no everyday observation that supports my belief.

If sugar is helpful for sleep, why is it associated with diabetes? My guess is that sugar is almost always consumed in foods that taste exactly the same each time — what in The Shangri-La Diet I called ditto foods. For example, soft drinks. Ditto foods with sugar, because they have a strong precise CS (smell) and a strong fast US (calorie signal), produce an especially strong smell-calorie association. Such an association raises the body fat set point, thus causing obesity. Obesity causes diabetes. It’s also possible that eating sugar during the day — at the wrong time — hurts sleep. Maybe sugar during the day raises insulin and thus reduces the conversion of sugar to glycogen. Less glycogen causes bad sleep, bad sleep causes diabetes. My blood sugar levels clearly improved when I started eating sweets in the evening — opposite to what the sugar-diabetes link would predict.