A friend of mine named Dave saw the BBC program Eat, Fast and Live Longer ten months ago. The program promotes intermittent fasting for better health. It sounded good. Already he often went a day without food. Some Brahmins in South India had eaten this way for millennia – which suggested it made some sense. It wasn’t a fad. Alternate day fasting was simpler than the “fast 2 days per week” regimen the TV show ended with. He started alternate day fasting immediately.

It was easy to start. The first day was hard. He had painful stomach cramps, but hunger was not a problem. The second day of fasting was slightly difficult, again because of stomach cramps. By the third day of fasting, there was no problem. He tried eating a small meal (400-500 calories) on fasting days but it just made him hungry. It was easier to not eat at all.

Within two weeks, his head felt clearer, he had more energy, and he felt lighter. Lots of people say the same thing in YouTube videos about the diet. He had more mental energy. Before the diet, he easily became overwhelmed. In spite of a highly technical background (he was a math professor at an Ivy League school), something as simple as writing a computer program would exhaust him. When he tried to tackle a technical problem, he would get overwhelmed, exhausted, and would quickly give up. For example, he has written tens of thousands of lines of computer code. Writing in a language he knew very well, he’d be unable to get beyond 10-15 lines. Within three months of starting the diet, he took an online class (an introductory class about R) and was surprised he could do the work. (He had started the class to take his mind off of family issues he had to deal with. He wanted to do something for himself.) After that, he took two more online classes, about cryptography and about functional programming. He finished them and did well. He was elated.

Several other things started improving. He’d had GERD (“acid reflux”). He had poor digestion at night, would wake up with an “acidic stomach” and burning in the back of his throat and mouth. He’d had this all his life (he’s now in his fifties). In his twenties, several health experts told him he had digestive problems. When he started alternate day fasting, he didn’t change the time of day that he ate. After two or three months, his GERD entirely went away.

Another improvement was athlete’s foot. He’d had it since his mid-twenties. He had it all over his feet, not just the toes. He’d done many things to get rid of it. None of them worked, at least permanently. After two months of alternate day fasting, he noticed improvement. Over the following months his athlete’s foot continued to improve. However, three weeks ago he started drinking a half-gallon of yogurt per week. Within two weeks of starting that, his athlete’s foot got much worse. Eating much more yogurt was the only dietary change he’d made. The connection (yogurt increased athlete’s foot) is plausible because athlete’s foot is due to one or more fungi, fungi need sulfur to grow, and yogurt contains a lot of cysteine, which contains sulfur. (A natural therapy site gets it exactly wrong: “Continuing to consume yogurt . . . on a daily basis after the immediate problem has been solved may prevent future outbreaks”).

His food allergies started going away. Wheat was the worst. After eating wheat, he got brain fog, agitation (difficulty sitting still), and difficulty focusing. He would start having violent imagery; for example, his dreams will get quite violent. A laboratory test showed that he had astronomical levels of an immune response to gluten peptides. Another food allergy of his was dairy. It caused agitation, difficulty concentrating, and depression (in the sense that you feel like you want to kill yourself). Before he figured this out, there were times he consumed a quart of milk in a short period of time. Half an hour later, he got these three symptoms, including scary depression (“there’s no way out”). Now he can consume both wheat and dairy without trouble. His wheat allergy isn’t entirely gone but it is much better. He hasn’t noticed any allergic reaction to dairy, even large amounts.

He’d had blood sugar problems for a long time. He’d had hypoglycemia since his late twenties. After strenuous exercise, he could come close to passing out. He would eat fruit to keep this from happening. He’d be lying on the floor, drag himself to eat a piece of fruit, and instantly feel better. After a meal, he’d feel tired, then eat something sweet and feel a rush of energy. He had a regular need for sweet things, including dessert. Whenever he had dinner, he’d really want dessert. About eight months after he started alternate day fasting, he realized that his craving for something sweet went away. One day it was present, the next day gone. Instead of feeling tired after a big meal, he felt calm.

He thinks that he must have had a candida infection and his gut is healing. This would explain the allergies going away and the GERD improvement. He hadn’t expected these changes. He just started it because it fit his eating patterns and was more regular.

“I’ve experienced hunger for the first time,” he says. If he doesn’t eat the morning of a day he’s supposed to eat, he feels ravenously hungry – a new experience. A crystal-clear sense of hunger, which is pleasant. It’s pleasant to know what hunger is. He takes meals more seriously, because that’s the day he’s eating. He pays more attention to his food.

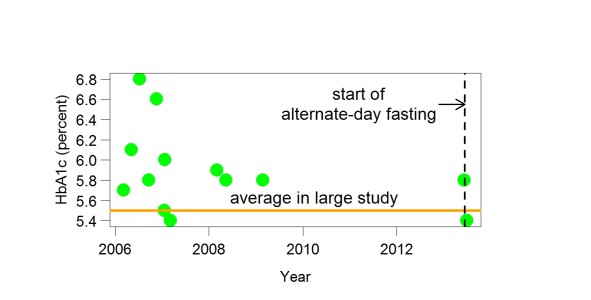

I found his experience far more convincing than anything else I’d heard about intermittent fasting. It was sustainable, it was easy, the benefits were unexpected, no ideology was involved, all sorts of things got better. It was as if this was the eating pattern our bodies were built for. My friend’s experience led me to try alternate day fasting, as I’ve said. After a few days my fasting blood sugar substantially improved (from the mid-90s to the mid-80s). Within weeks, my HbA1c went from 5.8 to 5.4. I haven’t noticed mental changes but my brain test scores have improved for reasons I cannot yet explain (there are several possible explanations).