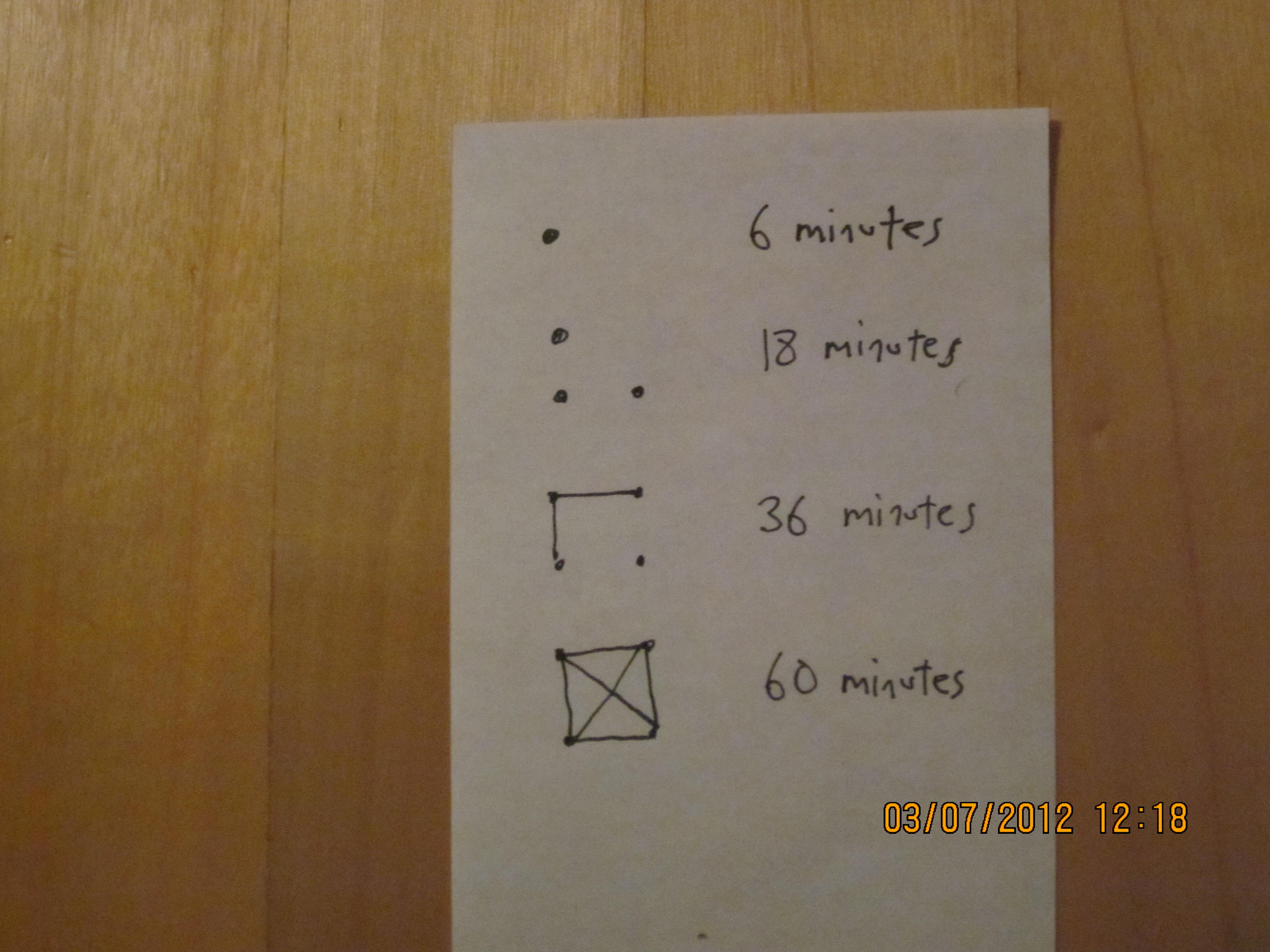

One of my recent posts about anti-procrastination software led a reader named Joan to an earlier post about magic dots, which is a low-tech way of getting work done. Every six minutes of work, you make a dot or line in a certain pattern on a piece of paper. I got the idea from the quasi-reinforcement effect of Neuringer and Chung. Studying pigeons, they found that markers of progress act like rewards. What was amazing was that they got pigeons to work twice as hard (= peck twice as fast) without increasing their salary (= food reward). The dots mark progress.

In her comment, Joan said

This post led me to find the post about the magic dots, which for me [have been] magic. I have a fairly boring job and lots of annoying things I have to take care of for my family, so it’s hard to get going most days. Today I got going right away and stayed on task. I didn’t use a stop-watch, just wrote down the time I started, and created the boxes. I started this yesterday afternoon, so this is one and a half days.

I asked her for details. She replied:

I have an IT job where I am pretty much self-directed, but one week out of four have to be on-call for production support, which takes up most of the time that week, and I also have to assist the on-call person the other 3 weeks when it’s an application I own. Since I spend the on-call week pretty much just monitoring 3 mailboxes, it’s very hard to focus on the off weeks, and I find myself reading blogs way too much of the time. Also, some of the production support work is interesting -figuring out what happened and how to fix it, but a lot of it is routine and annoying, like some external server was down, so we have to rerun a job.

I have tried various tools to block the most addictive sites, but am not really supposed to install stuff on my work computer. The percentage thing looked interesting, but it looked like it would be minor project to implement. Then I saw the post about magic dots. I’m a “tactile” learner, which means I like to write stuff on paper, so I thought this would be easy to try and started right away. I was already trying to keep a list and give myself checkmark rewards, without much success.

So far this week has been great — I follow this very loosely. I make a list of activities to accomplish between production support calls, including stretching, etc. and anything that is not something to be done immediately. So things that might not be “work”, but that I have to get done that day during the day are on the list, and I fill in between support work with this stuff. I count time spent chatting with co-workers, calls to my mother, calls to the bank, even this email.

The first 2 days were pretty hard. I found myself scanning the list for the least annoying or tiresome tasks, but toward the end of the day I was actually pushing myself to stay and finish a couple of issues that would fit in my time remaining, and empty those in-boxes.

I’m not that focused on filling in the dots [= completing a set of 10] as the day goes on, but after every break I start a new one, and note the time I started.

I have no idea why this works, when nothing else seems to have helped.

I asked what else she had tried. She replied:

I had some success with LeechBlock, but had to remove unauthorized apps [LeechBlock is a Firefox addon] from my desktop and [had to stop] using it to stay off the really addictive sites such as ancestry.com. Work already blocks most social media sites. I tried using the IE site blocking, but having to enter a password didn’t seem to deter me.

To try to get motivated and get more done I have:

- Affirmations and resolutions. Fail.

- Tried using a “7 habits” style to do list. Fail.

- Putting little mirrors on my desk. No help.

- Improve another habit and hope for carryover. I tried food monitoring, and spent too much time researching diets. I am keeping up with exercise goals though.

- Looked for support or monitoring sites. Did not find one that seemed like a good fit. Internet addiction forums are mostly about porn or gaming addictions, not ancestry.com or paleo diet blogs.

- I followed a popular “personal productivity” blog for a while, but in the end spent too much time reading the forums. Seems like most of these gurus have always been over-achievers.

Based on statistics I have heard, I’m only a little above average in internet use at work, but some days I’m way over.

![IMG_0245[1]](https://sethroberts.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/IMG_02451-300x225.jpg)