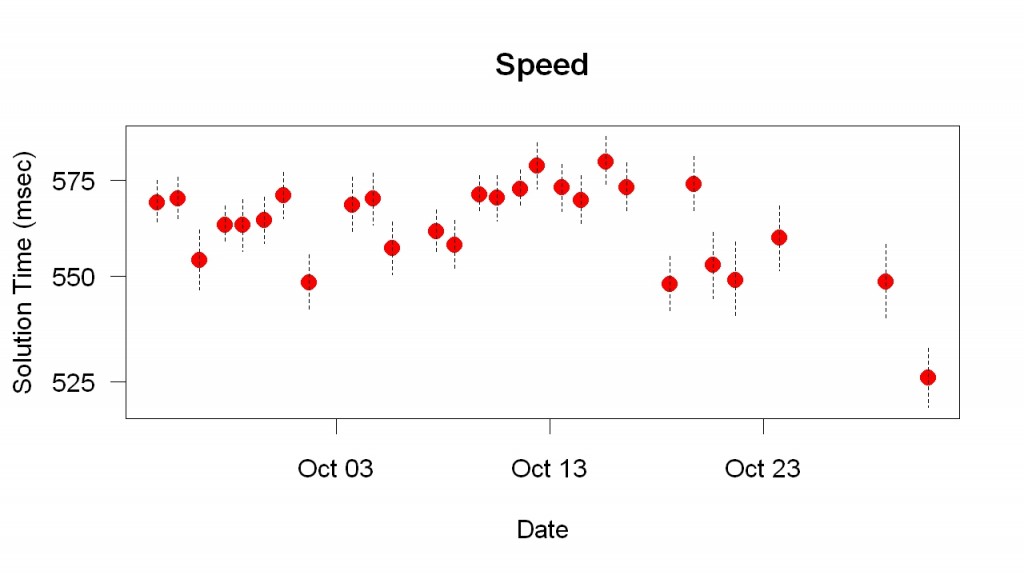

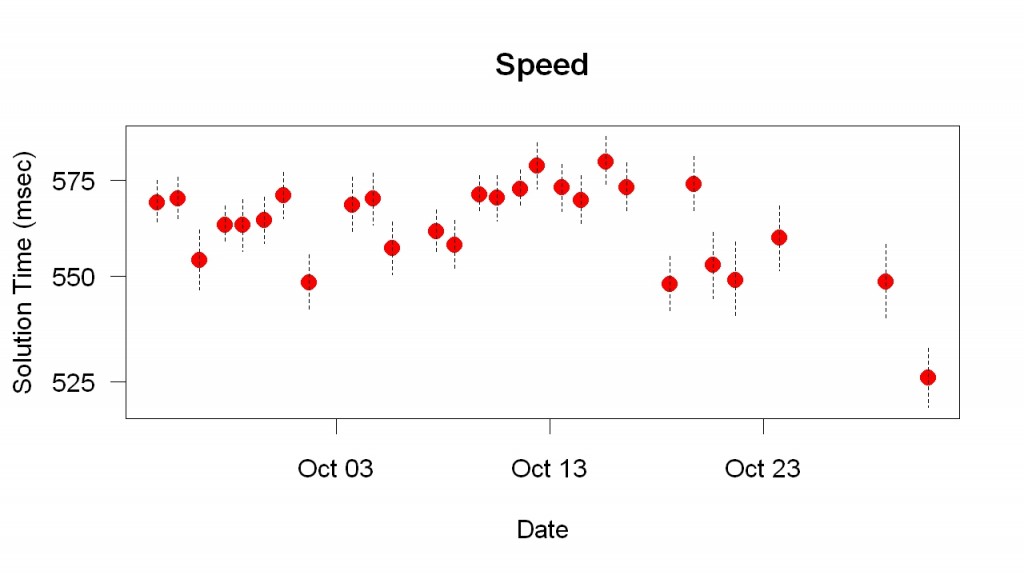

For the last four years or so I have daily measured how well my brain is working by means of balance measurements and mental tests. For three years I have used a test of simple arithmetic (e.g, 7 * 8, 2 + 5). I try to answer as fast as possible. I take faster answers to indicate a better-functioning brain.

Yesterday my score was much better than usual. This shows what happened.

My usual average is about 550 msec or more; my score yesterday was 525 msec. An unexplained improvement of 25 msec.

What caused the improvement? I came up with a list of ways that yesterday was much different than usual, that is, was an outlier in other ways. These are possible causes. From more to less plausible:

1. I had 33 g extra flaxseed last night. (By mistake. I’m not sure about this.)

2. The test came at the perfect time after I had my afternoon yogurt with 33 g flaxseed. When I took flaxseed oil (now I eat ground flaxseed), it was clear that there was a short-term improvement for a few hours.

3. Many afternoons I eat 33 g ground flaxseed with yogurt. Yesterday I ground the afternoon flaxseed an unusually long time, making made the omega-3 more digestible.

4. I did kettlebells swings and a kettlebell walk about 2 hours before the test. These exercises are not new but usually I do them on different days. Yesterday was the first time I’ve done them on the same day. I’m sure ordinary walking improves performance for perhaps 30 minutes after I stop walking.

5. I had duck and miso soup a half-hour before the test. Almost never eat this.

6. I had a fermented egg (“thousand-year-old egg”) at noon. I rarely eat them.

7. I had peanuts with my yogurt and ground flaxseed. Peanuts alone seem to have no effect. Perhaps something in the peanuts improves digestion of the omega-3 in the flaxseed.

8. I started watching faces at 7 am that morning instead of 6:30 am or earlier.

Here are eight ideas to test. Perhaps one or two will turn out to be important. Perhaps none will.

After I made this list, I read student papers. The assignment was to comment on a research article. One of the articles was about the effect of holding a warm versus cold coffee cup. Holding a warm coffee cup makes you act “warmer,” said the article. Commenting on this, a student said she thought it was ridiculous until she remembered going to the barber. She sees the person who washes her hair (in warm water) as friendly, the barber as cold. Maybe this is due to the warm water used to wash her hair, she noted. This made me realize another unusual feature of yesterday: I had washed my hair in warm water longer than usual. I think I did it at least 30 minutes before the arithmetic test but I’m not sure. In any case, here is another idea to test. I found earlier that cold showers slowed down my arithmetic speed.

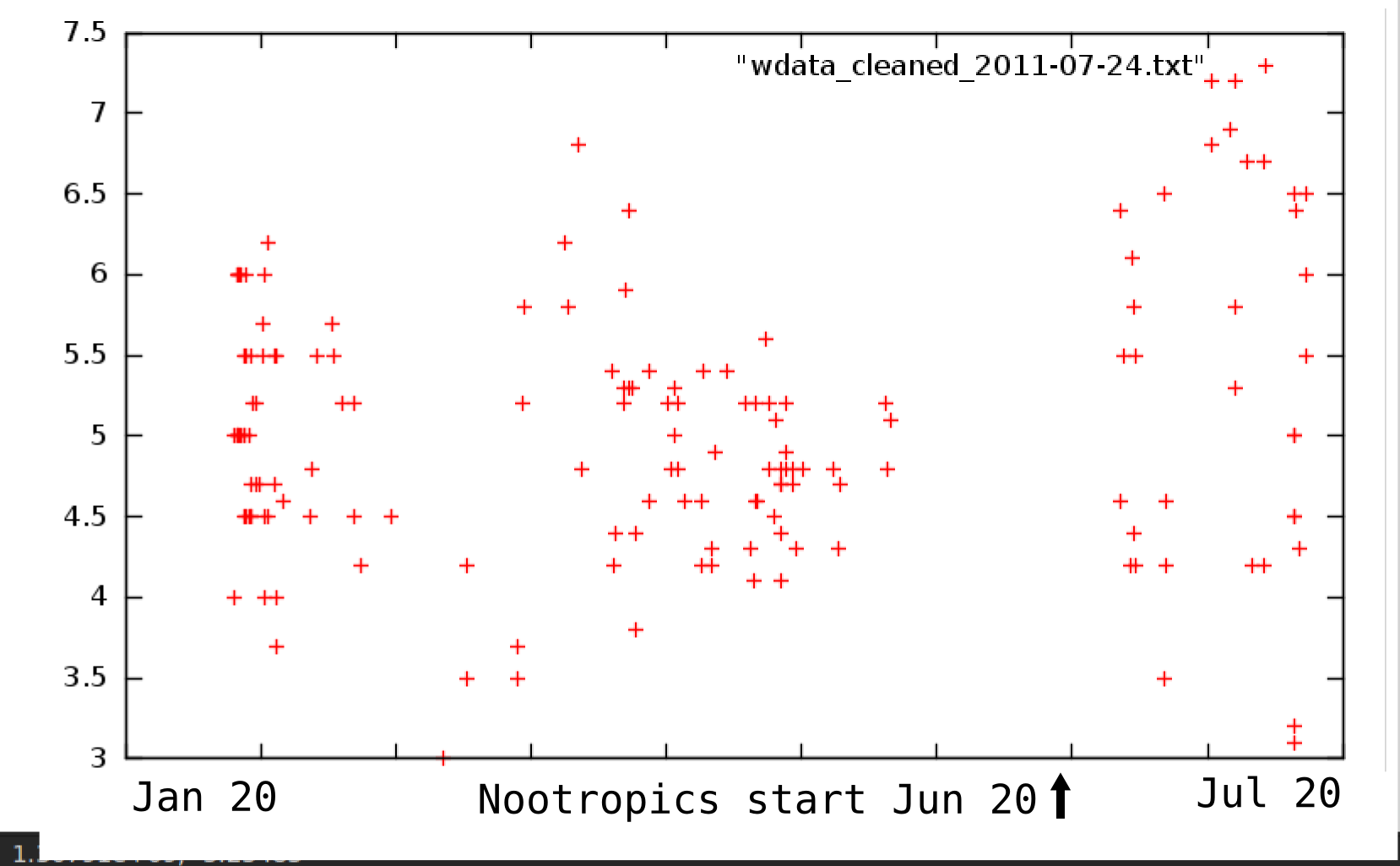

This illustrates a big advantage of personal science (science done for personal gain) over professional science (science done because it’s your job): The random variation in my life may suggest plausible new ideas. As far as I can tell, professional scientists have learned almost nothing about practical ways to make your brain work better. You can find many lists of “brain food” on the internet. Inevitably the evidence is weak. I’d be surprised if any of them helped more than a tiny amount (in my test, a few msec). The real brain foods, in my experience, are butter and omega-3. Perhaps my tests will merely confirm the value of omega-3 (Explanations 1-3). But perhaps not (Explanations 4-8 and head heating).