This recent study from Japan found that middle-aged men and women who ate more saturated fat had a lower risk of stroke. The rate of strokes was 30% lower in the highest intake quintile compared to the lowest quintile. There was a non-significant reduction in heart disease.

Other big differences were correlated with saturated fat intake. For example, those in the highest quintile had more college education than those in the lowest quintile and were more likely to do sports >1 hr/week. These data by themselves won’t convince anyone that saturated fats are beneficial. But they should push you in that direction. Contrary to what you’ve heard a million times.

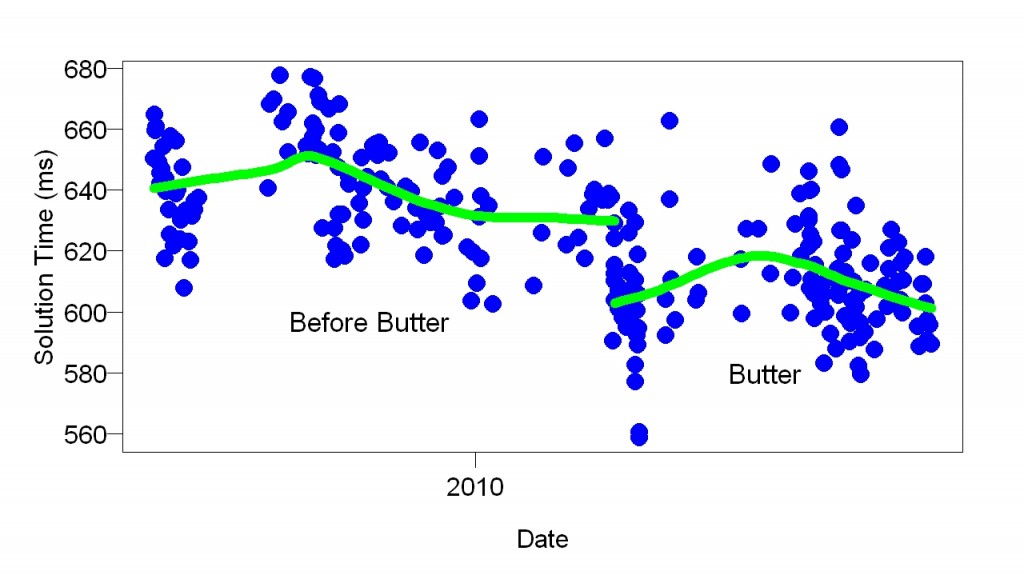

As far as I can tell, eating lots of butter has lowered my blood pressure. High blood pressure is associated with greater risk of stroke.

Although pig fat certainly helped me (I slept better), I’ve found butter is even better. Butter has considerably more saturated fat than pig fat. The fat in butter is 60% saturated fat, whereas pig fat is 40% saturated fat. My consumption of 60 g/day of butter gives me 36 g/day saturated fat. In this study, persons in the highest quintile of intake averaged 20 g/day. The highest intake in the whole study (60,000 people) was 40 g/day. In addition to butter, I eat cheese, whole-fat yogurt, and meat, so I’m surely higher than that.

Via Whole Health Source.