Uffe Ravnskov, a Swedish doctor, wrote a paper titled “Is atherosclerosis caused by high cholesterol?” (An admirably clear title.) His answer was no. He submitted it to a medical journal. One of his empirical points was that there was no relationship between cholesterol level and atherosclerosis growth. One reviewer commented:

Lack of relationship can be explained by more factors that only absence of it: small numbers, incorrect or indirect measurements of variables of interest, imprecision in measurement, confounding factors, etc.

To which Ravnskov replied:

If it is impossible to find exposure-response between changes of blood cholesterol and atherosclerosis growth in 22 studies including almost 2500 individuals a relationship between the two, if any, must be trivial.

Which sounds reasonable. But an even larger number of clinical trials failed to find clear evidence that omega-3 supplementation reduces heart disease. Yet I am sure that, with a large enough dose, it does.

Most people believe clinical trials, which are usually double-blind when possible and placebo-controlled. “The gold standard,” they are called. Science writer Gary Taubes, for example, believes them: When the results of a clinical trial contradicted a survey result, he believed the clinical trial. His recent NY Times magazine article was based on the assumption that clinical trials are trustworthy. This is such an article of faith that he gave no evidence for it.

That the heart disease clinical trials failed to clearly show benefits of omega-3 supplementation had large and unfortunate consequences. Not only because heart disease is the leading cause of death in many places, including America, but also because I am sure proper omega-3 supplementation would reduce many other problems, including falls, memory loss, gum disease, and other diseases of too much inflammation.

I don’t know why the big clinical trials failed to point clearly in the right direction. I can think of several possibilities:

1. Too large. Hard to control quality — verify data, for example. People near the bottom doing the work have little stake in accuracy of the outcome.

2. Poor compliance. If you are taking the placebo, why bother? And the odds are fifty-fifty you are. Lots of people have trouble following SLD, which obviously works.

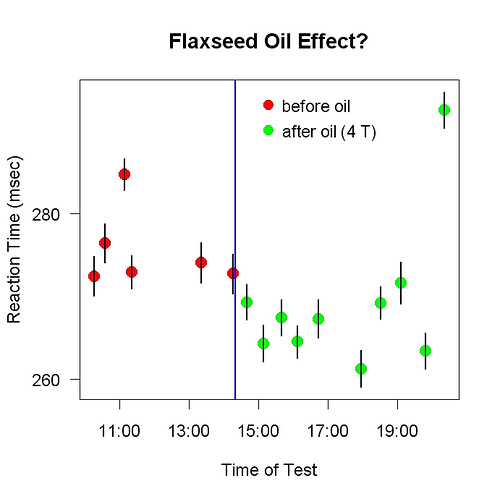

3. Degradation. My belief that omega-3 is powerful comes from experiments (mine) and examples involving flaxseed oil. Flax grows at room temperature. The heart disease studies used fish oil; fish live in cold water. The omega-3 fats in fish oil may degrade at room temperature. The omega-3 fat in flaxseed oil may be far more stable at room temperature.

4. Wrong dose. Self-experimentation made it easy for me to figure out the correct dosage. People studying heart disease had no similar data to guide them. They could not realistically expect people to consume as much fish oil as the Eskimos whose rate of heart disease was so low.

5. Too sure. Self-experimentation encourages skepticism about one’s results because new experiments are easy to do. If I can think of reasons to doubt my results so far, that’s a good excuse for a new experiment. The more experiments the better. Each one is easy; I just need a good story line, a good reason for each one. Whereas if you are doing an experiment that cannot be repeated, any skepticism about it — e.g., about accuracy of measurements — is discouraged: It would cast doubt on the whole enterprise.