Susan Allport is the author of The Queen of Fats: Why Omega-3s Were Removed from the Western Diet and What We Can Do to Replace Them, which for me was the best source of introductory information on the subject. Chapter 1 is here. A video.

What have been the main reactions to your book?

The best reaction has been from scientists and the American Oil Chemists Society (AOCS), whose members were happy to have the history of this important research laid out for the public and for themselves. The book hasn’t yet caught on with general readers — in part because the material is somewhat difficult and in part because most people think that the problems with fats are with trans fats or saturated fats or cholesterol: three long detours on the road to dietary understanding, in my opinion.

Learned anything since you wrote it that you would include in a revised/expanded edition?

I would certainly include a key piece of evidence that has been available for some time but not brought to light. It has to do with the argument that we don’t elongate and desaturate the parent essential fatty acids very well (the omega-3 fat: alpha linolenic acid and omega-6 fat: linoleic acid). Therefore, the argument goes, it doesn’t matter about the quantities of these parent fats in the diet. What matters is the amount of long chain fats (in fish, etc.)

But here’s the rub and the lie to this argument.

According to the Nationwide Food Consumption Survey and other data, Americans consume more long chain omega-3 fatty acids than they do long chain omega-6 fatty acids (See “Polyunsaturated fatty acids in the food chain in the US”, Am J Clin Nutr 2000;71 S 179s-88s.) Yet their tissues are full of these highly inflammatory omega-6 fats.

How did this happen? There is only one way. The large amount of linoleic acid in the diet (about 7% of energy) overwhelms and outcompetes the much smaller amount of alpha linolenic acid (about .7% of energy). So it does matter how much linoleic acid we consume. Linoleic acid is the elephant in the living room and the reason we are experiencing the many chronic illnesses that are associated with an insufficiency of omega-3s.

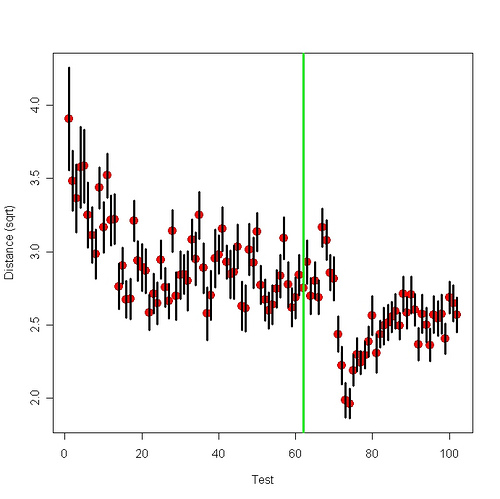

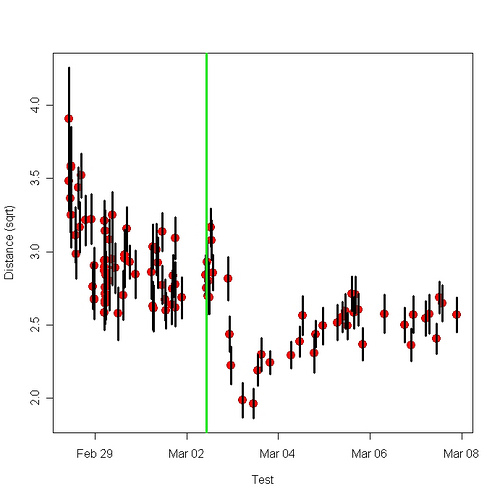

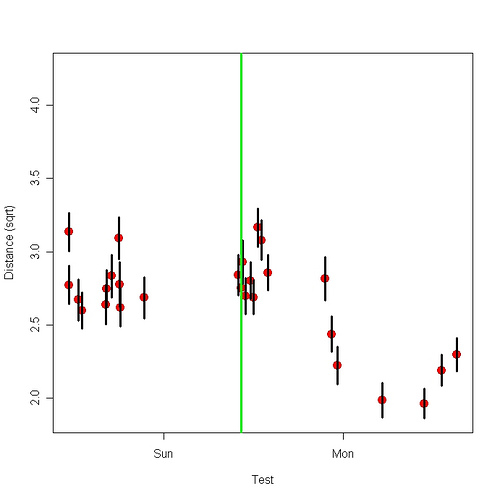

I like to think that anyone who has read my flaxseed oil results (flaxseed is high in alpha linolenic acid, the short-chain omega-3 fat) would agree. Next question: My impression is that the optimal amount of omega-3 is highly unclear. Do you agree?

The optimal amount of omega-3s in one’s tissues does seem to vary, somewhat, according to where one lives. In the cold Artic, humans benefited from a very high proportion of omega-3s in their tissues, and there they weren’t penalized for having a lower proportion of omega-6s b/c there are few infectious microorganisms in the Artic. (Omega-6s, remember, are important in mounting a good immune response.) In more temperate and tropical regions, we need a more balanced amount of 3s and 6s in our tissues. We’ll be learning a lot more about these optimal amounts in the future.

What’s most critical to understand, though, is that omega-3s and omega-6s compete for enzymes and for positions in our cell membranes. So the amount of omega-3s you need to eat in order to achieve a given (optimal) amount in your tissues depends entirely on the amount of omega-6s you’re eating. If you’re eating small amounts of omega-6s, you need to eat only small amounts of fish and greens. If you’re eating, as most Americans are, large amount of omega-6s, you’ll need to eat large amounts of fish and greens — more fish than there are in the ocean!

Which widely-listened-to nutrition expert or group of experts has best appreciated the importance of omega-3s? Which has worst appreciated them?

I’ve had very good conversations with Dr. Mehmet Oz, and I know that Andrew Weil has a very good understanding of the issues. Epidemiologists seem to have the least appreciation because they have little knowledge and appreciation of biochemistry, in general.

In that last question I was thinking of Walter Willett, whose book Eat Drink and Be Healthy fails to clearly distinguish omega-3 and omega-6 fats. Since he’s an epidemiologist, that agrees with what you say. Can you say more about the reaction of epidemiologists?

For Willett to observe the difference between the two families of fats in his type of research, he would need subjects with very different proportions of these fats in their tissues. He doesn’t have that since all of his subjects eat a similar American diet. He also doesn’t see it because he doesn’t control for the two families and their competitive interactions. What we need to do to achieve a good understanding of the role of the two families of essential fats in health and disease is to take experimental work (which clearly shows important differences b/n the two families) and use it to frame our prospective studies. (And because of the competitive interactions, we can’t use fish intake as an indication of omega-3 status; we must use tissue levels of the two families!)