- n=1 tests of low-carb products. Are low-carb versions of everyday foods (such as pasta) better for your blood sugar, as claimed?

- Chelation improves Alzheimer’s. After lengthy trial and error.

- How to teach computer programming. The article contains a quote (“That student is taught the best who is told the least”) from Robert Moore, a college mathematics teacher. An article by Paul Halmos about Moore’s method (“The best way to learn is to do” it began) inspired me to start my self-experimentation.

- Overview of the first Quantified Self conference

Category: personal science

Conway’s Law and Science

Conway’s Law is the observation that the structure of a product will reflect the structure of the organization that designed it. If the organization has three parts, so will the product. In the original paper (1968), Conway put it like this:

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.

Here is an example:

A contract research organization had eight people who were to produce a COBOL and an ALGOL compiler. After some initial estimates of difficulty and time, five people were assigned to the COBOL job and three to the ALGOL job. The resulting COBOL compiler ran in five phases, the ALG0L compiler ran in three.

A consumer — someone outside the organization who uses the product — wants the best design. Conway’s Law implies they are unlikely to get it.

I generalize Conway’s Law like this: It is hard for people with jobs to innovate — for reasons that outsiders know nothing about. Whereas persons without jobs have total freedom. An example is a politician who promises change but fails to deliver. The promises of change are plausible to outsiders (voters) so they elect the politician. However, being outsiders, they barely understand how government works. When the promised changes don’t happen, the voters are “disillusioned”.

To me, the most interesting application of the generalized law is to science. In my experience, people who complain about “bad science”, such as John Ioannides and Ben Goldacre, have the same incomplete view of the world as the “disillusioned” voters. They fail to grasp the constraints involved. They fail to consider that the science they are criticizing may be the best those professional scientists can produce, given the system within which they work. Better critiques would look at the constraints the professional scientists are under, the reasons for those constraints, and how those constraints might be overcome.

“Much research is conducted for reasons other than the pursuit of truth,” writes Ioannidis. Well, yes — people with jobs want to keep them and get promoted. They want to appear high status. That’s not going to change. It’s absolutely true that drug company scientists slant the evidence to favor their company’s drug, as Irving Kirsch explains in The Emperor’s New Drugs. But if you don’t understand what causes depression and you’re trying to produce a new anti-depressant and you want to keep your job . . . things get difficult. The core problem is lack of understanding. Lack of understanding makes innovation difficult. Completely failing to understand this, Ioannidis recommends something that would discourage new ideas: “We must routinely demand robust and extensive external validation—in the form of additional studies—for any report that claims to have found something new.”

Truly “bad science” has little to do with what Ioannides or Goldacre or any quackbuster talks about. Truly bad science is derivative science, science that fails to find new answers to major questions, such as the cause of obesity. Failure of innovation isn’t shown by any one study. Given the rarity of innovation, it is unwise to expect much of any one study. To see lack of innovation clearly you need to look at the whole distribution of innovation. Whether the system is working well or poorly, I think the distribution of innovation resembles a power law: most studies produce little progress, a tiny number produce large progress. The slope of the distribution is what matters. Bad science = steep downward slope. With bad science, even the most fruitful studies produce only small amounts of innovation.

Just as outsiders expect too much from professionals, they fail to grasp the innovative power of non-professionals. Mendel was not a professional scientist. Darwin was not a professional scientist. Einstein did his best work while a patent clerk. John Snow, the first person to use data (a graph) to learn the cause of an infection, was a doctor. His job had nothing to do with preventing infection. To improve innovation about health (or anything else), we should give more power to non-professionals, as I argued in my talk at the First Quantified Self Conference.

Thanks to Robin Barooah.

Assorted Links

- How one obscure sentence upset the New York Times by Renata Adler. A great and revealing story. My explanation of the Times’ s over-the-top hostility to Adler’s book (Gone: The Last Days of The New Yorker) differs from Adler’s. She says it was due to her lack of deference, whereas I suspect currying favor with Charles McGrath, the editor of the New York Times Book Review, was a big part of it. In Gone, Adler criticized McGrath, who was apparently very upset. Gone is the rare critique that combines negativity and deep familiarity. Usually you have one or the other.

- fish oil and joint pain

- life and death consequences of job choices

- one more reason for health care stagnation. Innovations excluded by hospital purchasing groups.

- pickled vegetables and cancer. Alas.

- On the other hand, yogurt linked with lower risk of colon cancer. This study points in the same direction.

Thanks to Dave Lull and Alex Chernavsky.

Assorted Links

- personal genetics

- The man cured of AIDS. The researcher responsible is an insider/outsider — not an AIDS researcher. Robert Gallo, whom I wrote about long ago, is dismissive.

- Drug companies behaving badly. “Prosecutors charged that Forest [a drug company] deliberately ignored an FDA warning to stop distributing an unapproved thyroid drug, promoted the use of an antidepressant in treating children although it was only approved for adults and misled FDA inspectors making a quality check at a manufacturing plant.”

- The iPad foretold (1988).

Thanks to Michael Bowerman.

Highlights of the First Quantified Self Conference

The First Quantified Self Conference happened last weekend in Mountain View. It resembled a super-duper QS meetup: more talks, more varieties of expression (short talks, long talks, booths, posters, breakout sessions, panels), people from far-flung places, such as Switzerland, and more friends.

Above all, it felt sunny, after a long overcast. Something I’d done most of my life was now enthusiastically being done by many others. Other highlights for me:

Talking with Steve Omohundro, an old friend I hadn’t seen in years. After I saw him on the attendee list, I aimed it at him. After it, he came up and said he really liked it. Mission accomplished ![]() . Like so many smart people, he has started to eat paleo.

. Like so many smart people, he has started to eat paleo.

Meeting John de Souza. I really admire what he has done at Medhelp (“the world’s largest health community”). I like to think that, in the future, the first thing you’ll do when you have a serious health problem will be to contact others who’ve had that problem.

Christine Peterson‘s poster. She measured her sleep with a Zeo for three months. Her poster showed how various things, such as caffeine consumption, correlated with sleep measurements, such as REM time. I believe the most important Zeo measurement is how long you are awake during the night (less is better). Christine’s data showed a strong correlation between her score on Zeo’s Sleep Stealer‘s index (you get points for all sorts of things, such as alcohol consumption, that studies have shown disrupt sleep) and how long she was awake at night. With a high score, she was awake twice as long (about 1.5 hours) as with a low score. This shows the practical value of the Zeo. Assuming that the correlation reflects cause and effect, it’s now clear how she can improve her sleep (reduce her Sleep Stealer score). It also shows that what’s true for other people is true — in the sense of helpful – for her.

The difference between two breakout sessions. Robin Barooah and I ran two breakout sessions about self-experimentation. In the first (many attendees), we talked about 15% of the time. In the second (six attendees), we talked about 5% of the time. In the second, but not the first, it became clear that everyone had something they wanted to talk about. If they could talk about it, they were pleased.

Migraines. I met a woman who used self-experimentation to figure out that her migraine headaches were due to common household chemicals. Doctors had repeatedly told her she had a brain tumor. One doctor had proposed trying twenty-odd medicines one by one until one of them worked.

Speaking advice. Melanie Cornwell, a friend of Gary Wolf’s, gave me advice about my talk. I’m sure her advice will help me in the future.

Mood improvement via sharing. At an excellent mood measurement breakout session run by Margie Morris, I learned how Jon Cousins had tracked his mood for several years and then started to share it with a friend. The sharing had a huge positive effect. He has started a website called Moodscope to help others do this. At the same session Alexandra Carmichael told about sharing mood ratings with someone who, at first, was not an especially good friend but who became her best friend. The sharing improved her mood ratings and curiously their moods become more synchronized.

So I enjoyed the conference on several levels: socially, professionally, and intellectually. Above all, as I said, it was a relief to finally meet others with similar values and goals.

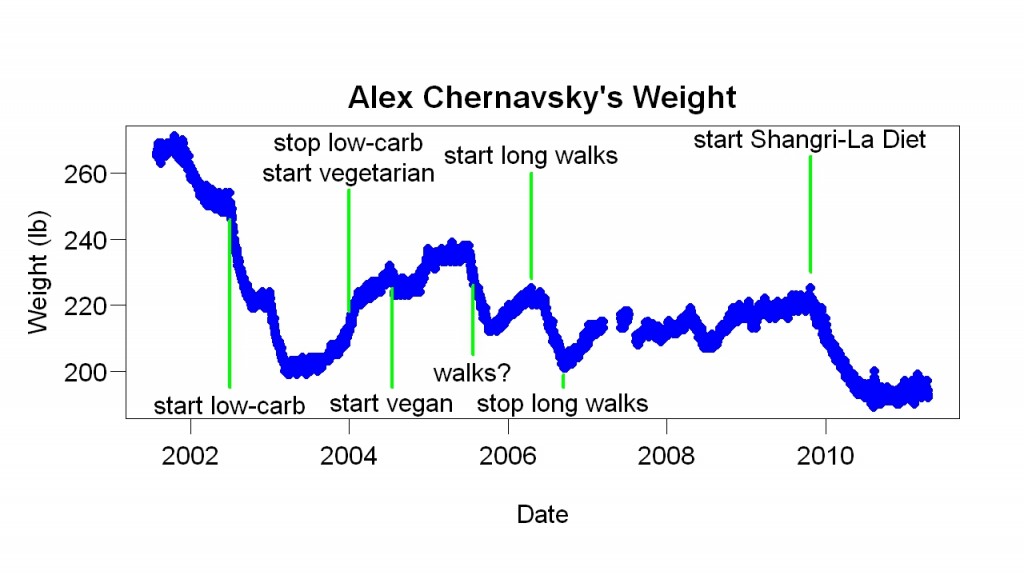

10 Years of Weight Measurements: What Was Learned

For ten years Alex Chernavsky has measured and recorded his weight (above). I asked what he learned from this. Here’s what he said:

I started the tracking because I thought that the very act of measuring (and recording) my weight every day would inspire me to lose weight. I don’t think it really worked that way, though. In order to lose weight, I had to take active measures.

What did I learn? I learned that low-carb diets work well in the short-run (as you said), and I also learned that eating low-carb is far, far easier than eating a calorie-restricted diet (which I’ve tried in the past, before I began recording my weight daily). I learned that regular exercise does lead to weight loss, although I can’t rule out a possible confounding factor: I wouldn’t be surprised if it turned out that I changed my eating habits at the same time that I started an exercise regime. That’s probably what Gary Taubes would claim.

I also learned that the Shangr-La diet works well for me. I think that the current upward trend is caused (at least in part) by the fact that I’m eating breakfast more and more often. I didn’t start eating breakfast until sometime last autumn. I will try eliminating breakfast again to see if it reverses the trend. I must say, though, that it’s a little difficult to watch my wife eating some scrumptious morning meal while I just drink coffee. The temptation is hard to resist.

I also learned that my weight fluctuates for no apparent reason at all. If you look at the period of roughly April 20, 2008 through mid-July 2008, you’ll see a drop of about ten pounds. I remember being surprised and puzzled during this time, because I could not think of any plausible reason why this weight loss would occur. I still don’t know. In any case, it was short-lived.

I also learned that I should have kept much better notes about what was going on during those ten years. I’m kicking myself now. I plan on continuing to collect data, and I will try to annotate the data better in the future.

My comments here.

Personal Science and Lyme Disease

Here is a website devoted to a new way to cure Lyme disease: ingesting large amounts of Vitamin C and salt. The website is vague about who made it but it certainly isn’t a for-profit enterprise. It begins:

After 13 years of suffering with Lyme disease, a possible cure has been stumbled upon. A cumulative effect of much research has produced the possibility that salt and vitamin C may be all that is needed to beat this elusive illness. Without going into a lot of detail, our theory is that Lyme is not just a bacterial disease, but also an infestation of microfilarial worms. . . From experimenting with the treatment of salt and vitamin C, we settled on a dosage of 3 grams of salt and 3,000 mg of vitamin C, each dose taken 4 times per day. . . . The Treatment can be grueling; taking it with food may aid in digestion. The results [= the improvement] should be almost instantaneous.

Unsurprisingly, people a naive person might think would be interested turned out to be not be interested:

We have tried on three occasions to get help [= interest in our findings] through the CDC to no avail. The responses were things such as: thanks, we’ll forward to a lyme researcher; or, we don’t accept contributions or downloads from individuals; or, these pictures are obviously fakes. . . . We tried the university routine. A public health researcher put us onto a microbiology chair, who sent us to a CDC parasitologist, who said he wasn’t a clinician and suggested a pathologist. . . . We tried the most noted lyme sites on the web. We were disappointed that most of them seem more concerned with fundraising than disease.

Which sounds like “we” is one person — a man. In any case, I hope “they” will allow outsiders to contribute experiences, perhaps by adding forums to the site. This is terrific work.

Effect of One-Legged Standing on Sleep

In 1996, I accidentally discovered that if I stood a lot I slept better. If I stood 9 hours or more, I woke up feeling incredibly rested. Yet to get any improvement I had to stand at least 8 hours. That wasn’t easy, and after about 9 hours of standing my feet would start to hurt. I stopped standing that much. It was fascinating but not practical.

In 2008, I accidentally discovered that one-legged standing could produce the same effect. If I stood on one leg “to exhaustion” — until it hurt too much to continue — a few times, I woke up feeling more rested, just as had happened when I stood eight hours or more. At first I stood with my leg straight but after a while my legs got so strong it took too long. When I started standing on one bent leg, I could get exhausted in a reasonable length of time (say, 8 minutes), even after many days of doing it.

This was practical. I’ve been doing it ever since I discovered it. A few months ago I decided to try to learn more about the details. I was doing it every day — why not vary what I did and learn more?

One thing I wanted to learn was: how much was best? I would usually do two (one left leg, one right leg) or four (two left leg, two right leg). Was four better than two? What about three?

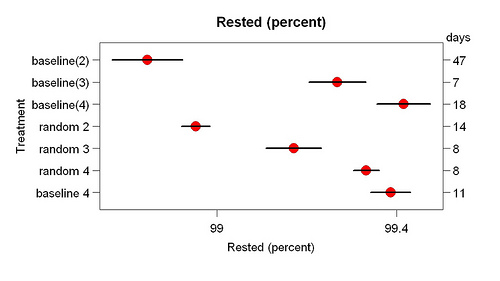

I decided to do something relatively sophisticated (for me): a randomized experiment. Every morning I would do two stands (one left, one right). In the evening I would randomly choose between zero, one, and two additional one-legged stands. Sometimes I forgot to choose. Here are the results for three sets of days: (a) “baseline” days (baseline(2), baseline(3), baseline(4)) before the randomized experiment and during the experiment when I forgot and (b) the “random” days (random 2, random 3, random 4) when I randomly choose and (c) a later set of days (“baseline 4″) when I did four one-legged stands every day.

Each morning, when I woke up I rated how rested I felt on a scale where 0 = not rested at all (as tired as when I went to sleep), and 100 = completely rested, not tired at all.

This shows means and standard errors. The number of days in each condition are on the right.

This shows means and standard errors. The number of days in each condition are on the right.

The main results are that three was better than two and four was better than three. The three/four difference was large enough compared to the two/four difference to suggest that five might be better than four. The similarity between random 4 and baseline 4 means that the amount of one-legged standing on previous days doesn’t matter much. For example, on Monday night it doesn’t matter how much I stood on Sunday.

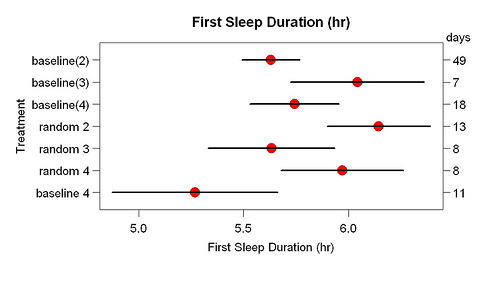

These differences were not reflected in how long I slept. Below are the results for “first” sleep duration, meaning the time from when I went to sleep to when I woke up for the first time — which is when I measured how rested I was (the graph above). On a small fraction of days, I went back to sleep a few hours later.

These results mean that one-legged standing increased how deeply I slept, what you could call sleep “efficiency”.

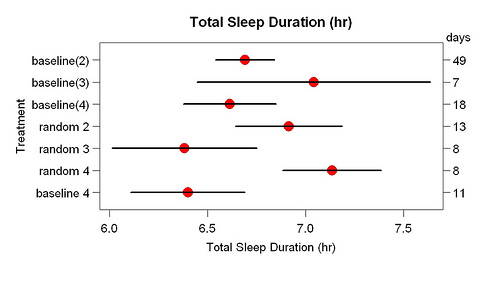

I also computed “total” sleep duration, which included first sleep duration, second sleep duration, and nap time the previous day (e.g., nap time on Monday plus sleep Monday night). If I took a long nap, I slept less that evening. Here are the results for total sleep duration.

The results also support the idea that one-legged standing made me sleep more deeply.

The randomized experiment had pluses and minuses compared to a simpler design (such as an ABA design, where you do each treatment for several days in a row). The two big pluses were that the conditions being compared were more equal and you could simply continue until the answer was clear. The two big minuses were that I often forgot to do the randomization and lack of realism. If I decided that four was the best choice, I’d do four every day, not in midst of two’s and three’s.

Overall, it was clear beyond any doubt that four was better than two, and clear enough that four was better than three (one-tailed p = 0.02). The results suggest trying larger doses, such as five and six. I’ve only done six once: before a flight from Beijing to San Francisco. It was one of the few long flights where I slept most of the way.

If you try this and you do more than one right and one left, leave plenty of time (two hours?) before the second pair, to allow the signaling molecules to be regenerated.

Terrific Essay by Cory Doctorow

I highly recommend this editorial by Cory Doctorow about the dangers of allowing a small number of people — such as big companies — to control how everyone’s computer, smart phone, etc., operates. I especially like his conclusion, modeled on Isaac Asimov’s T hree Laws of Robotics:

But we’ll only arrive at those solutions once we stop reflexively demanding limits on the general functionality of a PC and a network — and the sooner we do, the sooner we’ll legitimize a technology world whose first rule is “Obey your owner” and whose second rule is “Protect your owner’s interests”.

In case it isn’t obvious, self-experimentation and personal science increase your control of your body, just as Doctorow wants each person to control the technology they own. Without self-experimentation and personal science — and their ability to solve health problems in a way best for you — you give control over your body to doctors, drug companies, medical school professors, nutritionists, alternative-medicine advocates, and many others whose interests differ from yours. Often the difference is large — drug companies prefer expensive dangerous solutions to cheap safe ones.

Is Medical Research a Veblen Good?

Felix Salomon argues that fancy restaurants often manage to make their food a Veblen good — something that becomes more desirable when the price goes up. Restaurant food is a way to show off your wealth, in other words.

Veblen and I differ on the long-term value of Veblen goods. Veblen saw them as sort of ridiculous — which is why he coined the amusing term conspicuous waste. Whereas I see them as a way of promoting innovation: Long ago, desire for luxury goods, goods with “wasteful” features, helped the most skilled artisans make a living. These artisans were the best source of innovation within a society.

Unfortunately everyone likes to show off, not just fancy-restaurant-goers. Throughout the medical research community, there is an obvious preference for expensive research over cheaper research. (I’m not saying experimental psychologists such as me are any better: We’re not.) Few medical researchers understand that expensive studies are a last resort and the larger your sample size, the less you understand what you are studying. (Experimental psychologists do understand this.) When people doing research related to health are too concerned with showing off (e.g., doing studies that require expensive equipment) to do effective research, the benefit-cost ratio of Veblenian behavior goes below one. Desire to show off gets in the way of solving health problems. This is why personal science — using science to solve your own problems — is so important: The personal scientist will do whatever works, regardless of how impressive it is.