My personal science introduced me to a research method I have never seen used in research articles or described in discussions of scientific method. It might be called wait and see. You measure something repeatedly, day after day, with the hope that at some point it will change dramatically and you will be able to determine why. In other words: 1. Measure something repeatedly, day after day. 2. When you notice an outlier, test possible explanations. In most science, random (= unplanned) variation is bad. In an experiment, for example, it makes the effects of the treatment harder to see. Here it is good.

Here are examples where wait and see paid off for me:

1. Acne and benzoyl peroxide. When I was a graduate student, I started counting the number of pimples on my face every morning. One day the count improved. It was two days after I started using benzoyl peroxide more regularly. Until then, I did not think benzoyl peroxide worked well — I started using it more regularly because I had run out of tetracycline (which turned out not to work).

2. Sleep and breakfast. I changed my breakfast from oatmeal to fruit because a student told me he had lost weight eating foods with high water content (such as fruit). I did not lose weight but my sleep suddenly got worse. I started waking up early every morning instead of half the time. From this I figured out that any breakfast, if eaten early, disturbed my sleep.

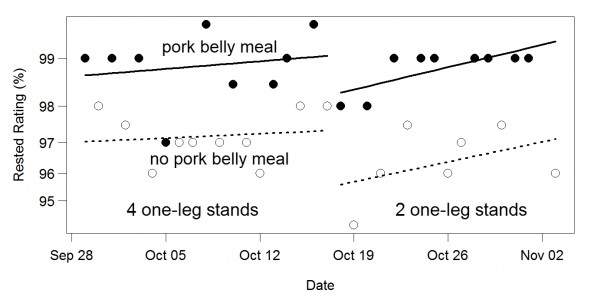

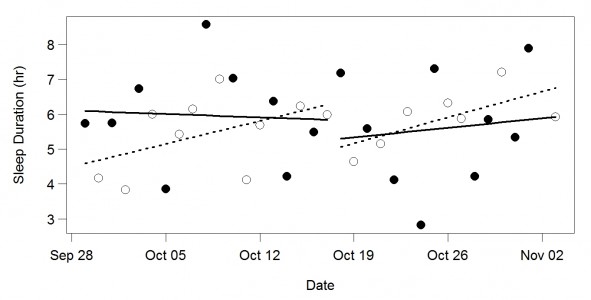

3. Sleep and standing (twice). I started to stand a lot to see if it would cause weight loss. It didn’t, but I started to sleep better. Later, I discovered by accident that standing on one leg to exhaustion made me sleep better.

4. Brain function and butter. For years I measured how fast I did arithmetic. One day I was a lot faster than usual. It turned out to be due to butter.

5. Brain function and dental amalgam. My brain function, measured by an arithmetic test, improved over several months. I eventually decided that removal of two mercury-containing fillings was the likely cause.

6. Blood sugar and walking. My fasting blood sugar used to be higher than I would like — in the 90s. (Optimal is low 80s.) Even worse, it seemed to be increasing. (Above 100 is “pre-diabetic.”) One day I discovered it was much lower than expected (in the 80s). The previous day I had walked for an hour, which was unusual. I determined it was indeed cause and effect. If I walked an hour per day, my fasting blood sugar was much better.

This method and examples emphasize the point that different scientific methods are good at different things and we need all of them (in contrast to evidence-based medicine advocates who say some types of evidence are “better” than other types — implying one-dimensional evaluation). One thing we want to do is test cause-effect ideas (X causes Y). This method doesn’t do that at all. Experiments do that well, surveys are better than nothing. Another thing we want to do is assess the generality of our cause-effect ideas. This method doesn’t do that at all. Surveys do that well (it is much easier to survey a wide range of people than do an experiment with a wide range of people), multi-person experiments are better than nothing. A third thing we want to do is come up with cause-effect ideas worth testing. Most experiments are a poor way to do this, surveys are better than nothing. This method is especially good for that.

The possibility of such discoveries is a good reason to self-track. Professional scientists almost never use this method. But you can.