In 2007, Jon Cousins started tracking his mood to help NHS psychiatrists decide if he was cyclothymic (a mild form of bipolar disorder). After a few months of tracking, he started sharing his scores with a friend, who expressed concern when his score was low. Jon’s mood sharply improved, apparently because of the sharing. This led him to start Moodscope, a website that makes it easy to track your mood and share the results.

I was curious about the generality of what happened to Jon — how does sharing mood ratings affect other people? In January, Jon kindly posted a short survey about this. More than 100 people replied.

Their answers surprised me. First, in a survey about sharing your mood — not about tracking your mood — most respondents did not share their mood. It is as if, in a survey about being tall, most respondents were not tall. Second, although Jon’s mood sharply rose as soon as he started sharing, this was not the usual experience. Sharing helped, some people said, but other people said sharing hurt. For example, one person said her mood was used against her in arguments. Finally, the respondents gave all sorts of persuasive reasons that rating their mood helped them. To me, at least, the value of mood rating isn’t obvious. I can list a dozen hypothetical benefits but whether they actually happen is unclear to me. I rated my mood for years and did it only to learn about the effects of morning faces. MoodPanda, another mood-rating site, gives a few brief vague unenthusiastic reasons to track your mood. And their site is all about mood rating.

In contrast, Moodscope users were clear and enthusiastic about the value of tracking. Here are some reasons they liked mood-tracking:

It is useful to look back sometimes to help you find ways of ‘keeping up’ a positive mood/outlook.

My mood range has definitely narrowed since starting mood stabilizers, so using Moodscope has given me solid evidence that the treatment is working well. I also run statistical analyses of my mood charts against variables like sleep, medication use, and alcohol consumption. The correlations were not particularly meaningful using a 9-point Likert-like scale from a standard mood chart. When I used my Moodscope scores instead, I suddenly found that some of the correlations are (ridiculously!) statistically significant, which also made me feel more certain about what I need to do and change to better manage my mental health.

I could express my miserableness in total safety, without leaning on anybody else. It has proved wonderful. My profile has risen from a score of 7 on day 1 (11 months ago) to the 90s now. Being able to track my reasons for feeling better or worse has been part of this. The patterns are visible, ditto the triggers that send me up or down.

The great benefit of Moodscope has been to confirm the advantages of my own lifestyle management for coping with bipolar disorder. It has shown that what I felt was bad for me, is indeed bad, and what I felt was good for me, is indeed good. (I know that I have to take the meds.)

It helps that I can post things about sleep hours in the comments and see the correlation to the chart.

I have found the tool immensely helpful in gaining insight into how my own behaviour and thoughts can impact upon my mental health. I have gained more control.

It helps me to gain insight into my moods, take responsibility for them and steer a calmer, more productive course through life.

It allows me not to panic when I am low as I can see that ups and downs are all part of life.

Pre-Moodscope, I would not realize i was on the way down until 10 or so days had passed, and so I had done nothing. But with Moodscope, I can see if it’s a trend and do something immediately. It means I deliberately intervene earlier.

I use my scores, and comments, to understand what triggers my low mood and take steps to stop it getting lower, in so far as I am able.

I view it as a diary of sorts, private for my own contemplation.

I want to catch myself before I make a deep plunge and stay down too long. I do use the info with my doctor. I love having something concrete to show and talk about.

It has helped me feel like there is a greater safety net there, and given me a greater awareness of when I’m slipping back into my treacle pit; I now know that any score between 20 and 30 means I am in dangerous territory and need to take some remedial action, and if I get below 20 then I’m really in a bad way.

Moodscope has helped me identify incidents in my life with my mood. For example if I have to assert myself strongly with someone, I feel exhilarated and very proud of myself for about two day then gradually my mood will lower and a week later I will feel apathetic and down. I love that it is helping me make sense of my emotions and as a result I am not judgmental of them.

I’ve found Moodscope really useful in finding out what influences my moods. I am bipolar and after 20 years on lithium I’m managing without any meds. Don’t worry, I came off it slowly, under medical supervision!

I use Moodscope as a sort of diary of how I am feeling. Looking back I can see what really pushed my mood down and oddly it’s not always the major things that you’d imagine. In my case depression is brought on more by physical health problems – I am a CFS sufferer.

I sum up their reasons like this: 1. Helps understand causality (what causes mood to be low or high?). 2. Immediate guidance (should I take action to raise it?). 3. Self-expression (similar to diary). 4. Reassurance (low moods are “part of life”). Alexandra Carmichael wrote about the value of mood-tracking and mood-sharing. Her experience did not repeat Jon’s: She found little initial benefit of sharing, but great eventual benefits (“a kind of deep, healing therapy”). This was the main benefit of tracking for her — that it allowed this sharing. Kari Sullivan also tried Moodscope. She didn’t share her mood. The benefits she list fall under the heading of Reason #1 (helps understand causality). For example, she learned “most social interaction lowers my mood,” which surprised her.

Not everyone liked tracking:

My girlfriend . . . stopped using Moodscope. In her words, “I don’t want Moodscope to remind me how terrible I’m doing.”

She has now decided to give up on taking the test as it just reinforces her feelings of general greyness and sometimes despair.

At a website devoted to collecting new ideas about health, Moodscope ranked #1 out of about 500 ideas.

When I started my self-experimentation I didn’t get anywhere for a long time (after initial success with acne). After 1990, however, I was astonished at the progress I made. One useful discovery after another — how to lose weight, sleep better, be in a better mood, and so on. Over the next 20 years, I improved my health considerably more than all the other scientists in the world put together. I came to see what was happening as a kind of catalysis. The useful information was already there; my personal science was the catalyst that turned it into something useful. (Lack of people like me was why the discoveries were so abundant — a counter-example to Tyler Cowen’s lack-of-low-hanging fruit explanation for stagnation.) Professional scientists were too restricted in what they did.

The Moodscope story is similar. Psychologists have been studying and measuring mood for a long time. The Profile of Mood States is an important result of their research. But no psychologist saw it as an agent of change. It was simply a research tool, albeit a popular one. Only when Jon Cousins started using it for his own selfish purposes did it become clear how useful it could be. He was the catalyst.

Both my story and Jon’s are examples of what I say about DIYization of science: It gets tools into the hands of a larger and more diverse group of possible innovators, who are less “stuck” — less committed to old ways of doing things — than the professionals. They are also more motivated to do something useful than the professionals, who are weighed down with other big concerns — about status, job security, money, and so on.

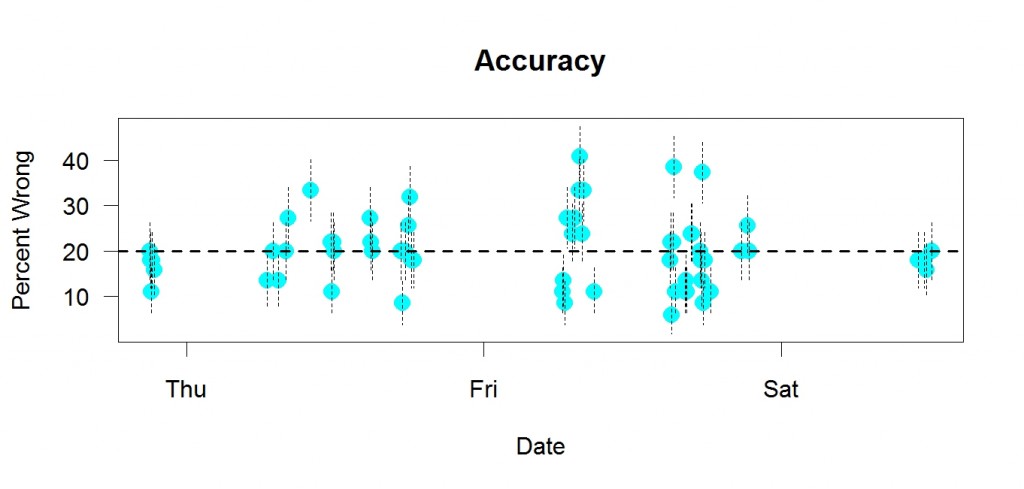

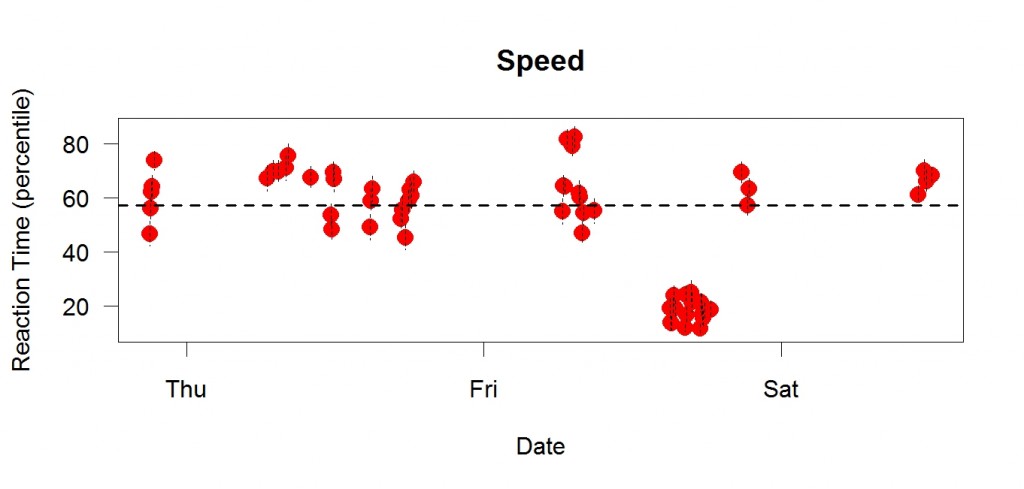

This is me a few days ago. I did a choice reaction time task many times. Each dot is a session with enough trials to supply 32 correct answers.The y axis is in “percentile” units, meaning speed relative to recent performance. If my speed was at the average of recent performance, the percentile would be 50, for example. Higher percentiles = better performance = faster (shorter reaction time). Each point is a mean; the vertical bars are standard errors. The dotted line is the median of the means.

This is me a few days ago. I did a choice reaction time task many times. Each dot is a session with enough trials to supply 32 correct answers.The y axis is in “percentile” units, meaning speed relative to recent performance. If my speed was at the average of recent performance, the percentile would be 50, for example. Higher percentiles = better performance = faster (shorter reaction time). Each point is a mean; the vertical bars are standard errors. The dotted line is the median of the means.