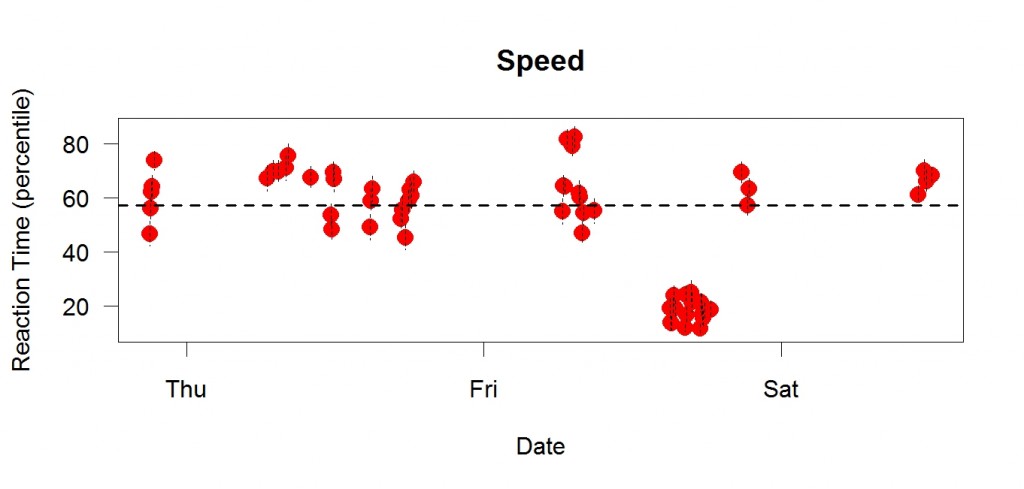

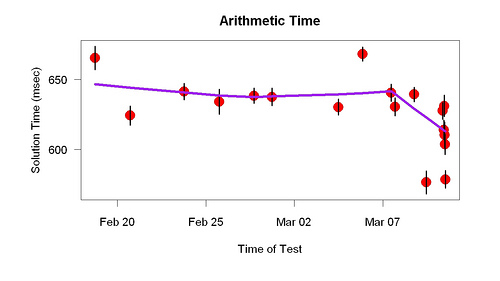

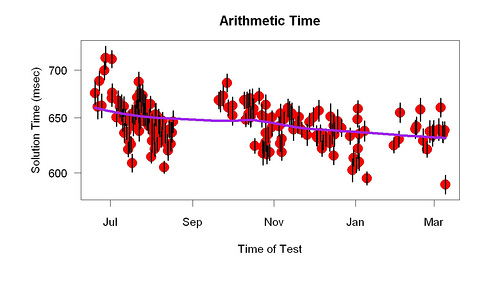

This is me a few days ago. I did a choice reaction time task many times. Each dot is a session with enough trials to supply 32 correct answers.The y axis is in “percentile” units, meaning speed relative to recent performance. If my speed was at the average of recent performance, the percentile would be 50, for example. Higher percentiles = better performance = faster (shorter reaction time). Each point is a mean; the vertical bars are standard errors. The dotted line is the median of the means.

This is me a few days ago. I did a choice reaction time task many times. Each dot is a session with enough trials to supply 32 correct answers.The y axis is in “percentile” units, meaning speed relative to recent performance. If my speed was at the average of recent performance, the percentile would be 50, for example. Higher percentiles = better performance = faster (shorter reaction time). Each point is a mean; the vertical bars are standard errors. The dotted line is the median of the means.

The graph shows that Friday afternoon I was suddenly unusually slow. After dinner, I returned to normal. A change from 60%ile to 20%ile to 60%ile resembles an IQ change from 105 to 87 to 105 (an 18-point change).

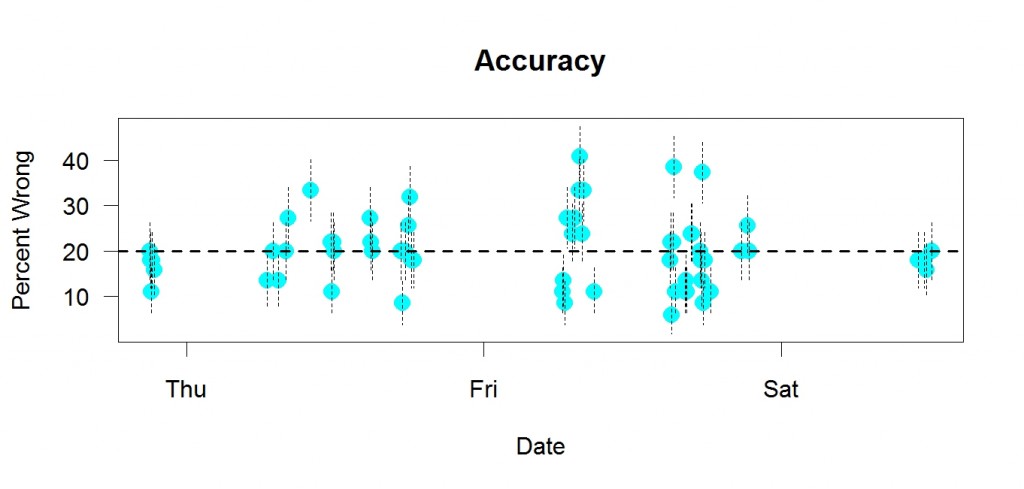

At the same time accuracy was roughly constant:

Because accuracy was roughly constant, the change in speed was not due to a shift on a speed-accuracy tradeoff function.

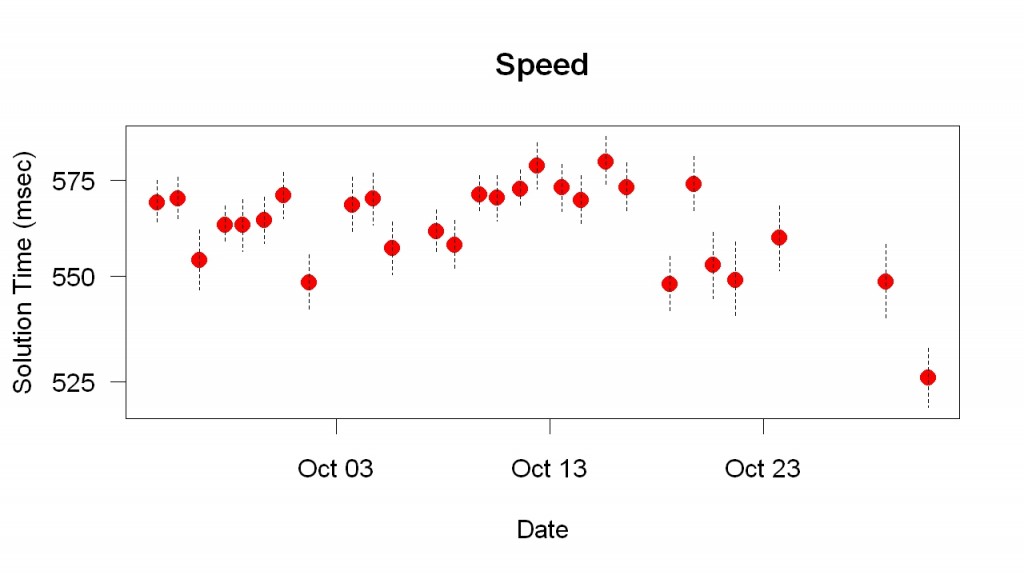

There are two puzzles here. 1. Why were my scores low Friday afternoon? 2. Why did they recover after dinner? On Friday I didn’t feel well. As a result, I didn’t eat much. Maybe my blood sugar was lower than usual. I usually eat 30 g butter twice/day. On Friday I didn’t have any. At dinner I did have moderate amounts of pork fat (but not butter) and sugar (in lemon citron tea). Friday 6 pm I had a cup of black tea. Although I haven’t noticed effects of tea on these scores, there’s a first time for everything.

Here is a clue to what makes my brain work well (= fast), I conclude. Butter causes sudden improvement, I have found; which makes it plausible that lack of butter (and other animal fat) could cause sudden degradation. Another possibility was that my blood sugar was low Friday afternoon. (I didn’t think of this at the time, and didn’t measure it.) I’m surprised that something as important as brain function would be as fragile as these results imply. When various nutrient deficiencies are studied with conventional measures, it generally takes weeks or months without the nutrient for the bad effects to become apparent. It takes many weeks without Vitamin C to get scurvy, for example.

These results raise the intriguing possibility that everyone has sudden ups and downs in brain function and that these ups and downs can be detected at high signal/noise ratios. If so, we can use these ups and downs to learn how to make our brains work well. These results also imply — because my choice reaction time test required only a laptop — that anyone can detect them, study them, and learn what causes them. No experts needed. What a change that would be.

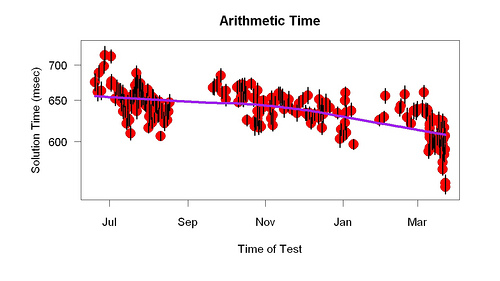

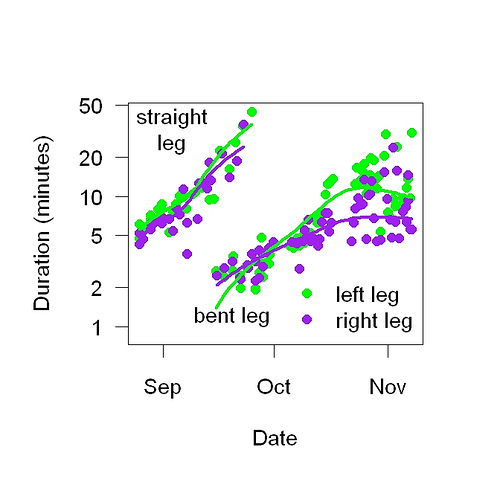

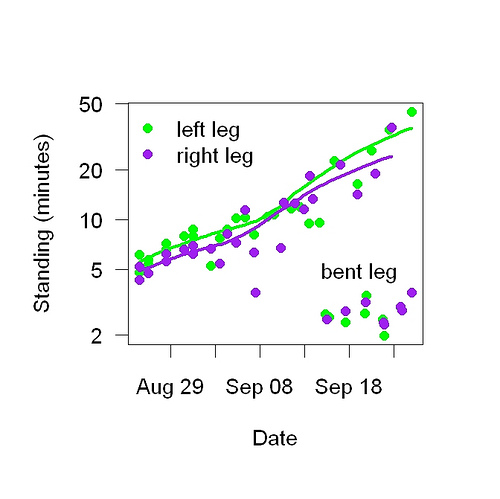

Each point is a different bout of one-legged standing. Most of the points are from bouts where the standing leg was straight or bent (usually straight) but a few of them (“bent leg”) are from bouts where the standing leg was bent the whole time. Most days have two bouts: 1. On the left leg until I get tired. 2. On the right leg until i get tired. I’m pretty sure there’s no effect until it becomes difficult — until the muscles are so stressed that they send out a grow signal. The whole thing is pleasant because I watch TV or a movie at the same time but, as the graph shows, it has become seriously time-consuming.

Each point is a different bout of one-legged standing. Most of the points are from bouts where the standing leg was straight or bent (usually straight) but a few of them (“bent leg”) are from bouts where the standing leg was bent the whole time. Most days have two bouts: 1. On the left leg until I get tired. 2. On the right leg until i get tired. I’m pretty sure there’s no effect until it becomes difficult — until the muscles are so stressed that they send out a grow signal. The whole thing is pleasant because I watch TV or a movie at the same time but, as the graph shows, it has become seriously time-consuming.