From an excellent Atlantic article about John Ioannidis, who has published several papers saying that medical research is far less reliable than you might think:

A different oak tree at the site provides visitors with a chance to try their own hands at extracting a prophecy. “I [bring] all the researchers who visit me here, and almost every single one of them asks the tree the same question,” Ioannidis tells me . . . “’Will my research grant be approved?'”

A good point. I’d say his main contribution, based on this article, is pointing out the low rate of repeatability of major medical findings. Until someone actually calculated that rate, it was hard to know what it was, unless you had inside experience. The rate turned out to be lower than a naive person might think. It was not lower than an insider might think, which explains lack of disagreement:

David Gorski . . . noted in his prominent medical blog that when he presented Ioannidis’s paper on [lack of repeatability of] highly cited research at a professional meeting, “not a single one of my surgical colleagues was the least bit surprised or disturbed by its findings.”

I also like the way Ioannidis has emphasized the funding pressure that researchers face, as in that story about the oak tree. Obviously it translates into pressure to get positive results, which translates into overstatement.

I also think his critique of medical research has room for improvement:

1. Black/white thinking. He talks in terms of right and wrong. (“We could solve much of the wrongness problem, Ioannidis says, if the world simply stopped expecting scientists to be right. That’s because being wrong in science is fine.”) This is misleading. There is signal in all that medical research he criticizes; it’s just not as strong a signal as the researchers claimed. In other words the research he says is “wrong” has value. He’s doing the same thing as all those meta-analyses that ignore all research that isn’t of “high quality”.

2. Nihilism (which is a type of black/white thinking). For example,

How should we choose among these dueling, high-profile nutritional findings? Ioannidis suggests a simple approach: ignore them all.

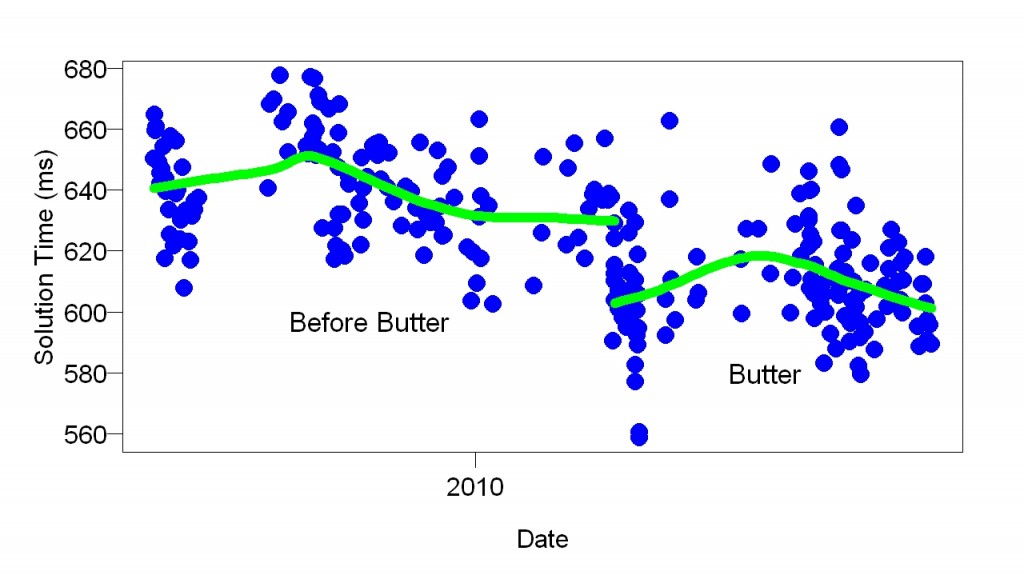

I’ve paid a lot of attention to health-related research and benefited greatly. Many of the treatments I’ve studied through self-experimentation were based on health-related research. An example is omega-3. There is plenty of research suggesting its value and this encouraged me to try it. Likewise, there is plenty of evidence supporting the value of fermented foods. That evidence and many other studies (e.g., of hormesis) paint a large consistent picture.

3. Bias isn’t the only problem, but, in this article, he talks as if it is. Bias is a relatively minor problem: you can allow for it. Other problems you can’t allow for. One is the Veblenian tendency to show off. Thus big labs are better than small ones, regardless of which would make more progress. Big studies better than small, expensive equipment better than cheap, etc. And, above all, useless is better than useful. The other is a fundamental misunderstanding about what causes disease and how to fix it. A large fraction of health research money goes to researchers who think that studying this or that biochemical pathway or genetic mechanism will make a difference — for a disease that has an environmental cause. They are simply looking in the wrong place. I think the reason is at least partly Veblenian: To study genes is more “scientific” (= high-tech = expensive) than studying environments.

Thanks to Gary Wolf.