Warning: This post, written for the Quantified Self blog, has more repetition than usual of material in earlier posts.

Warning: This post, written for the Quantified Self blog, has more repetition than usual of material in earlier posts.

In January, after talking with Matthew Cornell, I decided to measure my work habits. I typically work for a while (10-100 minutes), take a break (10-100 minutes), resume work, take another break, and so on. The breaks had many functions: lunch, dinner, walk, exercise, nap. I wanted to do experiments related to quasi-reinforcement.

I wrote R programs to record when I worked. They provided simple feedback, including how much I had worked that day (e.g., “121 minutes worked so far”) and how long the current bout of work had lasted (e.g., “20 minutes of email” — meaning the current bout of work, which was answering email , had so far lasted 20 minutes).

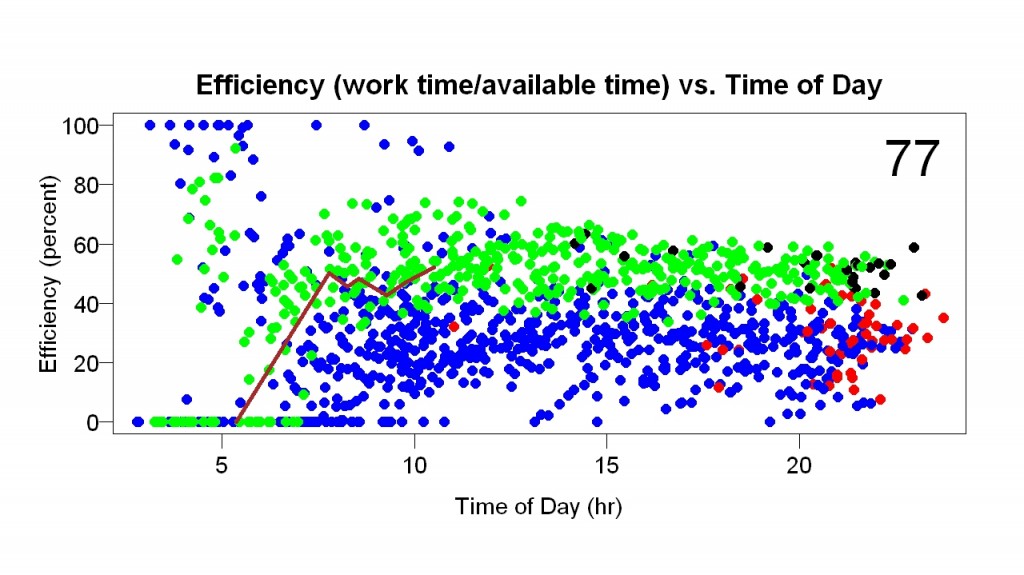

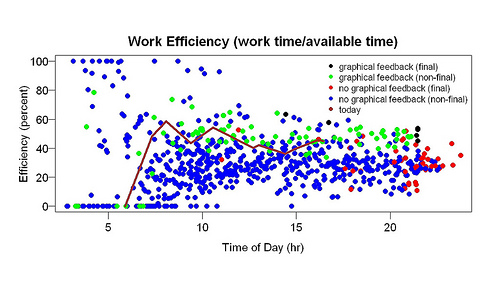

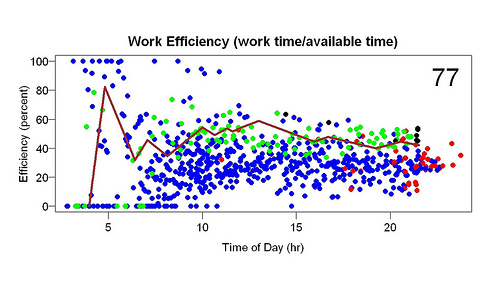

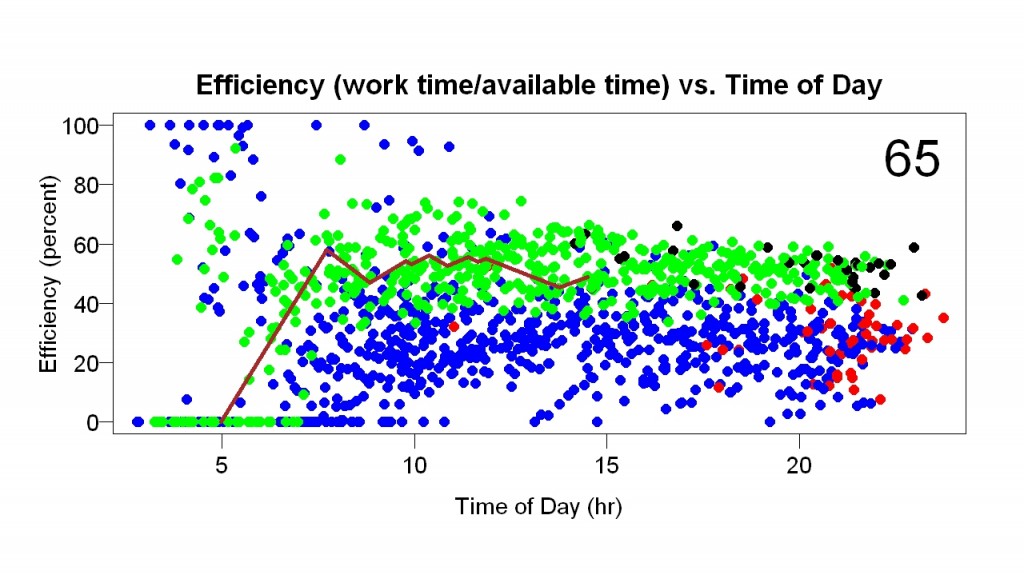

I collected data for two months before I wrote programs to graph the data. The first display I made (example above) showed efficiency (time spent working/time available to work) as a function of time of day. Available time started when I woke up. If I woke up at 5 am, and by 10 am had worked 3 hours, the efficiency at 10 am would be 60%. The display showed the current day as a line and previous days as points. During the day the line got longer and longer.

The blue and red points are from before the display started; the green and black points are from after the display started. The red and black points are the final points of their days — they sum up the days. A week or so after I made the display I added the big number in the upper-right corner (in the example, 65). It gives the percentile of the current efficiency compared to all the efficiency measurements within one hour of the time of day (e.g., if it is 2 p.m., the current efficiency is compared to efficiency measurements between 1 p.m. and 3 p.m. on previous days).

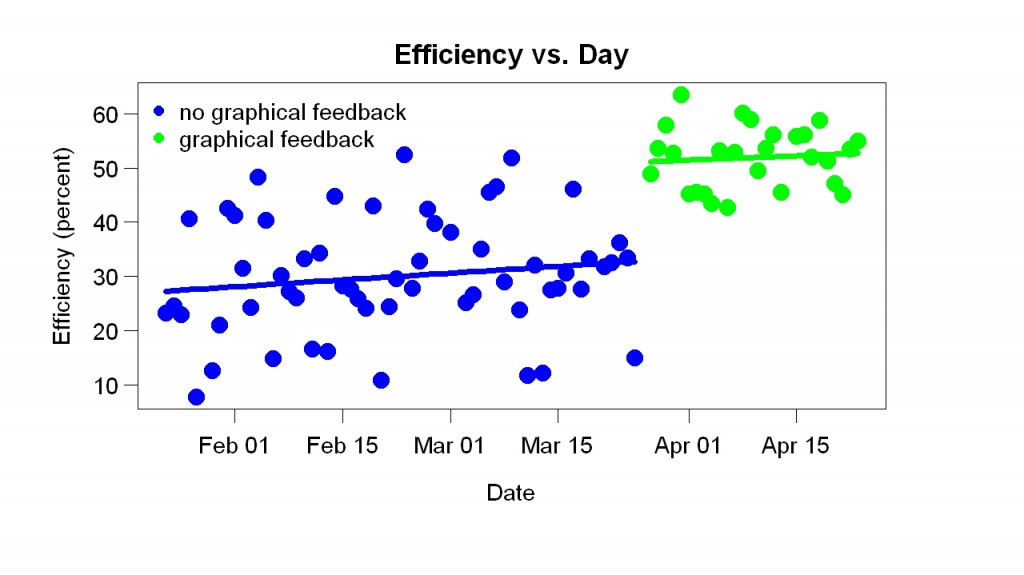

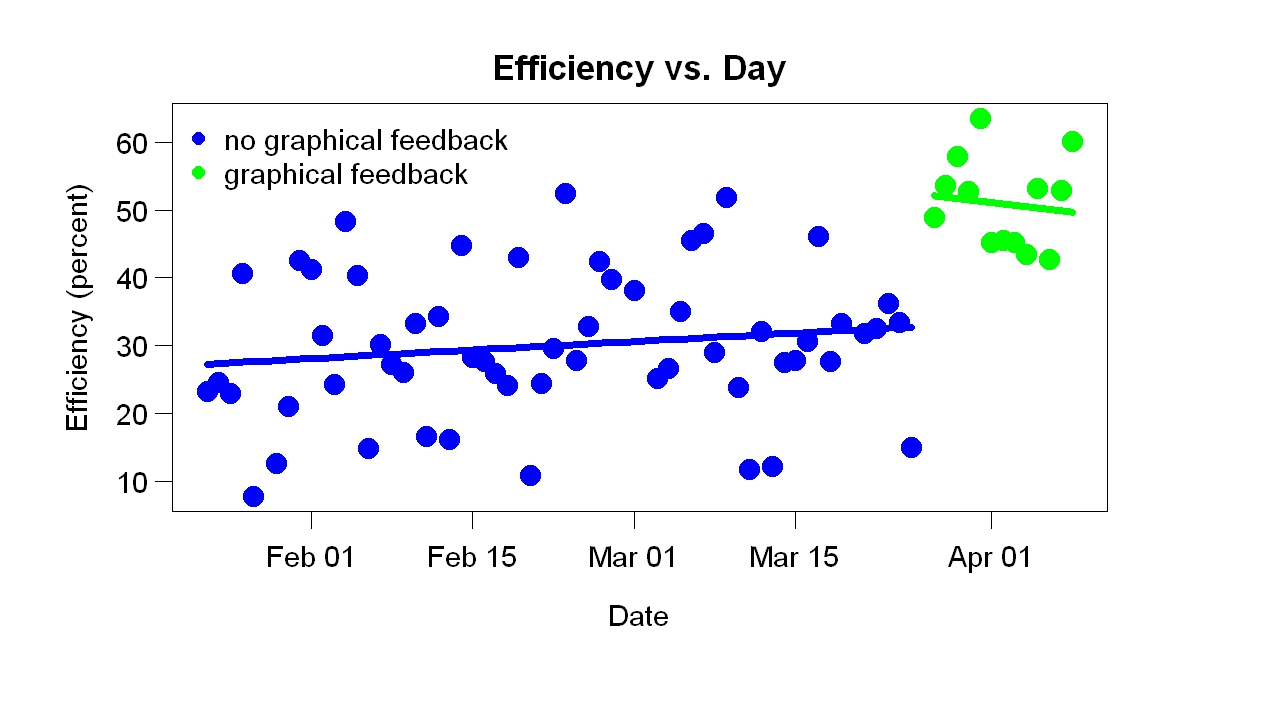

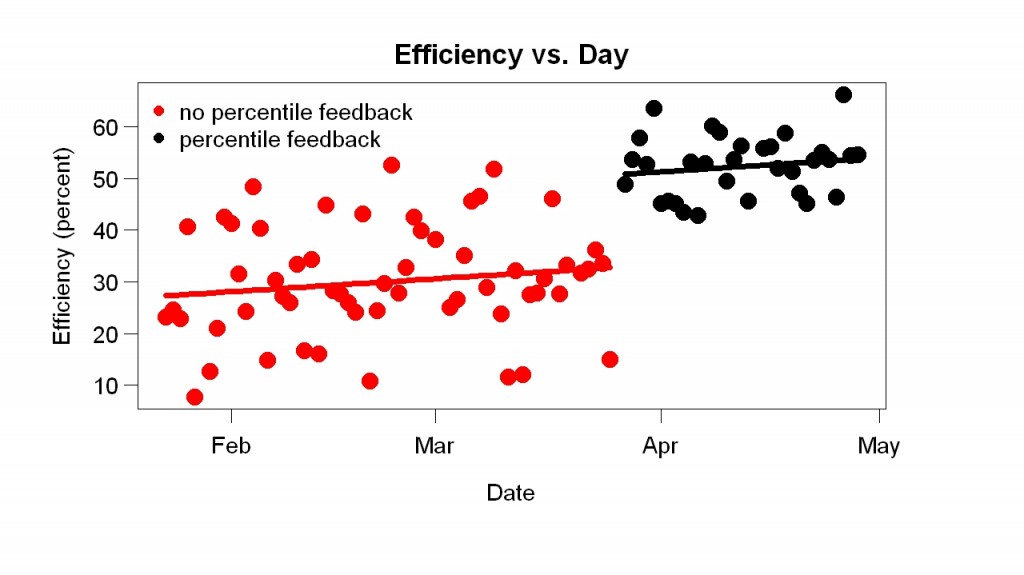

I started looking at the progress display often. To my great surprise, it helped a lot. It made me more efficient. You can see this in the example above because most of the green points (after the display started) are above most of the blue points (before the display). You can also see the improvement in the graph below, which shows the final efficiency of each day.

My efficiency jumped up when the display started.

Why did the display help? I call it percentile feedback because that name sums up a big reason I think it helped. The number in the corner makes the percentile explicit but simply seeing where the end of the line falls relative to the points gives an indication of the percentile. I think the graphical display helped for four reasons:

1. All improvement rewarded, no matter how small or from what level. Whenever I worked, the line went up and the percentile score improved. Many feedback schemes reward only a small range of changes of behavior. For example, suppose the feedback scheme is A+, A, A-, etc. If you go from low B- to high B-, your grade won’t change. A score of 100 was nearly impossible, so there was almost always room for improvement.

2. Overall performance judged. I could compare my percentile score to my score earlier in the day (e.g., 1 pm versus 10 am) but the score itself was a comparison to all previous days, in the sense that a score above 50 meant I was doing better than average. Thus there were two sources of reward: (a) doing better than a few hours ago and (b) doing better than previous days.

3. Attractive. I liked looking at the graphs, partly due to graphic design.

4. Likeable. You pay more attention to someone you like than someone you don’t like. The displays were curiously likable. They usually praised me, in the sense that the percentile score was usually well above 50. Except early in morning, they were calm, in the sense that they did not change quickly. If the score was 80 and I took a 2-hour break, the score might go down to 70 — still good. And, as I said earlier, every improvement was noticed and rewarded — and every non-improvement was also gently noted. It was as if the display cared.

Now that I’ve seen how helpful and pleasant feedback can be, I miss similar feedback in other areas of life. When I’m walking/running on my treadmill, I want percentile feedback comparing this workout to previous ones. When I’m studying Chinese, I want some sort of gentle comparison to the past.