Andrew Gelman links to this post about intellectual working conditions. It reminds me of something I do every day that still amuses me. I keep track of whether I am working or not — and I count making tea as working. This helps me get started: I start by making tea. The opportunity to mislead myself (appear more efficient than I am, get something for nothing) makes me want to start working.

Category: self-experimentation

Beijing Smog: Good or Bad?

I am in Beijing. The smog is bad. It is more humid than usual and the air is dirtier than usual. At his blog, James Fallows, who is also in Beijing, has posted pictures and pollution measurements. (Incidentally, Eamonn Fingleton, an excellent writer, will be guest-blogging there. In Praise of Hard Industries is one of the best business/economics books I’ve read.)

The effect of smog on health isn’t obvious. Maybe you know about hormesis — the finding that a small dose of a poison, such as radioactivity, is beneficial. It has been observed in hundreds of experiments. It makes sense: the poisons activate repair systems. Even if you know about hormesis, you probably don’t know that one of the first studies of smoking and cancer found that inhaling cigarette smoke appeared beneficial: inhalers had less cancer than non-inhalers. R. A. Fisher, the great statistician, emphasized this (pp. 160-161):

There were fewer inhalers among the cancer patients than among the non-cancer patients. That, I think, is an exceedingly important finding.

This difference (a negative correlation) appeared in spite of two positive correlations: Heavy smokers get more cancer than light smokers; and heavy smokers are more likely to inhale than light smokers. It is far from the only fact suggesting the connection between smoking and health isn’t simple.

So I am not worried about Beijing smog. The real danger, I think, is not eating fermented foods. Which, thankfully, is infinitely more under my control.

Meat-Only Diet: Crave Carbs. Meat + Egg: No Craving

Joseph Buchignani, a businessman in Shenzhen, has suffered from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) since he was a teenager. He is now in his 20s. By trial and error, he discovered that a meat-only diet eliminated his IBS. However, it also caused craving for carbs. Because carbs caused IBS, he couldn’t simply eat carbs. He tried many ways of getting rid of the craving for carbs: eating more animal fat, eating less animal fat, eating oil, eating lard, and eating different kinds of animals and cuts of meat. He varied how he cooked the meat, eating especially fresh meat, and eating fresh whole fish. All of these attempts failed. He did not try taking a multivitamin pill.

Finally he tried adding egg to the meat. That eliminated his craving for carbs. It made his diet much more sustainable.

This is fascinating for four reasons.

1. Sure, some cravings reflect nutrient deficiencies. (Not all cravings: An alcoholic craves alcohol.) But in the cases I know about, there is an obvious or semi-obvious connection between the craving and the deficiency. For example, people who chew too much ice (pagophagia) crave ice to chew. They are iron-deficient. Eating iron eliminates the pagophagia. Long ago, a craving to eat something crunchy would have led you to eat bones. Bone marrow is high in iron. So the craving makes sense. In contrast, there is no obvious or semi-obvious connection between carbs and eggs.

2. It suggests that a paleo diet is a good place to start looking for the ideal diet. Paleo ideas suggest a high-meat diet. But no matter how long you study what Stone-Age people ate, you will not figure out that eggs will eliminate carb cravings.

3. Like many people, especially those doing paleo, I eat mostly meat and vegetables (a conventional low-carb diet). Unlike most low-carbers, I also eat lots of fermented foods. I don’t crave carbs, perhaps because of the lactose in yogurt or the sucrose in kombucha. It hadn’t occurred to me to start eating eggs regularly but Joseph’s discovery suggests I should try it.

4. Joseph’s personal science led him to discover something highly useful and completely non-obvious.

Walking and Learning Update

I discovered a year ago that walking makes it pleasant to study boring stuff — as I put it then, boring + boring = pleasant. I am still a little amazed.

Like any scientific discovery, I suppose, I had to do serious engineering to make good use of it. In particular:

1. Make walking easier. I use a treadmill in my apartment, which eliminates travel time (to where I do it), eliminates distractions, provides climate control, and allows me to walk barefoot.

2. Steady stream of study materials. Now I am using an Anki deck of Chinese characters put together by someone else. This saves a lot of time. (Anki is an open-source version of SuperMemo, a flashcard program that tries to optimize repetition.)

3. Figure out how much new stuff to study each day. Without plenty of repetition, you are wasting your time — you will forget what you’ve learned. Most of a study session is repetition. This means it’s not obvious how much new material to introduce each day. I found that 10 new Chinese characters is about right.

4. Put laptop on treadmill. To use Anki while on my treadmill, I need to use my laptop on my treadmill. At the Beijing Wal-mart, I found a piece of Sunor metal shelving that works perfectly. I put the shelf (about 90 cm long) across the arms of the treadmill, put the laptop on the shelf.

5. Minimize complications. I first noticed the effect using Anki. But Anki had several features I disliked, so I switched to ordinary flashcards. But they were too complicated — hard to schedule appropriately (you need to slowly expand the time between tests), time-consuming to keep track of progress. I had to keep stopping to make marks on the cards. So I am back to using Anki. Anki lacks a graph of progress — a graph that shows amount of learning versus date. But it is better than flashcards.

Each improvement made things better. With all of them, I lose track of time. Study, study, study, walk, walk, walk. Then it’s over. Not just painless, pleasant — different than any pleasure I have felt before. It feels a little like a new energy source (I imagine it can be used to learn many things), a little like teleportation.

The science aspect of it also interests me. Learning is the core topic of experimental psychology. Thousands of experiments have been done about human learning, thousands more about animal learning. Experimental psychologists are good methodologists; the average experimental psychology experiment makes the average medical-school experiment look retarded. But the walking/learning effect (walking makes learning pleasant) is outside anything anyone has ever reported. Only Michel Cabanac (not an experimental psychologist) has studied how variation in pleasantness regulates action (e.g., eating). Experimental psychologists lack good ways to find new effects. By missing this effect, they are missing a bigger idea:Â learning is regulated, just as a thousand other things inside our bodies are regulated.

Walking and Learning

A new study supports my idea that walking and learning are connected. Normally I found it boring to study Chinese flash cards. While walking, I found it pleasant. You could say walking made me more curious. Just standing on the treadmill didn’t have this effect.

The study divided men and women in their 60′s into two groups: (a) walking for 40 minutes/day and (b) stretching. At the end of the study, for persons in the walking group, part of the hippocampus — which is associated with learning — had grown. For persons in the other group, that part of the hippocampus got smaller. Several other parts of the brain, not associated with learning, did not differ between the groups.

Chairs: The Carbohydrate of Furniture

In the excellent BBC series about the history of design (The Genius of Design), chairs played a large role. Perhaps a fifth of the show is about them, far more than any other product. Yet I rarely use them and own only a few. I sit while socializing but otherwise usually work reclining (on a bed or in a rocking chair) or standing up. Long ago I discovered that if I stand a lot I sleep better. Since then I’ve spent a lot of time on my feet for someone whose job doesn’t require it.

My self-experimental discoveries led me to avoid about 99% of the food sold in a typical store — granola, cake mixes, flour, rice, breakfast cereals, and so on. Most of what I avoid is carbohydrate. Just as we are pushed to sit in chairs, we are pushed to eat carbohydrate. I don’t think carbs cause obesity — it’s more complicated than that — but they raise blood sugar (making diabetes more likely) and rarely supply essential fats. They are also poor source of microbes, which I’m sure you need to eat.

Over the last 30 years, designers have focused more and more on sustainability, “green design”, and so on. I think of this as the second half of the industrial revolution — cleaning up the mess. As far as I can tell, designers have not yet started to understand that we need certain things from our environment just as we need certain things from our food. Here are some things I think we need from our environment: 1. Sunlight in the morning. Some buildings have daylighting to save energy. 2. Faces in the morning. 3. Absence of fluorescent lights at night. 4. Movement throughout the day. 5. An hour of walking per day.

Growth of Quantified Self

The first Quantified Self (QS) Meetup group met in Kevin Kelly’s house near San Francisco in 2008. I was there; so was Tim Ferriss. Now there are 19 QS groups, as distant as Sydney and Cape Town.

I believe this is the beginning of a movement that will greatly improve human health. I think QS participants will discover, as I did, that simple experiments can shed light on how to be healthy — experiments that mainstream researchers are unwilling or unable to do. Echoing Jane Jacobs, I’ve said farmers didn’t invent tractors. That’s not what farmers do, nor could they do it. Likewise, mainstream health researchers, such as medical school professors, are unable to greatly improve their research methods. That’s not what they do, nor could they do it. They have certain methodological skills; they apply them over and over. To understand the limitations of those methods would require a broad understanding of science that few health researchers seem to have. (For example, many health researchers dismiss correlations because “correlation does not equal causation.” In fact, correlations have been extremely important clues to causality.) Big improvements in health research will never come from people who make their living doing health research, just as big improvements in farming have never come from farmers. That’s where QS comes in.

The first QS conference is May 28-29. Tickets are still available.

Personal Science

In the IEEE Spectrum, Paul McFedries, the author of Word Spy, writes about new words generated by new kinds of science made possible by cheap computing.

Perhaps the biggest data set of all is the collection of actions, choices, and preferences that each person performs throughout the day, which is called his or her data exhaust. Using such data for scientific purposes is called citizen science. This is noisy data in that most of it is irrelevant or even misleading, but there are ways to cull signal.

That’s not my understanding of what citizen science means. I’ve seen it used when non-scientists (“citizens”) help professional scientists. The Wikipedia definition is

projects or ongoing program of scientific work in which individual volunteers or networks of volunteers, many of whom may have no specific scientific training, perform or manage research-related tasks such as observation, measurement or computation

Bird-watching, for example.

My self-experimentation is not citizen science. I am not doing it to help a professional scientist nor as part of a project. I do it to help myself — in contrast to professional science, which is a job. Almost all self-experimentation by professional scientists and doctors has been done as part of their job. So let me coin a term that describes what I do: personal science. Science done to help the person doing it.

I believe personal science will grow enormously, for several reasons: 1. Lower cost. The necessary equipment, such as software, costs less and less. I use R, which is free. 2. Greater income. People can afford more stuff. 3. More leisure time. 4. More is known. The more you know, the more effective your research will be. The more you know the better your choice of treatment, experimental design, and measurement and the better your data analysis. 5. More access to what is known. For example, Dennis Mangan discovered via the internet that niacin had cured restless leg syndrome. 6. Professional scientists unable to solve problems. They are crippled by career considerations, poor training, the need to get another grant, desire to show off (projects are too large and too expensive), and a Veblenian dislike of being useful. As a result, problems that professionals can’t solve are solved by amateurs. The best-known example is the invention of blood-glucose self-monitoring by Richard Bernstein, who was not a doctor when he invented it.

“Reading Seth Roberts Puts Me to Sleep”

… is the charming title of this post by Adam Stoffa. Actually, reading me keeps him asleep. Adam read my long self-experimentation paper and came across my discovery that skipping breakfast reduced early awakening. He had early awakening:

I would wake up sometime between 0400 and 0430. Six hours of sleep was not good. This was a problem that needed my attention.

Like me, he was eating breakfast around 7 am and waking up three hours earlier. He ate a big breakfast. He decided to make breakfast later rather than skip it.

I started experimenting with a late breakfast in August. I was traveling through multiple time zones at the time. So I had no idea whether it was working. But by the time I got back to Korea, eating a late breakfast was becoming a habit.

After recovering from my jet lag, I noticed that the experiment was working. Now, I wake up and get out of bed between 0600 and 0615. Sometimes, I still wake up in the middle of the night, but after a quick bathroom break, I’m right back to sleep. I get to work at 0800. After working for an hour, I take a break and eat (e.g. 3 hard boiled eggs, +/- a cup of cashews or macadamia nuts, and a smoothie). This regiment has been working well for eight weeks and shows no signs of weakening.

Yay!

The Buttermind Experiment

In August, at a Quantified Self meeting in San Jose, I told how butter apparently improved my brain function. When I started eating a half-stick of butter every day, I suddenly got faster at arithmetic. During the question period, Greg Biggers of genomera.com proposed a study to see if what I’d found was true for other people.

Eri Gentry, also of genomera.com, organized an experiment to measure the effect of butter and coconut oil on arithmetic speed. Forty-five people signed up. The experiment lasted three weeks (October 23-November 12). On each day of the experiment, the participants took an online arithmetic test that resembled mine.

The participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: Butter, Coconut Oil, or Neither. The three weeks were divided into three one-week phases. During Phase 1 (baseline), the participants ate normally. During Phase 2 (treatment), the Butter participants added 4 tablespoons of butter (half a stick of butter) each day to their usual diet. The Coconut-Oil participants added 4 tablespoons of coconut oil each day to their usual diet. The Neither participants continued to eat normally. During Phase 3 (baseline), all participants ate normally.

After the experiment was finished. Eri reduced the data set to participants who had done at least 10 days of testing. Then she made the data available. I wanted to compute difference scores (Phase 2 MINUS average of Phases 1 and 3) so I eliminated someone who had no Phase 3 data. I also eliminated four days where the treatment was wrong (e.g., in the sequence N N N N N B B N N B, where N = Neither and B = Butter, I eliminated the final Butter day). That left 27 participants and a total of 443 days of data.

Because the scores on individual problems were close to symmetric on a log scale, I worked with log solution times. I computed a mean for each day for each participant and then a mean for each phase for each participant.

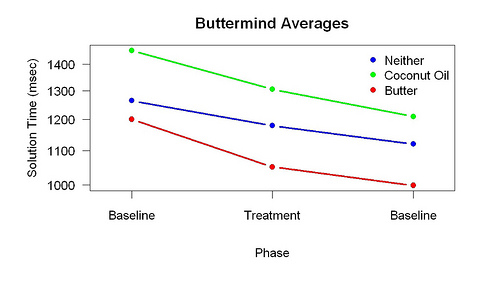

This figure shows the means for each phase and group. The downward slopes show the effect of practice. The separation between the lines shows that individual differences are large. (There was no reliable difference between the three groups during Phase 1.)

This figure shows the means for each phase and group. The downward slopes show the effect of practice. The separation between the lines shows that individual differences are large. (There was no reliable difference between the three groups during Phase 1.)

The point of the baseline/treatment/baseline design is allow for a large practice effect and large individual differences. It allows a treatment effect to be computed for each participant by computing a difference score: Phase 2 MINUS average of Phases 1 and 3. The average of Phases 1 and 3 estimates what the results would be if the treatment made no difference.

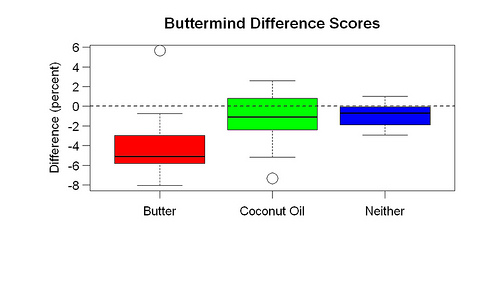

This graph shows the difference scores. There are clear differences by group. A Wilcoxon test comparing the Butter and Neither groups gives one-tailed p = 0.006.

The results support my idea that butter improves brain function. They also suggest that coconut oil does not. In the next post I’ll discuss what else I learned from this experiment.