The first Quantified Self conference will be held in San Jose May 28-29! Robin Barooah and I plan to lead a break-out session about self-experimentation.

Category: self-experimentation

Another Mysterious Mental Improvement (2)

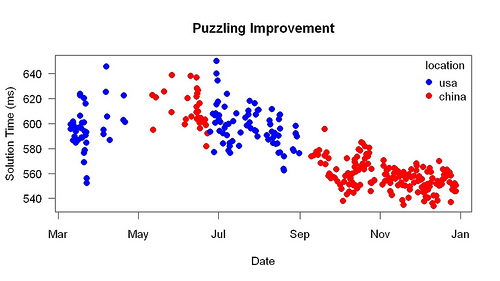

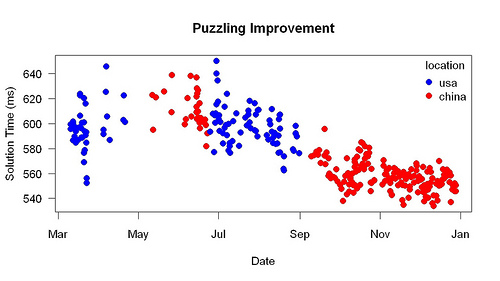

A month ago I posted this graph, which shows how long I needed to type the answer to simple arithmetic problems (7-5, 4*1, 9+0). I tested myself with about 40 problems once or twice per day. Because I’d been doing this for a long time, I no longer improved due to practice. Then, at the end of July 2010, I started improving again.

In September I moved from Berkeley to Beijing. I was worried that in Beijing my scores would get worse. Perhaps I couldn’t get good flaxseed oil or butter. Maybe I would suffer from the air pollution. Maybe I would eat contaminated food. But my scores got better in Beijing.

When I eventually noticed the improvement, I wondered what I was doing differently. Obviously my diet and my life were a lot different in Beijing than Berkeley. Was I eating more walnuts in Beijing? I stopped eating walnuts and my scores didn’t get worse. So it wasn’t walnuts. The most plausible differences I could think of were: 1. Less aerobic exercise in Beijing. 2. Less vitamins in Beijing. 3. Warmer in Beijing. I collected data that implied that shower temperature matters — and I can take warmer showers in Beijing than in Berkeley.

All of these proposed explanations implied that the crucial difference was Berkeley versus Beijing. But the improvement started in Berkeley — around the end of July. That was a problem. Recently I realized there was another possible explanation. In Berkeley I had had an amalgam mercury-containing filling replaced with a non-metallic filling. Not because I had symptoms of mercury poisoning, but because it seemed prudent.

I checked my records to see when I had the filling replaced. It was July 28 — right when the improvement started. To my shock, reduction in mercury exposure is now the most plausible explanation of the improvement. Two tests of this explanation are coming up: 1. When I return to Berkeley, will my reaction times go up? 2. When I have more amalgam fillings replaced, will my reaction times go down?

If it turns out that reduction in mercury exposure is the correct explanation, this will be important. I have an average number of fillings. I’d guess that half of Americans have as many amalgam fillings as I did. And — if the mercury explanation is correct — this arithmetic test is a sensitive measure of mercury poisoning. Over the last few years, before the filling was removed, I’d had six hair tests done, all from the same reputable lab. They showed that my mercury level was moderately high, perhaps 75th percentile. Not very worrisome.

I changed dentists because my old dentist made a terrible mistake: he put a gold filling next to an amalgam one. Putting one metal next to a different one is an elementary mistake. Contact of different metals creates an electric current (as Galvani discovered) and releases mercury. (So although I have a normal number of fillings perhaps I have more mercury exposure.) I stopped going to him for any dental work. The last time I went there for a cleaning, I was given a booklet (“we must give you this”) about the many sorts of dental materials — mercury amalgams plus several new ones. The purpose seems to be to tell people mercury amalgams aren’t dangerous (this was stressed) yet get them to choose other materials in the future — mercury amalgams are just one of several possible choices. The controversy about the safety of mercury amalgams is covered here. Sweden, Denmark, and Norway have banned mercury amalgams. The ban began 2008.

What Global Warming Science Really Says

To see the usual arguments for global warming, look no further than this list, which gives the most popular “skeptic arguments” with rebuttals. The person who made this list presumably read lots of stuff and tried to select the best rebuttal in every case.

That reading led to this:

Skeptic argument: Models are unreliable.

Rebuttal: Models successfully reproduce temperatures since 1900 globally, by land, in the air and the ocean.

Notice what it doesn’t say. It doesn’t say Models have successfully predicted temperatures . . .Â

These models have many adjustable parameters. With enough adjustable parameters, you can reproduce anything. The only reasonable test of a model with many adjustable parameters is how well it predicts.

Hal Pashler and I wrote a paper pointing out that psychologists had been doing something similar for 50 years — passing off models with many adjustable parameters as reliable when in fact they hadn’t been tested — when their ability to predict hadn’t been measured. One explanation of the current global warming scare is that there is something to be afraid of. A more plausible explanation, I believe, is that — again — one group of scientists is passing off complex models with many adjustable parameters as reliable when in fact they haven’t been tested.

Preposterous Health Claims of 2010

Katy Steinmetz, a writer for Time, made a list called “Nutty Health Claims of 2010″ and “2010: The Year in Preposterous Health Claims.” The list of 12 includes:

- omega-3 makes kids smarter

- probiotics that prevent colds and flu

- Dannon’s probiotics as wellness elixir

Preposterous!

Marion Nestle, the New York University nutrition expert, has often said she thinks the health claims made for yogurt are bogus — at least when big companies make them. She recently called Dannon’s claims “a case study of successful marketing”.

I Paid A Bribe

The website I Paid A Bribe is a great great idea. It is enormously promising as a way of reducing corruption. India and China, the two biggest countries in the world, both have immense corruption problems.

I Paid A Bribe is so promising because it takes small bits of anger (mental energy) and aggregates them. Anger causes people to take the time necessary to complain. The aggregated results can be used to: 1. Focus correction. Anti-corruption efforts can start with the biggest offenders. 2. Embarrass offenders. 3. Help measure the effect of anti-corruption measures. Without long term records, those initiatives have great difficulty measuring effectiveness.

It is hard for most people to grasp the corruption of medical science, which connects I Paid a Bribe to what I usually write about. The corruption isn’t exactly on the surface: Only medical school professors take something close to bribes. (The pervasiveness of the problem is shown by the fact that all med schools let them do this or don’t enforce rules against it) The corruption consists of this: Some lines of research are more profitable (e.g., more grant money, more prestige) than other lines of research. That is inevitable. What isn’t inevitable is that this is allowed to obscure honest investigation of which lines of research are the most beneficial. The most visible sign of the corruption is that the Nobel Prize in Medicine is usually given for research that hasn’t helped anyone. The 2009 award for telomere research was an egregious example. Even in China and India, you can find government officials who have helped people.

The anger or fear felt by someone asked to pay a bribe is mental energy. In the case of medical science, the corresponding mental energy is much greater — it is the suffering caused by a condition for which medical science has no cure or a poor cure. Depression, acne, autism, poor sleep, diabetes, obesity . . . the daily suffering caused by these and other health problems is staggering. I believe that self-experimentation is a way of doing something useful with that suffering. When aggregated via the internet, it is a way around the failure of mainstream medicine to deal with these problems.

Via Aleks Jakulin.

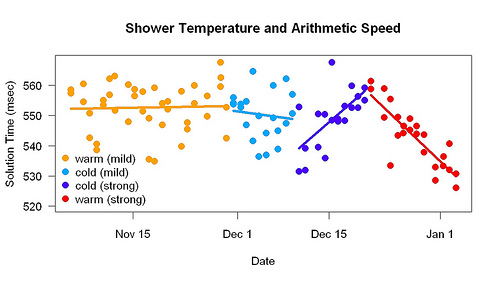

Does Shower Temperature Affect Brain Speed?

In November I learned about benefits of cold showers. So I tried them. I took cold showers that lasted about 5 minutes. I liked the most obvious effect (less sensitivity to cold).

Maybe a bigger “dose” would produce a bigger effect. Maybe the mood improvement cold showers were said to cause would be clearer. So I increased the “dose” in two ways: (a) more water flow (I stopped holes in the shower head) and (b) lower water temperature. After a week or so with the stronger dose, I saw I was gaining weight. It could be the cold showers, I thought. Fat acts as insulation and I couldn’t think of another plausible explanation. So I went from cold showers back to warm showers (48 degrees C.) — this time with greater water flow. My warm showers were 5-10 minutes long.

I began to lose weight, suggesting that the cold water did cause weight gain. More surprising was that my arithmetic speed (time to do simple arithmetic, such as 7-3, 8*4) began to decrease. Here is a graph of the results.

Before the cold showers started my arithmetic speed was roughly constant. The mild cold showers had no clear effect. I had noticed the increase during the strong cold shower phase but hadn’t paid it much attention — I suppose because it seemed implausible. These results, however, are excellent evidence for cause and effect: cold showers made me slower, warm showers made me faster. The arithmetic tests weren’t done soon after the shower. There seems to be some sort of brain-speed adjustment that takes place over ten days or more.

I’ve never heard of anything like this, whereas I’ve heard many times is that cold showers are good. There is one complication, which is that December 3rd I stopped eating walnuts. I believe walnuts are bad for the brain, in contrast to the usual belief. I came to believe that because of results from two students of mine who had tried eating them. Improvement due to no longer eating walnuts would explain why line fitted to the strong cold data starts below where the weak cold line ends. The final days of the strong warm phase may be the same as the weak warm phase when adjusted for the walnut difference.

What explains this? Maybe the weight change. When gaining weight, maybe fat was taken from the blood to be deposited in fat cells, thus lowering the fat content of the blood reaching the brain and thus degrading brain performance. Losing weight, the opposite happens. Eventually the weight loss will stop; this explanation predicts when that happens the warm-water effect will go away.

In a previous post I wondered why I had gotten faster at arithmetic over the previous six months. These data suggest that warm showers may be at least part of the reason. In Berkeley I take baths, not showers.

Do Fermented Foods Shorten Colds?

Alex Chernavsky writes:

I had an interesting experience recently. On Thursday afternoon, I started feeling a little run-down. Then I began to sneeze a lot, and my nose really started to run. I thought I was coming down with a cold. I took an antihistamine and felt a little better. I woke up Friday morning with a mild sore throat (the sneezing/runny nose had stopped). Within a couple of hours, my throat wasn’t sore anymore — and I haven’t felt sick since then. In summary, I believe I had a cold that lasted less than 24 hours. This almost never happens to me. Typically, my colds last at least a week, and usually more (and I usually get two or three colds per year). There is only one other time in my adult life [he’s in his forties] when I can remember having a very short-duration cold.

Maybe it’s the fermented foods I’m eating. After I started reading your blog, I began to brew my own kombucha, and I drink it every day. I also sometimes eat kim chee, fermented dilly beans, fermented salsa, umeboshi plums, and coconut kefir.

This was the first cold he’s gotten since he started eating lots of fermented foods in June. I believe the correlation reflects causation — the fermented foods improve his immune function. The microbes in the food keep the immune system “awake”. I also believe that Alex’s colds would become even less noticeable if he improved his sleep.

Another Mysterious Mental Improvement

This graph shows results from a test of simple arithmetic (e.g., 7-3, 4*8) that I did once or twice most days. Starting in August, I improved about 9% (from 600 to 550 msec/problem).

I don’t know why I got faster. In early September I moved from Berkeley to Beijing. After the move there was an especially sharp decrease. The increase in October was due to an experiment in which I reduced flaxseed oil/day.

I noticed the decrease after I got to China. At first, I thought it was due to a dietary change — perhaps more walnuts. I stopped eating walnuts and the improvement didn’t go away. So it’s not walnuts. It’s not butter; for the first few months in China, I ate the same butter as in Berkeley.

I can’t think of any plausible conventional explanation (e.g., blueberries). Here are the most plausible explanations I can think of:

1. Less aerobic exercise. In China I get much less aerobic exercise than in Berkeley.

2. Less vitamins. In China I consume less vitamins than in Berkeley.

3. Warmer. My Beijing apartment is warmer than my Berkeley apartment. Showers in Beijing are warmer than baths in Berkeley.

In each case the change (e.g., less exercise) could have started in Berkeley. The last one (warmer) is not just the strangest, it’s also the most plausible. Unlike the other two, evidence supports it. Fact 1: When I started heavy-duty cold showers my scores started to get worse. Fact 2: When I stopped cold showers, the scores returned to their pre-cold-shower level. Fact 3: When I moved to China it was very hot, which would explain the sharp decline at that time.

Rich and Poor Students: How to Distinguish

At Tsinghua University, there is a great range of wealth among students. Some are from very rich families, some from very poor. I asked a friend how to distinguish rich students and poor ones.

“At the student store, rich students buy things that cost more than 15 yuan [2 dollars],” she said.

I asked another student the same question.

“By their shoes,” he said, “especially sports shoes.” Poor students wear Chinese brands you’ve never heard of. Rich students wear American brands.

Like my friend’s answer, this surprised me. At the Beijing Zoo, I paid $10 for Nike shoes that cost $100 in America. Yet when visiting America, Chinese people I know have bought Nike shoes, because genuine Nike cost less in America than in China. So the American shoes of the rich students are probably genuine (> $100) and the Chinese-brand shoes of the poor students cost less than $10 ($5?).

Cold Shower Report (2)

After learning that cold showers can raise mood, I started taking cold showers. The mood improvement was hard to notice but it was easy to notice that I became more comfortable in the cold. My apartment seemed warmer.

To increase the effect, I increased the water flow (by unplugging shower-head holes that were clogged) and lowered the water temperature (running the water several minutes before starting the shower). The water was obviously colder and its effects larger. Now the showers did raise my mood, for maybe an hour. It was curious how they were unpleasant for only a second.

After a week or so of the colder showers, it became clear, alas, that my weight was increasing. I gained about 2 pounds. There was no obvious explanation for this other than the cold showers. I hadn’t changed my diet in a big way. I hadn’t changed my activities. And there is plenty of evidence that skin temperature controls body fat. For example, a study of three types of exercise (stationary bike, walking, and swimming) in women found that the women who biked and walked lost weight but the women who swam did not, in spite of equal fitness improvement. So I have stopped the cold showers.