In this interviewer Craig Venter says that sequencing the human genome has had “close to zero” medical benefits so far. I thought this comment was even more interesting:

The human genome project was . . . supposed to be the biggest thing in the history of biological sciences. Billions in government funding for a single project — we had never seen anything like that before in biology. And then a single person comes along and beats scientists who have been working on it for years.

The government-funded people used inferior methods, said Venter:

Initially, Francis Collins and the other people on the Human Genome Project claimed that my methods would never work. When they started to realize that they were wrong, they began personal attacks against me.

The government-funded research was high in quantity (“billions”) but low in quality.

A similar story emerged from the Netflix Prize competition. Netflix had in-house researchers who had tried to do the same thing as the competitors for the prize: predict ratings. The algorithm they’d developed took two weeks to run. According to my friend David Purdy, one of the competitors for the prize managed to compute the same thing in an hour, the same sort of speed-up that Venter is talking about. The in-house research was high in quantity (it had been going on for years) but low in quality.

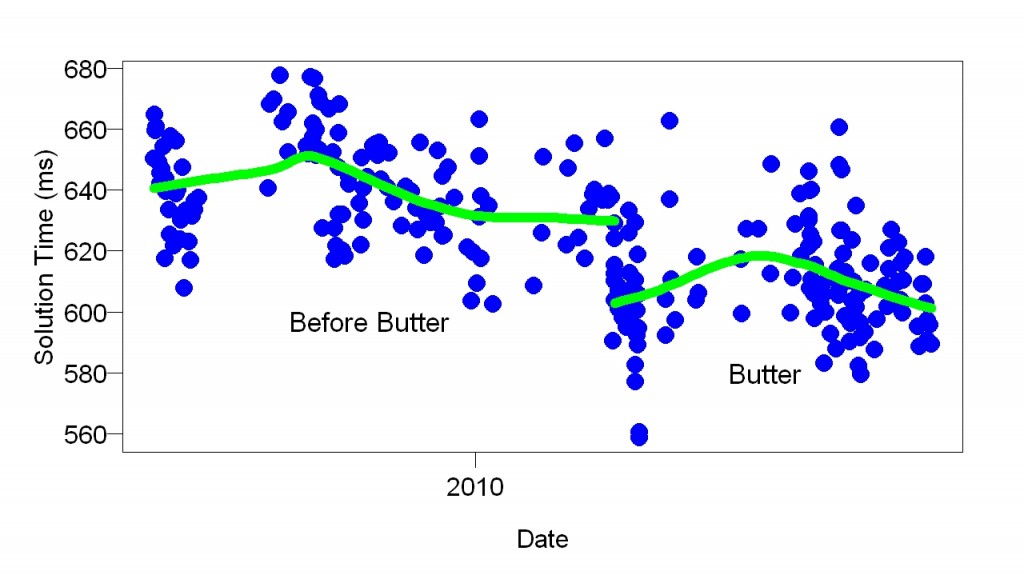

From my point of view, a similar story comes from my self-experimentation. Working alone, with no funding, I found several ways to improve my sleep — avoiding breakfast, standing a lot, standing on one foot, eating pork fat, etc. In contrast, professional sleep researchers have found nothing that has helped me improve my sleep. There are hundreds of sleep researchers and they’ve received hundreds of millions of dollars in funding.

Why such big differences in outcome? I think it has to do with the price of failure. When the government-funded genome researchers used inferior methods, nothing happened. They’d already gotten the grant. In contrast, Venter’s group got nothing until they succeeded. In the case of the Netflix in-house researchers, use of inferior methods cost them nothing; they still got paid. Whereas the prize competitors didn’t get paid unless they won. Use of inferior methods would cause them to lose. In the case of the sleep researchers, lack of practical results cost them nothing. They could still have a successful career. Whereas to me, without practical results I had nothing.

Thanks to Paul Sas.