I have blogged many times about biohacker Tara Grant’s discovery that she slept much better if she took Vitamin D3 in the morning rather than later. Many people reported similar experiences, with a few exceptions. Lots of professional research has studied Vitamin D3 but the researchers appear to have no idea of this effect. They don’t control the time of day that subjects take D3 and don’t measure sleep. If the time of day of Vitamin D3 makes a big difference, measuring Vitamin D3 status via blood levels makes no sense. Quite likely other benefits of Vitamin D3 require taking it at the right time of day. Taking Vitamin D3 at a bad time of day could easily produce the same blood level as taking it at a good time of day.

I too had no idea of the effect that Grant discovered. I had taken Vitamin D3 several times — never in the morning — but after noticing no change stopped. I tested Grant’s discovery by taking Vitamin D3 at 8 or 9 am. First, taking it at 8 am, I gradually increased the dose from 2000 IU to 8000 IU. Then I shifted the time to 9 am. The experiment ended earlier than I would have liked because I had to fly to San Francisco.

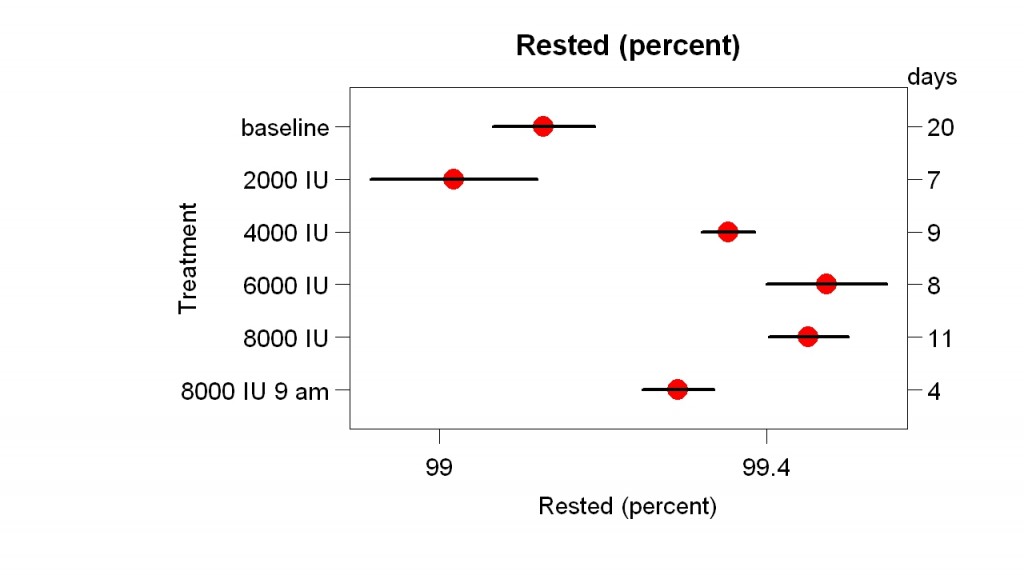

When I woke up in the morning I rated how rested I felt on a 0-100 scale, where 0 = not rested at all and 100 = completely rested. I’d been using this scale for years. Here are the results (means and standard errors):

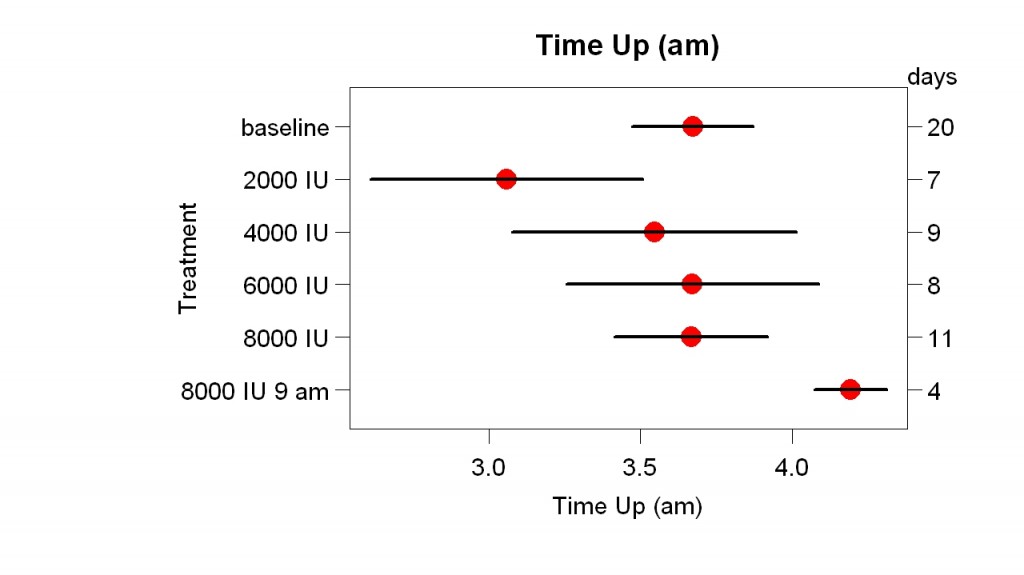

Vitamin D3 had a clear effect, but the necessary dose was more than 2000 IU. If Vitamin D3 acts like sunlight, you might think that taking it in the morning would make me wake up earlier. Here are the results for the time I woke up:

There was no clear effect of dosage on when I got up. Shifting the time from 8 am to 9 am may have had an effect (I wish I had 3 more days at 9 am).

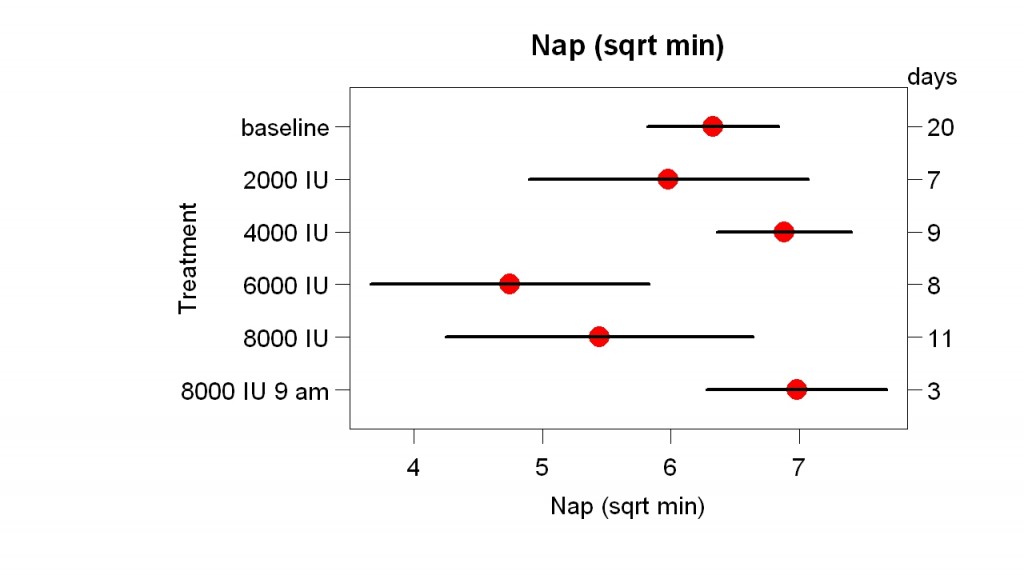

Many people have reported that taking Vitamin D3 in the morning gave them more energy during the day. I usually take a nap in the early afternoon so I measured its effect on the length of those naps:

Maybe my naps were shorter with 6000 and 8000 IU at 8 am. It’s interesting that 4000 IU seemed to be enough to improve how rested how I felt but not enough to shorten my naps.

What do these results add to what we already know? First, the large-enough dose was more than 2000 IU. (A $22 million study of Vitamin D3 is using a dose of 2000 IU.) The dose needed to get more afternoon energy may be more than 4000 IU. Second, careful experimentation and records helped, even though many people found the effect so large it was easy to notice without doing anything special. For example, these results suggest the minimum dose you need to get the effect. Three, these support the value of supplements. Many people say it is better to get necessary nutrients from food rather than supplements. However, supplements allow much better control of dosage and timing and these results suggest that small changes in both can matter. I cannot imagine this effect being discovered with Vitamin D3 in food.

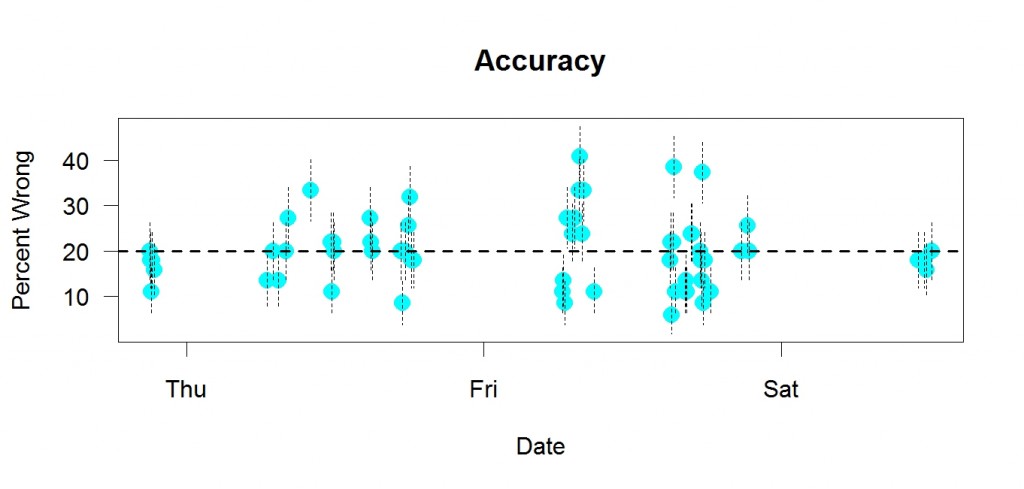

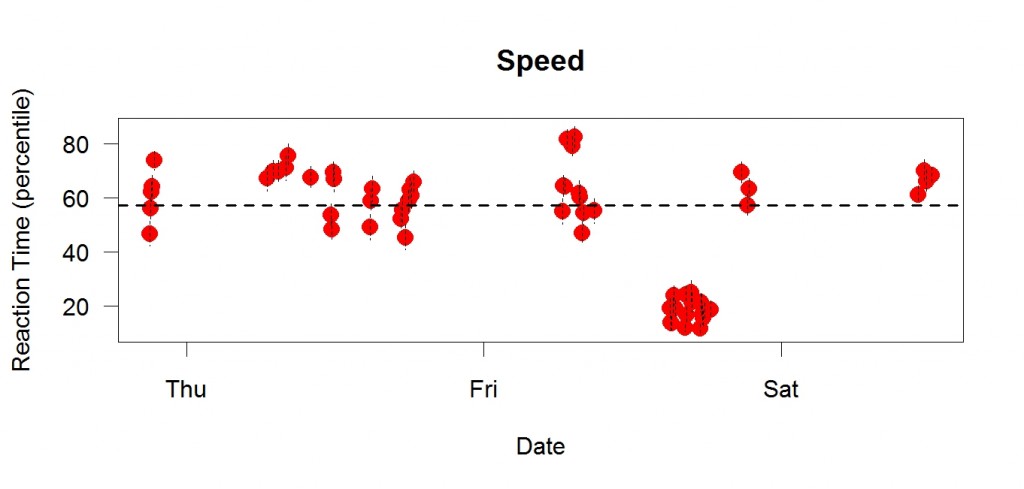

This is me a few days ago. I did a choice reaction time task many times. Each dot is a session with enough trials to supply 32 correct answers.The y axis is in “percentile” units, meaning speed relative to recent performance. If my speed was at the average of recent performance, the percentile would be 50, for example. Higher percentiles = better performance = faster (shorter reaction time). Each point is a mean; the vertical bars are standard errors. The dotted line is the median of the means.

This is me a few days ago. I did a choice reaction time task many times. Each dot is a session with enough trials to supply 32 correct answers.The y axis is in “percentile” units, meaning speed relative to recent performance. If my speed was at the average of recent performance, the percentile would be 50, for example. Higher percentiles = better performance = faster (shorter reaction time). Each point is a mean; the vertical bars are standard errors. The dotted line is the median of the means.