After the striking correlation I described earlier — I ate lot more animal fat than usual and slept longer and had more energy the next day — I started eating much more of what had produced the correlation: pork belly (which is used to make bacon). I couldn’t get uncured pork belly, so I ate bacon. I usually ate it raw. I tried several brands; the only one I liked was from Fatted Calf ($10/pound).

In Beijing I discovered pork belly for sale in every meat department. It is used to make a dish said to be Chairman Mao’s favorite. I bought a soup cooker, an appliance I haven’t seen in America, which made it easy to cook the pork belly. I seemed to sleep better when I had it for lunch.

Finally I did an experiment. I ate pork belly for lunch some days but not others. I ate the pork belly in miso soup, with vegetables. I always ate a whole package of pork belly, which was about 0.7 lb and perhaps 80% fat, 20% meat. On baseline days I ate my usual diet, which was already high-fat by people’s standards. (For example, I ate a lot of whole milk yogurt, a fair amount of nuts, and ordinary amounts of meat.) I tried to alternate baseline and pork-belly days but this wasn’t always possible.

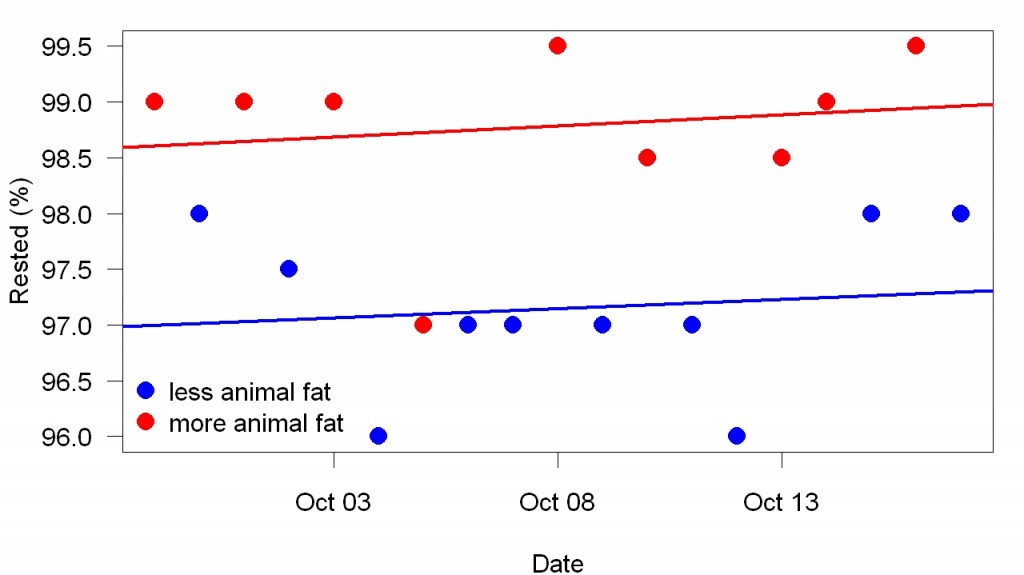

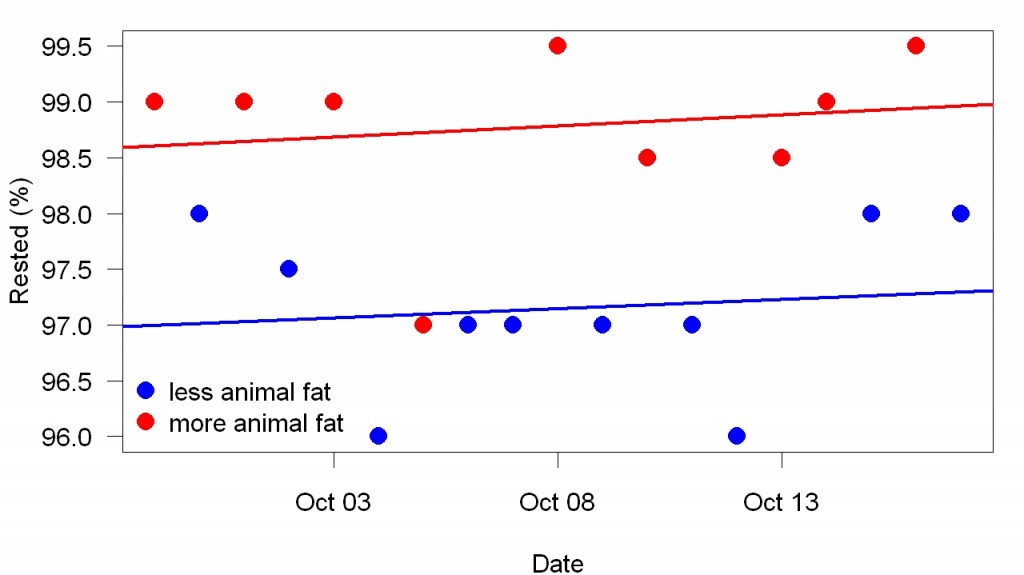

Here are the results on ratings of how rested I felt when I awoke (100% = completely rested = the most rested I have ever felt, 0% = not rested at all).

The lines were fit separately to each set of points (red line to the red points, etc.). The difference is is very consistent (t = 5). Differences in how long I slept were much less clear. I will discuss them in a separate post.

The fascinating thing about this effect isn’t just how clear it is; it’s also how fast it goes on and off (within a day). With most nutrients you’d never see an effect like this. For example, scurvy takes months to develop and a few weeks to recover from. The omega-3 effects I’ve studied have a fast onset but take days to go away.

Sleep is controlled by the brain, of course. The brain is more than half fat, but determinations of how much fat the brain has have measured structural fat. This effect is so fast, both on and especially off, that it must involve circulating fat. Apparently my brain works better when there is a certain amount of animal fat in my blood. This supports Chairman Mao’s idea that pork belly is “brain food” but is a new idea for American intelligentsia. I think the chance that a nutrient that is good for one part of the body is bad for another part is zero — the same as the chance that the electrical appliances you own work best with widely-different currents. The obvious conclusion suggested by this data is that we need plenty of animal fat to be healthy. The only novel element of these lunches was the animal fat. Miso soup with ordinary meat has no effect on my sleep, as far as I know.

I think the science of nutrition proceeds in four steps, repeated over and over for each necessary nutrient: 1. Figure out that we need it. 2. Determine a way to measure how much of it we need. 3. Figure out the optimal amount. 4. Check your answer. With animal fat, conventional nutrition science hasn’t quite reached Step 1. Before this data, I’d say the clearest evidence that we need animal fat is that fat tastes good and long ago we had very little plant fat so it must have been the benefits of animal fat that produced the fat-tastes-good linkage. But conventional nutrition scientists never think this way — never take what we want to eat as meaning anything. And the mere fact that fat tastes good is no help figuring out how much is best.

This data pushes our knowledge toward Step 2. It doesn’t just suggest we need plenty of animal fat for best health, it also makes two methodological points: 1. Animal fat improves brain function. There may be better measures of the improvement than sleep quality. 2. The timing of the improvement — which as far as I know is unprecedented in the study of nutrition — makes it easy to measure.

Yesterday at a Carrefour I watched a pig being cut up. The butcher cut off the skin (with a thick layer of fat) and tossed it into a section of the display of pork for sale. I could buy the part of the pig I valued most for an incredibly low price (about 25 cents/pound). All other pork cost more. That’s how much Chinese shoppers wanted it. No one rushed to buy the newly-cut piece of skin. It reminded me of New York where I tried to buy food past its expiration date, ordinarily considered worthless.