From my omega-3 results I got the idea that our brains may work better or worse without our noticing. I want to track how well my brain works not only to test the effects of different dietary fats (our brain is more than half fat) but also to allow the possibility of discovering new effects, both good and bad.

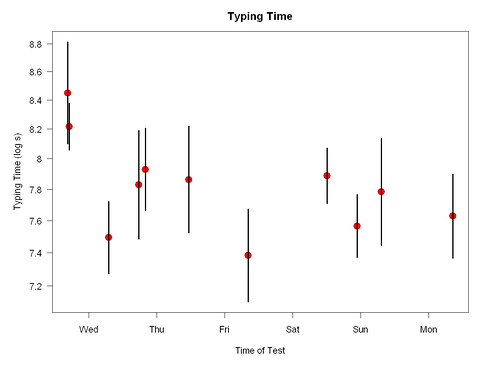

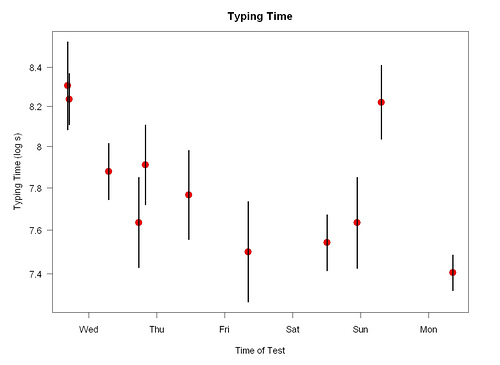

One test I am using is a typing test (early results here). Another is an arithmetic test. I got the idea of using arithmetic from Tim Lundeen. Like him, I found that the speed with which I could do simple arithmetic problems (8+0, 4*3) was sensitive to the amount of omega-3 in my diet.

The arithmetic test involves doing 100 problems separated into 5 blocks of 20 each. There is little time between each problem. I type the last digit in the answer; e.g., if I see 8*8 I type 4. The possible answers are 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, and 0 so that I don’t have to move my fingers off the keys. There is feedback after each block. I aim for 95% correct.

This is my second use of an arithmetic test. The advantages of this one compared to several other tasks I have tried are:

- Portable. Only requires a laptop.

- Well-learned. So I should plateau (reach a steady speed) sooner than with a task I learn from scratch. When my speed is steady it will be easier to compare different conditions — no need to correct for learning.

- Uses eight fingers. Many tasks used by experimental psychologists have just two possible answers (yes/no). With eight possible answers there is less anticipation and less worry about repetitive strain injury.

- No data entry. The task is written in R, the language I use to analyze the data.

- Many measurements per minute. This allows me to correct for problem difficulty and get a standard error for each test session.

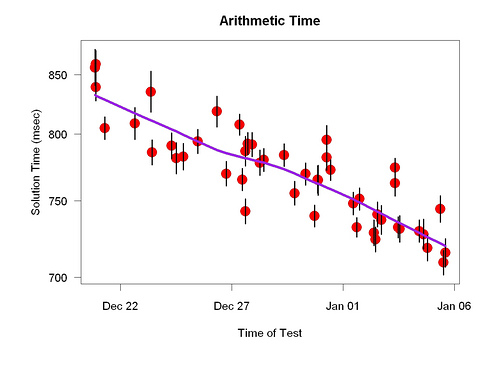

Here are early results.

In the test sessions after January 1, two sets of points are above the line — I was slower than expected, in other words. Both came from test sessions about an hour or so after I woke up. At the time of those sessions I felt fine — not tired, not groggy — and was a little surprised. This is a trivial example of what I am looking for: new environmental effects.

The bigger context of this research is that scientists know a lot about idea testing but almost nothing about idea generation — how to find new ideas worth testing. Maybe this research will teach me something about idea generation.

A talk by Tim Lundeen about related stuff.

By which I mean journalism that involves doing an experiment. In

By which I mean journalism that involves doing an experiment. In